Эта статья требует дополнительных ссылок для проверки . ( январь 2011 г. ) ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить этот шаблон сообщения ) |

Часть серии о |

|---|

| История Франции |

|

| График |

| Портал Франции |

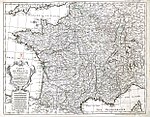

Галлия ( лат . Gallia ) [1] была регионом Западной Европы, впервые описанным римлянами. [2] Он был населен кельтскими племенами, включая нынешнюю Францию , Люксембург , Бельгию , большую часть Швейцарии и некоторые части Северной Италии , Нидерландов и Германии , особенно западный берег Рейна . Он занимал площадь 494 000 км 2 (191 000 кв. Миль). [3] По словам Юлия ЦезаряГаллия была разделена на три части: Галлию Кельтскую , Бельгику и Аквитанию . Археологически галлы были носителями культуры Ла Тен , которая распространилась по всей Галлии, а также на восток до Рэтии , Норикума , Паннонии и юго-западной Германии в течение 5–1 веков до нашей эры. [4] Во 2-м и 1-м веках до нашей эры Галлия попала под власть Рима: Галлия Цизальпина была завоевана в 203 году до нашей эры, а Галлия Нарбонская - в 123 году до нашей эры. После 120 г. до н.э. в Галлию вторглись кимвры и тевтоны., которые, в свою очередь, были побеждены римлянами к 103 г. до н. э. Юлий Цезарь окончательно покорил оставшиеся части Галлии в своих кампаниях 58–51 гг. До н. Э.

Римский контроль над Галлией длился пять веков, пока последнее римское крупное государство , Владение Суассон , не перешло к франкам в 486 году нашей эры. В то время как кельтские галлы утратили свою изначальную идентичность и язык во время поздней античности , объединившись в Галло Римская культура , Галлия оставалась условным названием территории на протяжении всего раннего средневековья , пока она не приобрела новую идентичность как Королевство Капетингов во Франции в период высокого средневековья. Галлия остается названием Франции на современном греческом языке (Γαλλία) и современной латыни.(помимо альтернатив Francia и Francogallia ).

Имя [ редактировать ]

Греческие и латинские имена Галатия (впервые засвидетельствованные Тимеем из Тавромениума в 4 веке до н.э.) и Галлия в конечном итоге произошли от кельтского этнического термина или клана Гал (а) -то- . [5] Галли из кельтика , как сообщалось, называют себя Celtae Цезарем. Эллинистическая народная этимология связала имя галатов (Γαλάται, Galátai ) с якобы «молочно-белой» кожей (γάλα, gála «молоко») галлов. [6] Современные исследователи говорят, что это связано с валлийским галлу ,[7] Корнуолл : галлы , [8] «мощность, сила», [9], что означает «могущественные люди».

Несмотря на внешнее сходство, английский термин Gaul не имеет отношения к латинскому Gallia . Оно происходит от французского Gaule , происходящего от древнефранкского * Walholant (через латинизированную форму * Walula ) [10], буквально «Земля иностранцев / римлян». * Валхо - это рефлекс протогерманского * walhaz , «чужеземец, романизированный человек», экзоним, применяемый говорящими на германском языке по отношению к кельтам и латиноязычным людям без разбора. Это родственно с именами Уэльс , Корнуолл, Валлония и Валахия . [11] Германское w- регулярно переводится как gu- / g- во французском языке (ср. Guerre «война», garder «ward», Guillaume «William»), а исторический дифтонг au является регулярным результатом al перед следующий согласный (ср. cheval ~ chevaux ). Французский Gaule или Gaulle не может быть производным от латинского Gallia , так как g превратилось бы в j до того, как(ср. gamba > jambe ), и дифтонг au будет необъясним; регулярным результатом латинского Gallia является Jaille на французском языке, который встречается в нескольких западных топонимах, таких как La Jaille-Yvon и Saint-Mars-la-Jaille . [12] [13] Протогерманский * walha происходит от названия Volcae . [14]

Также не связано, несмотря на внешнее сходство, имя Гаэль . [16] ирландское слово желчного были первоначально означать «Галлий», то есть житель Галлии, но его смысл было позже расширен до «иностранца», чтобы описать викинг , а затем еще на норманнах . [17] В дихотомические слова Гаэль и желчный иногда используются вместе для контраста, например , в книге 12-го века Cogad Gáedel вновь Gallaib .

В качестве прилагательных у английского есть два варианта: галльский и галльский . Эти два прилагательных используются как синонимы, как «относящиеся к Галлии или галлам», хотя кельтский язык или языки, на которых говорят в Галлии, в основном известны как галльский .

История [ править ]

Доримская Галлия [ править ]

Существует мало письменных сведений о народах, населявших регионы Галлии, за исключением того, что можно почерпнуть из монет. Следовательно, ранняя история галлов - это преимущественно работа в области археологии, и отношения между их материальной культурой , генетическими отношениями (изучению которых в последние годы способствовала область археогенетики ) и лингвистическими разделениями редко совпадают.

До быстрого распространения культуры Ла Тена в V-IV веках до нашей эры территория восточной и южной Франции уже участвовала в культуре Урнфилдов позднего бронзового века (примерно 12-8 века до н.э.), из которой началась ранняя обработка железа Развивается культура Гальштата (7-6 вв. До н.э.). К 500 г. до н. Э. Влияние Гальштата ощутимо на большей части территории Франции (за исключением Альп и крайнего северо-запада).

Из этого гальштатского фона, в VII и VI веках до нашей эры, предположительно представляя раннюю форму континентальной кельтской культуры, возникла культура Ла Тен, предположительно под средиземноморским влиянием греческой , финикийской и этрусской цивилизаций , распространившихся в ряде ранних Центры вдоль Сены , Среднего Рейна и верхней Эльбы . К концу V века до нашей эры влияние Ла Тена быстро распространяется по всей территории Галлии. Культура латенского разработана и процветала в конце железного века (от 450 г. до н.э. до римского завоевания в до н.э. 1) в Франции ,Швейцария , Италия , Австрия , юго-запад Германии , Чехия , Моравия , Словакия и Венгрия . Дальше на север простиралась современная доримская культура железного века северной Германии и Скандинавии .

Основным источником материалов о кельтах Галлии был Посейдоний из Апамеи , чьи труды цитировали Тимаген , Юлий Цезарь , сицилийский грек Диодор Сицилийский и греческий географ Страбон . [18]

В 4-м и начале 3-го веков до нашей эры конфедерации галльских кланов расширились далеко за пределы территории, которая впоследствии стала Римской Галлией (что определяет использование термина «Галлия» сегодня), в Паннонию, Иллирию, северную Италию, Трансильванию и даже Малую Азию . Ко II веку до нашей эры римляне описали Галлию Трансальпинскую в отличие от Галлии Цизальпинской . В своих галльских войнах , Юлий Цезарь различает среди трех этнических групп в Галлии: Belgae на севере (примерно между Рейном и Сеной ), то Celtae в центре и в Арморики и аквитанна юго-западе, юго-восток уже колонизирован римлянами. Хотя некоторые ученые полагают, что белги к югу от Соммы были смесью кельтских и германских элементов, их этническая принадлежность окончательно не решена. Одна из причин - политическое вмешательство во французскую историческую интерпретацию в XIX веке.

Помимо галлов, в Галлии жили и другие народы, такие как греки и финикийцы , которые основали форпосты, такие как Массилия (современный Марсель ), вдоль побережья Средиземного моря. [19] Кроме того, вдоль юго-восточного побережья Средиземного моря лигуры слились с кельтами, образовав кельто- лигурийскую культуру.

Первоначальный контакт с Римом [ править ]

Во 2 веке до н.э. Средиземноморская Галлия имела разветвленную городскую структуру и процветала. Археологам известны города в северной Галлии, включая битуригианскую столицу Аварикум ( Бурж ), Сенабум ( Орлеан ), Аутрикум ( Шартр ) и раскопки Бибракте недалеко от Отена в Соне-и-Луаре, а также ряд фортов на холмах (или oppida ) использовались во время войны. Процветание Средиземноморской Галлии побудило Рим откликнуться на мольбы о помощи от жителей Массилии , которые оказались под атакой коалиции лигуров и галлов. [20]Римляне вторглись в Галлию в 154 г. до н.э. и снова в 125 г. до н.э. [20] В то время как в первый раз они приходили и уходили, во второй они остались. [21] В 122 г. до н.э. Домиций Агенобарб сумел победить аллоброгов (союзников Саллувий ), в то время как в следующем году Квинт Фабий Максим «уничтожил» армию арвернов во главе с их королем Битуитом , который пришел на помощь Аллоброги. [21] Рим позволил Массилии сохранить свои земли, но добавил к своим территориям земли побежденных племен. [21]В результате этих завоеваний Рим теперь контролировал территорию, простирающуюся от Пиренеев до нижнего течения реки Рона и на востоке до долины Роны до Женевского озера . [22] К 121 г. до н.э. римляне завоевали Средиземноморский регион под названием Провинция (позже названный Галлией Нарбоненсис ). Это завоевание нарушило господство галльских арвернов .

Завоевание Римом [ править ]

Римский проконсул и генерал Юлий Цезарь двинул свою армию в Галлию в 58 г. до н.э., якобы для помощи галльским союзникам Рима против мигрирующих гельветов. С помощью различных галльских кланов (например, эдуев) ему удалось завоевать почти всю Галлию. Хотя их армия была столь же сильна, как и у римлян, внутреннее разделение между галльскими племенами гарантировало легкую победу Цезарю, а попытка Верцингеторикса объединить галлов против римского вторжения была предпринята слишком поздно. [23] [24]Юлий Цезарь был остановлен Верцингеториксом при осаде Герговии, укрепленного города в центре Галлии. Союзы Цезаря со многими галльскими кланами распались. Даже эдуи, их самые верные сторонники, присоединились к арвернам, но всегда верные Реми (наиболее известный своей кавалерией) и Лингонес послали войска, чтобы поддержать Цезаря. Германцы из Убии также прислали конницу, которую Цезарь снабдил лошадьми Реми. Цезарь захватил Верцингеторикс в битве при Алезии , которая положила конец сопротивлению галлов Риму.

Целый миллион человек (вероятно, каждый пятый галл) погиб, еще миллион был порабощен , [25] 300 кланов были порабощены и 800 городов были разрушены во время Галльских войн . [26] Все население города Аварикум (Бурж) (всего 40 000 человек) было убито. [27] Перед походом Юлия Цезаря против гельветов (современная Швейцария ), гельветов насчитывалось 263 000 человек, но впоследствии осталось только 100 000, большинство из которых Цезарь взял в рабство . [28]

Римская Галлия [ править ]

After Gaul was absorbed as Gallia, a set of Roman provinces, its inhabitants gradually adopted aspects of Roman culture and assimilated, resulting in the distinct Gallo-Roman culture.[29] Citizenship was granted to all in 212 by the Constitutio Antoniniana. From the third to 5th centuries, Gaul was exposed to raids by the Franks. The Gallic Empire, consisting of the provinces of Gaul, Britannia, and Hispania, including the peaceful Baetica in the south, broke away from Rome from 260 to 273. In addition to the large number of natives, Gallia also became home to some Roman citizens from elsewhere and also in-migrating Germanic and Scythian tribes such as the Alans.[30]

The religious practices of inhabitants became a combination of Roman and Celtic practice, with Celtic deities such as Cobannus and Epona subjected to interpretatio romana.[31][32] The imperial cult and Eastern mystery religions also gained a following. Eventually, after it became the official religion of the Empire and paganism became suppressed, Christianity won out in the twilight days of the Western Roman Empire (while the Christianized Eastern Roman Empire lasted another thousand years, until the invasion of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453); a small but notable Jewish presence also became established.

The Gaulish language is thought to have survived into the 6th century in France, despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture.[33] The last record of spoken Gaulish deemed to be plausibly credible[33] concerned the destruction by Christians of a pagan shrine in Auvergne "called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue".[34] Coexisting with Latin, Gaulish helped shape the Vulgar Latin dialects that developed into French.[35][36][37][38][39]

The Vulgar Latin in the region of Gallia took on a distinctly local character, some of which is attested in graffiti,[39] which evolved into the Gallo-Romance dialects which include French and its closest relatives. The influence of substrate languages may be seen in graffiti showing sound changes that matched changes that had earlier occurred in the indigenous languages, especially Gaulish.[39] The Vulgar Latin in the north of Gaul evolved into the langues d'oil and Franco-Provencal, while the dialects in the south evolved into the modern Occitan and Catalan tongues. Other languages held to be "Gallo-Romance" include the Gallo-Italic languages and the Rhaeto-Romance languages.

Frankish Gaul[edit]

Following Frankish victories at Soissons (AD 486), Vouillé (AD 507) and Autun (AD 532), Gaul (except for Brittany and Septimania) came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of France. Gallo-Roman culture, the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire, persisted particularly in the areas of Gallia Narbonensis that developed into Occitania, Gallia Cisalpina and to a lesser degree, Aquitania. The formerly Romanized north of Gaul, once it had been occupied by the Franks, would develop into Merovingian culture instead. Roman life, centered on the public events and cultural responsibilities of urban life in the res publica and the sometimes luxurious life of the self-sufficient rural villa system, took longer to collapse in the Gallo-Roman regions, where the Visigoths largely inherited the status quo in the early 5th century. Gallo-Roman language persisted in the northeast into the Silva Carbonaria that formed an effective cultural barrier, with the Franks to the north and east, and in the northwest to the lower valley of the Loire, where Gallo-Roman culture interfaced with Frankish culture in a city like Tours and in the person of that Gallo-Roman bishop confronted with Merovingian royals, Gregory of Tours.

Massalia (modern Marseille) silver coin with Greek legend, 5th–1st century BC.

Gold coins of the Gaul Parisii, 1st century BC, (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris).

Roman silver Denarius with the head of captive Gaul 48 BC, following the campaigns of Julius Caesar.

Gauls[edit]

Social structure, indigenous nation and clans[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Druids were not the only political force in Gaul, however, and the early political system was complex, if ultimately fatal to the society as a whole. The fundamental unit of Gallic politics was the clan, which itself consisted of one or more of what Caesar called pagi. Each clan had a council of elders, and initially a king. Later, the executive was an annually-elected magistrate. Among the Aedui, a clan of Gaul, the executive held the title of Vergobret, a position much like a king, but his powers were held in check by rules laid down by the council.

The regional ethnic groups, or pagi as the Romans called them (singular: pagus; the French word pays, "region" [a more accurate translation is 'country'], comes from this term), were organized into larger multi-clan groups, which the Romans called civitates. These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place—with slight changes—until the French Revolution.

Although the individual clans were moderately stable political entities, Gaul as a whole tended to be politically divided, there being virtually no unity among the various clans. Only during particularly trying times, such as the invasion of Caesar, could the Gauls unite under a single leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, however, the faction lines were clear.

The Romans divided Gaul broadly into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean), and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "long haired Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gallia Comata into three broad groups: the Aquitani; Galli (who in their own language were called Celtae); and Belgae. In the modern sense, Gaulish peoples are defined linguistically, as speakers of dialects of the Gaulish language. While the Aquitani were probably Vascons, the Belgae would thus probably be a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements.

Julius Caesar, in his book, The Gallic Wars, comments:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in our Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws. The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the Marne and the Seine separate them from the Belgae. Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilization and refinement of [our] Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germans, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war; for which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valor, as they contend with the Germans in almost daily battles, when they either repel them from their own territories, or themselves wage war on their frontiers. One part of these, which it has been said that the Gauls occupy, takes its beginning at the river Rhone; it is bounded by the river Garonne, the ocean, and the territories of the Belgae; it borders, too, on the side of the Sequani and the Helvetii, upon the river Rhine, and stretches toward the north. The Belgae rises from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the river Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun. Aquitania extends from the river Garonne to the Pyrenaean mountains and to that part of the ocean which is near Spain: it looks between the setting of the sun, and the north star. .[40]

Religion[edit]

The Gauls practiced a form of animism, ascribing human characteristics to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features and granting them a quasi-divine status. Also, worship of animals was not uncommon; the animal most sacred to the Gauls was the boar[41] which can be found on many Gallic military standards, much like the Roman eagle.

Their system of gods and goddesses was loose, there being certain deities which virtually every Gallic person worshipped, as well as clan and household gods. Many of the major gods were related to Greek gods; the primary god worshipped at the time of the arrival of Caesar was Teutates, the Gallic equivalent of Mercury. The "ancestor god" of the Gauls was identified by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico with the Roman god Dis Pater.[42]

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of Gallic religion is the practice of the Druids. The druids presided over human or animal sacrifices that were made in wooded groves or crude temples. They also appear to have held the responsibility for preserving the annual agricultural calendar and instigating seasonal festivals which corresponded to key points of the lunar-solar calendar. The religious practices of druids were syncretic and borrowed from earlier pagan traditions, with probably indo-European roots. Julius Caesar mentions in his Gallic Wars that those Celts who wanted to make a close study of druidism went to Britain to do so. In a little over a century later, Gnaeus Julius Agricola mentions Roman armies attacking a large druid sanctuary in Anglesey in Wales. There is no certainty concerning the origin of the druids, but it is clear that they vehemently guarded the secrets of their order and held sway over the people of Gaul. Indeed, they claimed the right to determine questions of war and peace, and thereby held an "international" status. In addition, the Druids monitored the religion of ordinary Gauls and were in charge of educating the aristocracy. They also practiced a form of excommunication from the assembly of worshippers, which in ancient Gaul meant a separation from secular society as well. Thus the Druids were an important part of Gallic society. The nearly complete and mysterious disappearance of the Celtic language from most of the territorial lands of ancient Gaul, with the exception of Brittany, can be attributed to the fact that Celtic druids refused to allow the Celtic oral literature or traditional wisdom to be committed to the written letter.[43]

See also[edit]

- Ambiorix

- Asterix—a French comic about Gaul and Rome, mainly set in 50 BC

- Bog body

- Braccae—trousers, typical Gallic dress

- Cisalpine Gaul

- Galatia

- Lugdunum

- Roman Republic

- Roman villas in northwestern Gaul

References[edit]

- ^ English: /ˈɡæliə/

- ^ Polybius: Histories

- ^ Arrowsmith, Aaron (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School. Hansard London 1832. p. 50. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

gallia .

- ^ Bisdent, Bisdent (28 April 2011). "Gaul". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Birkhan 1997, p. 48.

- ^ "The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville" p. 198 Cambridge University Press 2006 Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof.

- ^ "gallu". Google Translate. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Howlsedhes Services. "Gerlyver Sempel". Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions Errance, 1994, p. 194.

- ^ Ekblom, R., "Die Herkunft des Namens La Gaule" in: Studia Neophilologica, Uppsala, XV, 1942-43, nos. 1-2, p. 291-301.

- ^ Sjögren, Albert, Le nom de "Gaule", in Studia Neophilologica, Vol. 11 (1938/39) pp. 210–214.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (OUP 1966), p. 391.

- ^ Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique (Larousse 1990), p. 336.

- ^ Koch 2006, p. 532.

- ^ Koch 2006, pp. 775–776.

- ^ Gael is derived from Old Irish Goidel (borrowed, in turn, in the 7th century AD from Primitive Welsh Guoidel—spelled Gwyddel in Middle Welsh and Modern Welsh—likely derived from a Brittonic root *Wēdelos meaning literally "forest person, wild man")[15]

- ^ Linehan, Peter; Janet L. Nelson (2003). The Medieval World. 10. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-415-30234-0.

- ^ Berresford Ellis, Peter (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- ^ Dietler, Michael (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. Berkeley, CA.

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2014, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Drinkwater 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 6. "[...] the most important outcome of this series of campaigns was the direct annexation by Rome of a huge area extending from the Pyrenees to the lower Rhône, and up the Rhône valley to Lake Geneva."

- ^ "France: The Roman conquest". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix’s Great Rebellion of 52 bc had notable successes.

- ^ "Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

Indeed, the Gallic cavalry was probably superior to the Roman, horseman for horseman. Rome’s military superiority lay in its mastery of strategy, tactics, discipline, and military engineering. In Gaul, Rome also had the advantage of being able to deal separately with dozens of relatively small, independent, and uncooperative states. Caesar conquered these piecemeal, and the concerted attempt made by a number of them in 52 BC to shake off the Roman yoke came too late.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar 22.

- ^ Tibbetts, Jann (2016-07-30). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789385505669.

- ^ Seindal, René (28 August 2003). "Julius Caesar, Romans [The Conquest of Gaul - part 4 of 11] (Photo Archive)". Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Serghidou, Anastasia (2007). Fear of slaves, fear of enslavement in the ancient Mediterranean. Besançon: Presses Univ. Franche-Comté. p. 50. ISBN 978-2848671697. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ A recent survey is G. Woolf, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge University Press) 1998.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481-751. U of Minnesota Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780816657001.

- ^ Pollini, J. (2002). Gallo-Roman Bronzes and the Process of Romanization: The Cobannus Hoard. Monumenta Graeca et Romana. 9. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Oaks, L.S. (1986). "The goddess Epona: concepts of sovereignty in a changing landscape". Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire.

- ^ a b Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- ^ Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- ^ Henri Guiter, "Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania", in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- ^ Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- ^ Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004). Dictionnaire Français-Gaulois. Paris: La Différence. p. 26.

- ^ Matasovic, Ranko (2007). "Insular Celtic as a Language Area". Papers from the Workship within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies. The Celtic Languages in Contact: 106.

- ^ a b c Adams, J. N. (2007). "Chapter V -- Regionalisms in provincial texts: Gaul". The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge. p. 279–289. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482977. ISBN 9780511482977.

- ^ Caesar, Julius; McDevitte, W. A.; Bohn, W. S., trans (1869). The Gallic Wars. New York: Harper. p. 9. ISBN 978-1604597622. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ MacCulloch, John Arnott (1911). The Religion of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh: Clark. p. 22. ISBN 978-1508518518. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Warner, Marina; Burn, Lucilla (2003). World of Myths, Vol. 1. London: British Museum. p. 382. ISBN 978-0714127835. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Kendrick, Thomas D. (1966). The Druids: A study in Keltic prehistory (1966 ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 78.

Sources[edit]

- Birkhan, H. (1997). Die Kelten. Vienna.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2014) [1983]. "Conquest and Pacification". Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC-AD 260. Routledge Revivals. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317750741.

- Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Gaul. |