Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.[2]

The largest driver of warming is the emission of greenhouse gases, of which more than 90% are carbon dioxide (CO

2) and methane.[3] Fossil fuel burning (coal, oil, and natural gas) for energy consumption is the main source of these emissions, with additional contributions from agriculture, deforestation, and manufacturing.[4] The human cause of climate change is not disputed by any scientific body of national or international standing.[5] Temperature rise is accelerated or tempered by climate feedbacks, such as loss of sunlight-reflecting snow and ice cover, increased water vapour (a greenhouse gas itself), and changes to land and ocean carbon sinks.

Temperature rise on land is about twice the global average increase, leading to desert expansion and more common heat waves and wildfires.[6] Temperature rise is also amplified in the Arctic, where it has contributed to melting permafrost, glacial retreat and sea ice loss.[7] Warmer temperatures are increasing rates of evaporation, causing more intense storms and weather extremes.[8] Impacts on ecosystems include the relocation or extinction of many species as their environment changes, most immediately in coral reefs, mountains, and the Arctic.[9] Climate change threatens people with food insecurity, water scarcity, flooding, infectious diseases, extreme heat, economic losses, and displacement. These impacts have led the World Health Organization to call climate change the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.[10] Even if efforts to minimize future warming are successful, some effects will continue for centuries, including rising sea levels, rising ocean temperatures, and ocean acidification.[11]

| Some impacts of climate change |

|

Many of these impacts are already felt at the current level of warming, which is about 1.2 °C (2.2 °F).[13] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has issued a series of reports that project significant increases in these impacts as warming continues to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) and beyond.[14] Additional warming also increases the risk of triggering critical thresholds called tipping points.[15] Responding to climate change involves mitigation and adaptation.[16] Mitigation – limiting climate change – consists of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and removing them from the atmosphere;[16] methods include the development and deployment of low-carbon energy sources such as wind and solar, a phase-out of coal, enhanced energy efficiency, reforestation, and forest preservation. Adaptation consists of adjusting to actual or expected climate,[16] such as through improved coastline protection, better disaster management, assisted colonization, and the development of more resistant crops. Adaptation alone cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.[17]

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nations collectively agreed to keep warming "well under 2.0 °C (3.6 °F)" through mitigation efforts. However, with pledges made under the Agreement, global warming would still reach about 2.8 °C (5.0 °F) by the end of the century.[18] Limiting warming to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) would require halving emissions by 2030 and achieving near-zero emissions by 2050.[19]

Terminology

The term "global warming" is not new. As early as the 1930s, scientists were concerned that "increased carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuel could cause global warming, possibly to the point of eventually melting the ice caps and flooding coastal cities."[20] Before the 1980s, when it was unclear whether warming by greenhouse gases would dominate aerosol-induced cooling, scientists often used the term inadvertent climate modification to refer to humankind's impact on the climate. In the 1980s, the terms global warming and climate change were popularized, the former referring only to increased surface warming, while the latter describes the full effect of greenhouse gases on the climate.[21] Global warming became the most popular term after NASA climate scientist James Hansen used it in his 1988 testimony in the U.S. Senate.[22] In the 2000s, the term climate change increased in popularity.[23] Global warming usually refers to human-induced warming of the Earth system, whereas climate change can refer to natural as well as anthropogenic change.[24] The two terms are often used interchangeably.[25]

Various scientists, politicians and media figures have adopted the terms climate crisis or climate emergency to talk about climate change, while using global heating instead of global warming.[26] The policy editor-in-chief of The Guardian explained that they included this language in their editorial guidelines "to ensure that we are being scientifically precise, while also communicating clearly with readers on this very important issue".[27] Oxford Dictionary chose climate emergency as its word of the year in 2019 and defines the term as "a situation in which urgent action is required to reduce or halt climate change and avoid potentially irreversible environmental damage resulting from it".[28]

Observed temperature rise

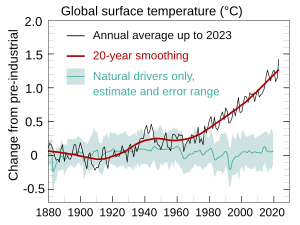

Multiple independently produced instrumental datasets show that the climate system is warming,[31] with the 2009–2018 decade being 0.93 ± 0.07 °C (1.67 ± 0.13 °F) warmer than the pre-industrial baseline (1850–1900).[32] Currently, surface temperatures are rising by about 0.2 °C (0.36 °F) per decade,[33] with 2020 reaching a temperature of 1.2 °C (2.2 °F) above pre-industrial.[13] Since 1950, the number of cold days and nights has decreased, and the number of warm days and nights has increased.[34]

There was little net warming between the 18th century and the mid-19th century. Climate proxies, sources of climate information from natural archives such as trees and ice cores, show that natural variations offset the early effects of the Industrial Revolution.[35] Thermometer records began to provide global coverage around 1850.[36] Historical patterns of warming and cooling, like the Medieval Climate Anomaly and the Little Ice Age, did not occur at the same time across different regions, but temperatures may have reached as high as those of the late-20th century in a limited set of regions.[37] There have been prehistorical episodes of global warming, such as the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum.[38] However, the modern observed rise in temperature and CO

2 concentrations has been so rapid that even abrupt geophysical events that took place in Earth's history do not approach current rates.[39]

Evidence of warming from air temperature measurements are reinforced with a wide range of other observations.[40] There has been an increase in the frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation, melting of snow and land ice, and increased atmospheric humidity.[41] Flora and fauna are also behaving in a manner consistent with warming; for instance, plants are flowering earlier in spring.[42] Another key indicator is the cooling of the upper atmosphere, which demonstrates that greenhouse gases are trapping heat near the Earth's surface and preventing it from radiating into space.[43]

While locations of warming vary, the patterns are independent of where greenhouse gases are emitted, because the gases persist long enough to diffuse across the planet. Since the pre-industrial period, global average land temperatures have increased almost twice as fast as global average surface temperatures.[44] This is because of the larger heat capacity of oceans, and because oceans lose more heat by evaporation.[45] Over 90% of the additional energy in the climate system over the last 50 years has been stored in the ocean, with the remainder warming the atmosphere, melting ice, and warming the continents.[46][47]

The Northern Hemisphere and the North Pole have warmed much faster than the South Pole and Southern Hemisphere. The Northern Hemisphere not only has much more land, but also more seasonal snow cover and sea ice, because of how the land masses are arranged around the Arctic Ocean. As these surfaces flip from reflecting a lot of light to being dark after the ice has melted, they start absorbing more heat.[48] Localized black carbon deposits on snow and ice also contribute to Arctic warming.[49] Arctic temperatures have increased and are predicted to continue to increase during this century at over twice the rate of the rest of the world.[50] Melting of glaciers and ice sheets in the Arctic disrupts ocean circulation, including a weakened Gulf Stream, further changing the climate.[51]

Drivers of recent temperature rise

The climate system experiences various cycles on its own which can last for years (such as the El Niño–Southern Oscillation), decades or even centuries.[52] Other changes are caused by an imbalance of energy that is "external" to the climate system, but not always external to the Earth.[53] Examples of external forcings include changes in the composition of the atmosphere (e.g. increased concentrations of greenhouse gases), solar luminosity, volcanic eruptions, and variations in the Earth's orbit around the Sun.[54]

To determine the human contribution to climate change, known internal climate variability and natural external forcings need to be ruled out. A key approach is to determine unique "fingerprints" for all potential causes, then compare these fingerprints with observed patterns of climate change.[55] For example, solar forcing can be ruled out as a major cause because its fingerprint is warming in the entire atmosphere, and only the lower atmosphere has warmed, as expected from greenhouse gases (which trap heat energy radiating from the surface).[56] Attribution of recent climate change shows that the primary driver is elevated greenhouse gases, but that aerosols also have a strong effect.[57]

Greenhouse gases

2 concentrations over the last 800,000 years as measured from ice cores (blue/green) and directly (black)

The Earth absorbs sunlight, then radiates it as heat. Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere absorb and reemit infrared radiation, slowing the rate at which it can pass through the atmosphere and escape into space.[58] Before the Industrial Revolution, naturally-occurring amounts of greenhouse gases caused the air near the surface to be about 33 °C (59 °F) warmer than it would have been in their absence.[59][60] While water vapour (~50%) and clouds (~25%) are the biggest contributors to the greenhouse effect, they increase as a function of temperature and are therefore considered feedbacks. On the other hand, concentrations of gases such as CO

2 (~20%), tropospheric ozone,[61] CFCs and nitrous oxide are not temperature-dependent, and are therefor considered external forcings.[62]

Human activity since the Industrial Revolution, mainly extracting and burning fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas),[63] has increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, resulting in a radiative imbalance. In 2018, the concentrations of CO

2 and methane had increased by about 45% and 160%, respectively, since 1750.[64] These CO

2 levels are much higher than they have been at any time during the last 800,000 years, the period for which reliable data have been collected from air trapped in ice cores.[65] Less direct geological evidence indicates that CO

2 values have not been this high for millions of years.[66]

2 since 1880 have been caused by different sources ramping up one after another.

Global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in 2018, excluding those from land use change, were equivalent to 52 billion tonnes of CO

2. Of these emissions, 72% was actual CO

2, 19% was methane, 6% was nitrous oxide, and 3% was fluorinated gases.[67] CO

2 emissions primarily come from burning fossil fuels to provide energy for transport, manufacturing, heating, and electricity.[68] Additional CO

2 emissions come from deforestation and industrial processes, which include the CO

2 released by the chemical reactions for making cement, steel, aluminum, and fertilizer.[69] Methane emissions come from livestock, manure, rice cultivation, landfills, wastewater, coal mining, as well as oil and gas extraction.[70] Nitrous oxide emissions largely come from the microbial decomposition of inorganic and organic fertilizer.[71] From a production standpoint, the primary sources of global greenhouse gas emissions are estimated as: electricity and heat (25%), agriculture and forestry (24%), industry and manufacturing (21%), transport (14%), and buildings (6%).[72]

Despite the contribution of deforestation to greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth's land surface, particularly its forests, remain a significant carbon sink for CO

2. Natural processes, such as carbon fixation in the soil and photosynthesis, more than offset the greenhouse gas contributions from deforestation. The land-surface sink is estimated to remove about 29% of annual global CO

2 emissions.[73] The ocean also serves as a significant carbon sink via a two-step process. First, CO

2 dissolves in the surface water. Afterwards, the ocean's overturning circulation distributes it deep into the ocean's interior, where it accumulates over time as part of the carbon cycle. Over the last two decades, the world's oceans have absorbed 20 to 30% of emitted CO

2.[74]

Aerosols and clouds

Air pollution, in the form of aerosols, not only puts a large burden on human health, but also affects the climate on a large scale.[75] From 1961 to 1990, a gradual reduction in the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface was observed, a phenomenon popularly known as global dimming,[76] typically attributed to aerosols from biofuel and fossil fuel burning.[77] Aerosol removal by precipitation gives tropospheric aerosols an atmospheric lifetime of only about a week, while stratospheric aerosols can remain in the atmosphere for a few years.[78] Globally, aerosols have been declining since 1990, meaning that they no longer mask greenhouse gas warming as much.[79]

In addition to their direct effects (scattering and absorbing solar radiation), aerosols have indirect effects on the Earth's radiation budget. Sulfate aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei and thus lead to clouds that have more and smaller cloud droplets. These clouds reflect solar radiation more efficiently than clouds with fewer and larger droplets.[80] This effect also causes droplets to be more uniform in size, which reduces the growth of raindrops and makes clouds more reflective to incoming sunlight.[81] Indirect effects of aerosols are the largest uncertainty in radiative forcing.[82]

While aerosols typically limit global warming by reflecting sunlight, black carbon in soot that falls on snow or ice can contribute to global warming. Not only does this increase the absorption of sunlight, it also increases melting and sea-level rise.[83] Limiting new black carbon deposits in the Arctic could reduce global warming by 0.2 °C (0.36 °F) by 2050.[84]

Changes of the land surface

Humans change the Earth's surface mainly to create more agricultural land. Today, agriculture takes up 34% of Earth's land area, while 26% is forests, and 30% is uninhabitable (glaciers, deserts, etc.).[86] The amount of forested land continues to decrease, largely due to conversion to cropland in the tropics.[87] This deforestation is the most significant aspect of land surface change affecting global warming. The main causes of deforestation are: permanent land-use change from forest to agricultural land producing products such as beef and palm oil (27%), logging to produce forestry/forest products (26%), short term shifting cultivation (24%), and wildfires (23%).[88]

In addition to affecting greenhouse gas concentrations, land-use changes affect global warming through a variety of other chemical and physical mechanisms. Changing the type of vegetation in a region affects the local temperature, by changing how much of the sunlight gets reflected back into space (albedo), and how much heat is lost by evaporation. For instance, the change from a dark forest to grassland makes the surface lighter, causing it to reflect more sunlight. Deforestation can also contribute to changing temperatures by affecting the release of aerosols and other chemical compounds that influence clouds, and by changing wind patterns.[89] In tropic and temperate areas the net effect is to produce significant warming, while at latitudes closer to the poles a gain of albedo (as forest is replaced by snow cover) leads to an overall cooling effect.[89] Globally, these effects are estimated to have led to a slight cooling, dominated by an increase in surface albedo.[90]

Solar and volcanic activity

Physical climate models are unable to reproduce the rapid warming observed in recent decades when taking into account only variations in solar output and volcanic activity.[91] As the Sun is the Earth's primary energy source, changes in incoming sunlight directly affect the climate system.[92] Solar irradiance has been measured directly by satellites,[93] and indirect measurements are available from the early 1600s.[92] There has been no upward trend in the amount of the Sun's energy reaching the Earth.[94] Further evidence for greenhouse gases being the cause of recent climate change come from measurements showing the warming of the lower atmosphere (the troposphere), coupled with the cooling of the upper atmosphere (the stratosphere).[95] If solar variations were responsible for the observed warming, warming of both the troposphere and the stratosphere would be expected, but that has not been the case.[56]

Explosive volcanic eruptions represent the largest natural forcing over the industrial era. When the eruption is sufficiently strong (with sulfur dioxide reaching the stratosphere) sunlight can be partially blocked for a couple of years, with a temperature signal lasting about twice as long. In the industrial era, volcanic activity has had negligible impacts on global temperature trends.[96] Present-day volcanic CO2 emissions are equivalent to less than 1% of current anthropogenic CO2 emissions.[97]

Climate change feedback

The response of the climate system to an initial forcing is modified by feedbacks: increased by self-reinforcing feedbacks and reduced by balancing feedbacks.[99] The main reinforcing feedbacks are the water-vapour feedback, the ice–albedo feedback, and probably the net effect of clouds.[100] The primary balancing feedback to global temperature change is radiative cooling to space as infrared radiation in response to rising surface temperature.[101] In addition to temperature feedbacks, there are feedbacks in the carbon cycle, such as the fertilizing effect of CO

2 on plant growth.[102] Uncertainty over feedbacks is the major reason why different climate models project different magnitudes of warming for a given amount of emissions.[103]

As air gets warmer, it can hold more moisture. After initial warming due to emissions of greenhouse gases, the atmosphere will hold more water. As water vapour is a potent greenhouse gas, this further heats the atmosphere.[100] If cloud cover increases, more sunlight will be reflected back into space, cooling the planet. If clouds become more high and thin, they act as an insulator, reflecting heat from below back downwards and warming the planet.[104] Overall, the net cloud feedback over the industrial era has probably exacerbated temperature rise.[105] The reduction of snow cover and sea ice in the Arctic reduces the albedo of the Earth's surface.[106] More of the Sun's energy is now absorbed in these regions, contributing to amplification of Arctic temperature changes.[107] Arctic amplification is also melting permafrost, which releases methane and CO

2 into the atmosphere.[108]

Around half of human-caused CO

2 emissions have been absorbed by land plants and by the oceans.[109] On land, elevated CO

2 and an extended growing season have stimulated plant growth. Climate change increases droughts and heat waves that inhibit plant growth, which makes it uncertain whether this carbon sink will continue to grow in the future.[110] Soils contain large quantities of carbon and may release some when they heat up.[111] As more CO

2 and heat are absorbed by the ocean, it acidifies, its circulation changes and phytoplankton takes up less carbon, decreasing the rate at which the ocean absorbs atmospheric carbon.[112] Climate change can increase methane emissions from wetlands, marine and freshwater systems, and permafrost.[113]

Future warming and the carbon budget

Future warming depends on the strengths of climate feedbacks and on emissions of greenhouse gases.[114] The former are often estimated using various climate models, developed by multiple scientific institutions.[115] A climate model is a representation of the physical, chemical, and biological processes that affect the climate system.[116] Models include changes in the Earth's orbit, historical changes in the Sun's activity, and volcanic forcing.[117] Computer models attempt to reproduce and predict the circulation of the oceans, the annual cycle of the seasons, and the flows of carbon between the land surface and the atmosphere.[118] Models project different future temperature rises for given emissions of greenhouse gases; they also do not fully agree on the strength of different feedbacks on climate sensitivity and magnitude of inertia of the climate system.[119]

The physical realism of models is tested by examining their ability to simulate contemporary or past climates.[120] Past models have underestimated the rate of Arctic shrinkage[121] and underestimated the rate of precipitation increase.[122] Sea level rise since 1990 was underestimated in older models, but more recent models agree well with observations.[123] The 2017 United States-published National Climate Assessment notes that "climate models may still be underestimating or missing relevant feedback processes".[124]

Various Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) can be used as input for climate models: "a stringent mitigation scenario (RCP2.6), two intermediate scenarios (RCP4.5 and RCP6.0) and one scenario with very high [greenhouse gas] emissions (RCP8.5)".[125] RCPs only look at concentrations of greenhouse gases, and so do not include the response of the carbon cycle.[126] Climate model projections summarized in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report indicate that, during the 21st century, the global surface temperature is likely to rise a further 0.3 to 1.7 °C (0.5 to 3.1 °F) in a moderate scenario, or as much as 2.6 to 4.8 °C (4.7 to 8.6 °F) in an extreme scenario, depending on the rate of future greenhouse gas emissions and on climate feedback effects.[127]

2 and other gases' CO

2-equivalents

A subset of climate models add societal factors to a simple physical climate model. These models simulate how population, economic growth, and energy use affect – and interact with – the physical climate. With this information, these models can produce scenarios of how greenhouse gas emissions may vary in the future. This output is then used as input for physical climate models to generate climate change projections.[128] In some scenarios emissions continue to rise over the century, while others have reduced emissions.[129] Fossil fuel resources are too abundant for shortages to be relied on to limit carbon emissions in the 21st century.[130] Emissions scenarios can be combined with modelling of the carbon cycle to predict how atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases might change in the future.[131] According to these combined models, by 2100 the atmospheric concentration of CO2 could be as low as 380 or as high as 1400 ppm, depending on the socioeconomic scenario and the mitigation scenario.[132]

The remaining carbon emissions budget is determined by modelling the carbon cycle and the climate sensitivity to greenhouse gases.[133] According to the IPCC, global warming can be kept below 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) with a two-thirds chance if emissions after 2018 do not exceed 420 or 570 gigatonnes of CO

2, depending on exactly how the global temperature is defined. This amount corresponds to 10 to 13 years of current emissions. There are high uncertainties about the budget; for instance, it may be 100 gigatonnes of CO

2 smaller due to methane release from permafrost and wetlands.[134]

Impacts

Physical environment

The environmental effects of climate change are broad and far-reaching, affecting oceans, ice, and weather. Changes may occur gradually or rapidly. Evidence for these effects comes from studying climate change in the past, from modelling, and from modern observations.[136] Since the 1950s, droughts and heat waves have appeared simultaneously with increasing frequency.[137] Extremely wet or dry events within the monsoon period have increased in India and East Asia.[138] The maximum rainfall and wind speed from hurricanes and typhoons is likely increasing.[8]

Global sea level is rising as a consequence of glacial melt, melt of the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, and thermal expansion. Between 1993 and 2017, the rise increased over time, averaging 3.1 ± 0.3 mm per year.[139] Over the 21st century, the IPCC projects that in a very high emissions scenario the sea level could rise by 61–110 cm.[140] Increased ocean warmth is undermining and threatening to unplug Antarctic glacier outlets, risking a large melt of the ice sheet[141] and the possibility of a 2-meter sea level rise by 2100 under high emissions.[142]

Climate change has led to decades of shrinking and thinning of the Arctic sea ice, making it vulnerable to atmospheric anomalies.[143] While ice-free summers are expected to be rare at 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) degrees of warming, they are set to occur once every three to ten years at a warming level of 2.0 °C (3.6 °F).[144] Higher atmospheric CO

2 concentrations have led to changes in ocean chemistry. An increase in dissolved CO

2 is causing oceans to acidify.[145] In addition, oxygen levels are decreasing as oxygen is less soluble in warmer water,[146] with hypoxic dead zones expanding as a result of algal blooms stimulated by higher temperatures, higher CO

2 levels, ocean deoxygenation, and eutrophication.[147]

Tipping points and long-term impacts

The greater the amount of global warming, the greater the risk of passing through ‘tipping points’, thresholds beyond which certain impacts can no longer be avoided even if temperatures are reduced.[148] An example is the collapse of West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, where a temperature rise of 1.5 to 2.0 °C (2.7 to 3.6 °F) may commit the ice sheets to melt, although the time scale of melt is uncertain and depends on future warming.[149][14] Some large-scale changes could occur over a short time period, such as a collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation,[150] which would trigger major climate changes in the North Atlantic, Europe, and North America.[151]

The long-term effects of climate change include further ice melt, ocean warming, sea level rise, and ocean acidification. On the timescale of centuries to millennia, the magnitude of climate change will be determined primarily by anthropogenic CO

2 emissions.[152] This is due to CO

2's long atmospheric lifetime.[152] Oceanic CO

2 uptake is slow enough that ocean acidification will continue for hundreds to thousands of years.[153] These emissions are estimated to have prolonged the current interglacial period by at least 100,000 years.[154] Sea level rise will continue over many centuries, with an estimated rise of 2.3 metres per degree Celsius (4.2 ft/°F) after 2000 years.[155]

Nature and wildlife

Recent warming has driven many terrestrial and freshwater species poleward and towards higher altitudes.[156] Higher atmospheric CO

2 levels and an extended growing season have resulted in global greening, whereas heatwaves and drought have reduced ecosystem productivity in some regions. The future balance of these opposing effects is unclear.[157] Climate change has contributed to the expansion of drier climate zones, such as the expansion of deserts in the subtropics.[158] The size and speed of global warming is making abrupt changes in ecosystems more likely.[159] Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the extinction of many species.[160]

The oceans have heated more slowly than the land, but plants and animals in the ocean have migrated towards the colder poles faster than species on land.[161] Just as on land, heat waves in the ocean occur more frequently due to climate change, with harmful effects found on a wide range of organisms such as corals, kelp, and seabirds.[162] Ocean acidification is impacting organisms who produce shells and skeletons, such as mussels and barnacles, and coral reefs; coral reefs have seen extensive bleaching after heat waves.[163] Harmful algae bloom enhanced by climate change and eutrophication cause anoxia, disruption of food webs and massive large-scale mortality of marine life.[164] Coastal ecosystems are under particular stress, with almost half of wetlands having disappeared as a consequence of climate change and other human impacts.[165]

|

Humans

The effects of climate change on humans, mostly due to warming and shifts in precipitation, have been detected worldwide. Regional impacts of climate change are now observable on all continents and across ocean regions,[170] with low-latitude, less developed areas facing the greatest risk.[171] Continued emission of greenhouse gases will lead to further warming and long-lasting changes in the climate system, with potentially “severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts” for both people and ecosystems.[172] Climate change risks are unevenly distributed, but are generally greater for disadvantaged people in developing and developed countries.[173]

Food and health

Health impacts include both the direct effects of extreme weather, leading to injury and loss of life,[174] as well as indirect effects, such as undernutrition brought on by crop failures.[175] Various infectious diseases are more easily transmitted in a warmer climate, such as dengue fever, which affects children most severely, and malaria.[176] Young children are the most vulnerable to food shortages, and together with older people, to extreme heat.[177] The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from heat exposure in elderly people, increases in diarrheal disease, malaria, dengue, coastal flooding, and childhood undernutrition.[178] Over 500,000 additional adult deaths are projected yearly by 2050 due to reductions in food availability and quality.[179] Other major health risks associated with climate change include air and water quality.[180] The WHO has classified human impacts from climate change as the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century.[181]

Climate change is affecting food security and has caused reduction in global mean yields of maize, wheat, and soybeans between 1981 and 2010.[182] Future warming could further reduce global yields of major crops.[183] Crop production will probably be negatively affected in low-latitude countries, while effects at northern latitudes may be positive or negative.[184] Up to an additional 183 million people worldwide, particularly those with lower incomes, are at risk of hunger as a consequence of these impacts.[185] The effects of warming on the oceans impact fish stocks, with a global decline in the maximum catch potential. Only polar stocks are showing an increased potential.[186] Regions dependent on glacier water, regions that are already dry, and small islands are at increased risk of water stress due to climate change.[187]

Livelihoods

Economic damages due to climate change have been underestimated, and may be severe, with the probability of disastrous tail-risk events being nontrivial.[188] Climate change has likely already increased global economic inequality, and is projected to continue doing so.[189] Most of the severe impacts are expected in sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia, where existing poverty is already exacerbated.[190] The World Bank estimates that climate change could drive over 120 million people into poverty by 2030.[191] Current inequalities between men and women, between rich and poor, and between different ethnicities have been observed to worsen as a consequence of climate variability and climate change.[192] An expert elicitation concluded that the role of climate change in armed conflict has been small compared to factors such as socio-economic inequality and state capabilities, but that future warming will bring increasing risks.[193]

Low-lying islands and coastal communities are threatened through hazards posed by sea level rise, such as flooding and permanent submergence.[194] This could lead to statelessness for populations in island nations, such as the Maldives and Tuvalu.[195] In some regions, rise in temperature and humidity may be too severe for humans to adapt to.[196] With worst-case climate change, models project that almost one-third of humanity might live in extremely hot and uninhabitable climates, similar to the current climate found mainly in the Sahara.[197] These factors, plus weather extremes, can drive environmental migration, both within and between countries.[198] Displacement of people is expected to increase as a consequence of more frequent extreme weather, sea level rise, and conflict arising from increased competition over natural resources. Climate change may also increase vulnerabilities, leading to "trapped populations" in some areas who are not able to move due to a lack of resources.[199]

|

Responses: mitigation and adaptation

Mitigation

Climate change impacts can be mitigated by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and by enhancing sinks that absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.[205] In order to limit global warming to less than 1.5 °C with a high likelihood of success, global greenhouse gas emissions needs to be net-zero by 2050, or by 2070 with a 2 °C target.[206] This requires far-reaching, systemic changes on an unprecedented scale in energy, land, cities, transport, buildings, and industry.[207] Scenarios that limit global warming to 1.5 °C often describe reaching net negative emissions at some point.[208] To make progress towards a goal of limiting warming to 2 °C, the United Nations Environment Programme estimates that, within the next decade, countries need to triple the amount of reductions they have committed to in their current Paris Agreements; an even greater level of reduction is required to meet the 1.5 °C goal.[209]

Although there is no single pathway to limit global warming to 1.5 or 2.0 °C (2.7 or 3.6 °F),[210] most scenarios and strategies see a major increase in the use of renewable energy in combination with increased energy efficiency measures to generate the needed greenhouse gas reductions.[211] To reduce pressures on ecosystems and enhance their carbon sequestration capabilities, changes would also be necessary in sectors such as forestry and agriculture.[212]

Other approaches to mitigating climate change entail a higher level of risk. Scenarios that limit global warming to 1.5 °C typically project the large-scale use of carbon dioxide removal methods over the 21st century.[213] There are concerns, though, about over-reliance on these technologies, as well as possible environmental impacts.[214] Solar radiation management (SRM) methods have also been explored as a possible supplement to deep reductions in emissions. However, SRM would raise significant ethical and legal issues, and the risks are poorly understood.[215]

Clean energy

Long-term decarbonisation scenarios point to rapid and significant investment in renewable energy,[217] which includes solar and wind power, bioenergy, geothermal energy, and hydropower.[218] Fossil fuels accounted for 80% of the world's energy in 2018, while the remaining share was split between nuclear power and renewables;[219] that mix is projected to change significantly over the next 30 years.[211] Solar and wind have seen substantial growth and progress over the last few years; photovoltaic solar and onshore wind are the cheapest forms of adding new power generation capacity in most countries.[220] Renewables represented 75% of all new electricity generation installed in 2019, with solar and wind constituting nearly all of that amount.[221] Meanwhile, nuclear power costs are increasing amidst stagnant power share, so that nuclear power generation is now several times more expensive per megawatt-hour than wind and solar.[222]

To achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, renewable energy would become the dominant form of electricity generation, rising to 85% or more by 2050 in some scenarios. The use of electricity for other needs, such as heating, would rise to the point where electricity becomes the largest form of overall energy supply.[223] Investment in coal would be eliminated and coal use nearly phased out by 2050.[224]

There are obstacles to the continued rapid development of renewables. For solar and wind power, a key challenge is their intermittency and seasonal variability. Traditionally, hydro dams with reservoirs and conventional power plants have been used when variable energy production is low. Intermittency can further be countered by demand flexibility, and by expanding battery storage and long-distance transmission to smooth variability of renewable output across wider geographic areas.[217] Some environmental and land use concerns have been associated with large solar and wind projects,[225] while bioenergy is often not carbon neutral and may have negative consequences for food security.[226] Hydropower growth has been slowing and is set to decline further due to concerns about social and environmental impacts.[227]

Clean energy improves human health by minimizing climate change and has the near-term benefit of reducing air pollution deaths,[228] which were estimated at 7 million annually in 2016.[229] Meeting the Paris Agreement goals that limit warming to a 2 °C increase could save about a million of those lives per year by 2050, whereas limiting global warming to 1.5 °C could save millions and simultaneously increase energy security and reduce poverty.[230]

Energy efficiency

Reducing energy demand is another major feature of decarbonisation scenarios and plans.[231] In addition to directly reducing emissions, energy demand reduction measures provide more flexibility for low carbon energy development, aid in the management of the electricity grid, and minimize carbon-intensive infrastructure development.[232] Over the next few decades, major increases in energy efficiency investment will be required to achieve these reductions, comparable to the expected level of investment in renewable energy.[233] However, several COVID-19 related changes in energy use patterns, energy efficiency investments, and funding have made forecasts for this decade more difficult and uncertain.[234]

Efficiency strategies to reduce energy demand vary by sector. In transport, gains can be made by switching passengers and freight to more efficient travel modes, such as buses and trains, and increasing the use of electric vehicles.[235] Industrial strategies to reduce energy demand include increasing the energy efficiency of heating systems and motors, designing less energy-intensive products, and increasing product lifetimes.[236] In the building sector the focus is on better design of new buildings, and incorporating higher levels of energy efficiency in retrofitting techniques for existing structures.[237] Buildings would see additional electrification with the use of technologies like heat pumps, which have higher efficiency than fossil fuels.[238]

Agriculture, industry and transport

Agriculture and forestry face a triple challenge of limiting greenhouse gas emissions, preventing the further conversion of forests to agricultural land, and meeting increases in world food demand.[239] A suite of actions could reduce agriculture/forestry-based greenhouse gas emissions by 66% from 2010 levels by reducing growth in demand for food and other agricultural products, increasing land productivity, protecting and restoring forests, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production.[240]

In addition to the industrial demand reduction measures mentioned earlier, steel and cement production, which together are responsible for about 13% of industrial CO

2 emissions, present particular challenges. In these industries, carbon-intensive materials such as coke and lime play an integral role in the production process. Reducing CO

2 emissions here requires research driven efforts aimed at decarbonizing the chemistry of these processes.[241] In transport, scenarios envision sharp increases in the market share of electric vehicles, and low carbon fuel substitution for other transportation modes like shipping.[242]

Carbon sequestration

2 emissions have been absorbed by carbon sinks, including plant growth, soil uptake, and ocean uptake (2020 Global Carbon Budget).

Natural carbon sinks can be enhanced to sequester significantly larger amounts of CO

2 beyond naturally occurring levels.[243] Reforestation and tree planting on non-forest lands are among the most mature sequestration techniques, although they raise food security concerns. Soil carbon sequestration and coastal carbon sequestration are less understood options.[244] The feasibility of land-based negative emissions methods for mitigation are uncertain in models; the IPCC has described mitigation strategies based on them as risky.[245]

Where energy production or CO

2-intensive heavy industries continue to produce waste CO

2, the gas can be captured and stored instead of being released to the atmosphere. Although its current use is limited in scale and expensive,[246] carbon capture and storage (CCS) may be able to play a significant role in limiting CO

2 emissions by mid-century.[247] This technique, in combination with bio-energy production (BECCS) can result in net-negative emissions, where the amount of greenhouse gasses that are released into the atmosphere are less than the sequestered, or stored, amount in the bio-energy fuel being grown.[248] It remains highly uncertain whether carbon dioxide removal techniques, such as BECCS, will be able to play a large role in limiting warming to 1.5 °C, and policy decisions based on reliance on carbon dioxide removal increases the risk of global warming increasing beyond international goals.[249]

Adaptation

Adaptation is "the process of adjustment to current or expected changes in climate and its effects".[250] Without additional mitigation, adaptation cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.[251] More severe climate change requires more transformative adaptation, which can be prohibitively expensive.[250] The capacity and potential for humans to adapt, called adaptive capacity, is unevenly distributed across different regions and populations, and developing countries generally have less.[252] The first two decades of the 21st century saw an increase in adaptive capacity in most low- and middle-income countries with improved access to basic sanitation and electricity, but progress is slow. Many countries have implemented adaptation policies. However, there is a considerable gap between necessary and available finance.[253]

Adaptation to sea level rise consists of avoiding at-risk areas, learning to live with increased flooding, protection and, if needed, the more transformative option of managed retreat.[254] There are economic barriers for moderation of dangerous heat impact: avoiding strenuous work or employing private air conditioning is not possible for everybody.[255] In agriculture, adaptation options include a switch to more sustainable diets, diversification, erosion control and genetic improvements for increased tolerance to a changing climate.[256] Insurance allows for risk-sharing, but is often difficult to obtain for people on lower incomes.[257] Education, migration and early warning systems can reduce climate vulnerability.[258]

Ecosystems adapt to climate change, a process that can be supported by human intervention. Possible responses include increasing connectivity between ecosystems, allowing species to migrate to more favourable climate conditions and species relocation. Protection and restoration of natural and semi-natural areas helps build resilience, making it easier for ecosystems to adapt. Many of the actions that promote adaptation in ecosystems, also help humans adapt via ecosystem-based adaptation. For instance, restoration of natural fire regimes makes catastrophic fires less likely, and reduces human exposure. Giving rivers more space allows for more water storage in the natural system, reducing flood risk. Restored forest act as a carbon sink, but planting trees in unsuitable regions can exacerbate climate impacts.[259]

There are some synergies and trade-offs between adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation measures often offer short-term benefits, whereas mitigation has longer-term benefits.[260] Increased use of air conditioning allows people to better cope with heat, but increases energy demand. Compact urban development may lead to reduced emissions from transport and construction. Simultaneously, it may increase the urban heat island effect, leading to higher temperatures and increased exposure.[261] Increased food productivity has large benefits for both adaptation and mitigation.[262]

Policies and politics

| High | Medium | Low | Very Low |

Countries that are most vulnerable to climate change have typically been responsible for a small share of global emissions, which raises questions about justice and fairness.[263] Climate change is strongly linked to sustainable development. Limiting global warming makes it easier to achieve sustainable development goals, such as eradicating poverty and reducing inequalities. The connection between the two is recognized in the Sustainable Development Goal 13 which is to "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts".[264] The goals on food, clean water and ecosystem protections have synergies with climate mitigation.[265]

The geopolitics of climate change is complex and has often been framed as a free-rider problem, in which all countries benefit from mitigation done by other countries, but individual countries would lose from investing in a transition to a low-carbon economy themselves. This framing has been challenged. For instance, the benefits in terms of public health and local environmental improvements of coal phase-out exceed the costs in almost all regions.[266] Another argument against this framing is that net importers of fossil fuels win economically from transitioning, causing net exporters to face stranded assets: fossil fuels they cannot sell.[267]

Policy options

A wide range of policies, regulations and laws are being used to reduce greenhouse gases. Carbon pricing mechanisms include carbon taxes and emissions trading systems.[268] As of 2019, carbon pricing covers about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[269] Direct global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, and $5.2 trillion when indirect costs such as air pollution are priced in.[270] Ending these can cause a 28% reduction in global carbon emissions and a 46% reduction in air pollution deaths.[271] Subsidies could also be redirected to support the transition to clean energy.[272] More prescriptive methods that can reduce greenhouse gases include vehicle efficiency standards, renewable fuel standards, and air pollution regulations on heavy industry.[273] Renewable portfolio standards have been enacted in several countries requiring utilities to increase the percentage of electricity they generate from renewable sources.[274]

As the use of fossil fuels is reduced, there are Just Transition considerations involving the social and economic challenges that arise. An example is the employment of workers in the affected industries, along with the well-being of the broader communities involved.[275] Climate justice considerations, such as those facing indigenous populations in the Arctic,[276] are another important aspect of mitigation policies.[277]

International climate agreements

2 emissions in China and the rest of world have surpassed the output of the United States and Europe.[278]

2 at a far faster rate than other primary regions.[278]

Nearly all countries in the world are parties to the 1994 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[279] The objective of the UNFCCC is to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.[280] As stated in the convention, this requires that greenhouse gas concentrations are stabilized in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, and economic development can be sustained.[281] Global emissions have risen since signing of the UNFCCC, which does not actually restrict emissions but rather provides a framework for protocols that do.[72] Its yearly conferences are the stage of global negotiations.[282]

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol extended the UNFCCC and included legally binding commitments for most developed countries to limit their emissions,[283] During Kyoto Protocol negotiations, the G77 (representing developing countries) pushed for a mandate requiring developed countries to "[take] the lead" in reducing their emissions,[284] since developed countries contributed most to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and since per-capita emissions were still relatively low in developing countries and emissions of developing countries would grow to meet their development needs.[285]

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord has been widely portrayed as disappointing because of its low goals, and was rejected by poorer nations including the G77.[286] Associated parties aimed to limit the increase in global mean temperature to below 2.0 °C (3.6 °F).[287] The Accord set the goal of sending $100 billion per year to developing countries in assistance for mitigation and adaptation by 2020, and proposed the founding of the Green Climate Fund.[288] As of 2020[update], the fund has failed to reach its expected target, and risks a shrinkage in its funding.[289]

In 2015 all UN countries negotiated the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global warming well below 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) and contains an aspirational goal of keeping warming under 1.5 °C.[290] The agreement replaced the Kyoto Protocol. Unlike Kyoto, no binding emission targets were set in the Paris Agreement. Instead, the procedure of regularly setting ever more ambitious goals and reevaluating these goals every five years has been made binding.[291] The Paris Agreement reiterated that developing countries must be financially supported.[292] As of February 2021[update], 194 states and the European Union have signed the treaty and 188 states and the EU have ratified or acceded to the agreement.[293]

The 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to stop emitting ozone-depleting gases, may have been more effective at curbing greenhouse gas emissions than the Kyoto Protocol specifically designed to do so.[294] The 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol aims to reduce the emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, a group of powerful greenhouse gases which served as a replacement for banned ozone-depleting gases. This strengthened the makes the Montreal Protocol a stronger agreement against climate change.[295]

National responses

In 2019, the United Kingdom parliament became the first national government in the world to officially declare a climate emergency.[296] Other countries and jurisdictions followed suit.[297] In November 2019 the European Parliament declared a "climate and environmental emergency",[298] and the European Commission presented its European Green Deal with the goal of making the EU carbon-neutral by 2050.[299] Major countries in Asia have made similar pledges: South Korea and Japan have committed to become carbon neutral by 2050, and China by 2060.[300]

As of 2021, based on information from 48 NDCs which represent 40% of the parties to the Paris Agreement, estimated total greenhouse gas emissions will be 0.5% lower compared to 2010 levels, below the 45% or 25% reduction goals to limit global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C, respectively.[301]

Scientific consensus and society

Scientific consensus

There is an overwhelming scientific consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused mainly by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases, with 90–100% (depending on the exact question, timing and sampling methodology) of publishing climate scientists agreeing.[303] The consensus has grown to 100% among research scientists on anthropogenic global warming as of 2019.[304] No scientific body of national or international standing disagrees with this view.[305] Consensus has further developed that some form of action should be taken to protect people against the impacts of climate change, and national science academies have called on world leaders to cut global emissions.[306]

Scientific discussion takes place in journal articles that are peer-reviewed, which scientists subject to assessment every couple of years in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.[307] In 2013, the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report stated that "it is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century".[308] Their 2018 report expressed the scientific consensus as: "human influence on climate has been the dominant cause of observed warming since the mid-20th century".[309] Scientists have issued two warnings to humanity, in 2017 and 2019, expressing concern about the current trajectory of potentially catastrophic climate change, and about untold human suffering as a consequence.[310]

The public

Climate change came to international public attention in the late 1980s.[311] Due to confusing media coverage in the early 1990s, understanding was often confounded by conflation with other environmental issues like ozone depletion.[312] In popular culture, the first movie to reach a mass public on the topic was The Day After Tomorrow in 2004, followed a few years later by the Al Gore documentary An Inconvenient Truth. Books, stories and films about climate change fall under the genre of climate fiction.[311]

Significant regional differences exist in both public concern for and public understanding of climate change. In 2015, a median of 54% of respondents considered it "a very serious problem", but Americans and Chinese (whose economies are responsible for the greatest annual CO2 emissions) were among the least concerned.[313] A 2018 survey found increased concern globally on the issue compared to 2013 in most countries. More highly educated people, and in some countries, women and younger people were more likely to see climate change as a serious threat. In the United States, there was a large partisan gap in opinion.[314]

Denial and misinformation

Public debate about climate change has been strongly affected by climate change denial and misinformation, which originated in the United States and has since spread to other countries, particularly Canada and Australia. The actors behind climate change denial form a well-funded and relatively coordinated coalition of fossil fuel companies, industry groups, conservative think tanks, and contrarian scientists.[316] Like the tobacco industry before, the main strategy of these groups has been to manufacture doubt about scientific data and results.[317] Many who deny, dismiss, or hold unwarranted doubt about the scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change are labelled as "climate change skeptics", which several scientists have noted is a misnomer.[318]

There are different variants of climate denial: some deny that warming takes place at all, some acknowledge warming but attribute it to natural influences, and some minimize the negative impacts of climate change.[319] Manufacturing uncertainty about the science later developed into a manufacturing controversy: creating the belief that there is significant uncertainty about climate change within the scientific community in order to delay policy changes.[320] Strategies to promote these ideas include criticism of scientific institutions,[321] and questioning the motives of individual scientists.[319] An echo chamber of climate-denying blogs and media has further fomented misunderstanding of climate change.[322]

Protest and litigation

Climate protests have risen in popularity in the 2010s in such forms as public demonstrations,[323] fossil fuel divestment, and lawsuits.[324] Prominent recent demonstrations include the school strike for climate, and civil disobedience. In the school strike, youth across the globe have protested by skipping school, inspired by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg.[325] Mass civil disobedience actions by groups like Extinction Rebellion have protested by causing disruption.[326] Litigation is increasingly used as a tool to strengthen climate action, with many lawsuits targeting governments to demand that they take ambitious action or enforce existing laws regarding climate change.[327] Lawsuits against fossil-fuel companies, from activists, shareholders and investors, generally seek compensation for loss and damage.[328]

Discovery

To explain why Earth's temperature was higher than expected considering only incoming solar radiation, Joseph Fourier proposed the existence of a greenhouse effect. Solar energy reaches the surface as the atmosphere is transparent to solar radiation. The warmed surface emits infrared radiation, but the atmosphere is relatively opaque to infrared and slows the emission of energy, warming the planet.[329] Starting in 1859,[330] John Tyndall established that nitrogen and oxygen (99% of dry air) are transparent to infrared, but water vapour and traces of some gases (significantly methane and carbon dioxide) both absorb infrared and, when warmed, emit infrared radiation. Changing concentrations of these gases could have caused "all the mutations of climate which the researches of geologists reveal" including ice ages.[331]

Svante Arrhenius noted that water vapour in air continuously varied, but carbon dioxide (CO

2) was determined by long term geological processes. At the end of an ice age, warming from increased CO

2 would increase the amount of water vapour, amplifying its effect in a feedback process. In 1896, he published the first climate model of its kind, showing that halving of CO

2 could have produced the drop in temperature initiating the ice age. Arrhenius calculated the temperature increase expected from doubling CO

2 to be around 5–6 °C (9.0–10.8 °F).[332] Other scientists were initially sceptical and believed the greenhouse effect to be saturated so that adding more CO

2 would make no difference. They thought climate would be self-regulating.[333] From 1938 Guy Stewart Callendar published evidence that climate was warming and CO

2 levels increasing,[334] but his calculations met the same objections.[333]

In the 1950s, Gilbert Plass created a detailed computer model that included different atmospheric layers and the infrared spectrum and found that increasing CO

2 levels would cause warming. In the same decade Hans Suess found evidence CO

2 levels had been rising, Roger Revelle showed the oceans would not absorb the increase, and together they helped Charles Keeling to begin a record of continued increase, the Keeling Curve.[333] Scientists alerted the public,[335] and the dangers were highlighted at James Hansen's 1988 Congressional testimony.[22] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, set up in 1988 to provide formal advice to the world's governments, spurred interdisciplinary research.[336]

See also

- 2020s in environmental history

- Anthropocene – proposed new geological time interval in which humans are having significant geological impact

- Global cooling – minority view held by scientists in the 1970s that imminent cooling of the Earth would take place

References

Notes

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 3 2017 Figure 3.1 panel 2, Figure 3.3 panel 5.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2013, p. 4: Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and the concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased; IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 54: Abundant empirical evidence of the unprecedented rate and global scale of impact of human influence on the Earth System (Steffen et al., 2016; Waters et al., 2016) has led many scientists to call for an acknowledgment that the Earth has entered a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.

- ^ EPA 2020: Carbon dioxide (76%), Methane (16%), Nitrous Oxide (6%).

- ^ EPA 2020: Carbon dioxide enters the atmosphere through burning fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, and oil), solid waste, trees and other biological materials, and also as a result of certain chemical reactions (e.g., manufacture of cement). Fossil fuel use is the primary source of CO

2. CO

2 can also be emitted from direct human-induced impacts on forestry and other land use, such as through deforestation, land clearing for agriculture, and degradation of soils. Methane is emitted during the production and transport of coal, natural gas, and oil. Methane emissions also result from livestock and other agricultural practices and by the decay of organic waste in municipal solid waste landfills. - ^ "Scientific Consensus: Earth's Climate is Warming". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. NASA JPL. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.; Gleick, 7 January 2017.

- ^ IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 7: Since the pre-industrial period, the land surface air temperature has risen nearly twice as much as the global average temperature (high confidence). Climate change... contributed to desertification and land degradation in many regions (high confidence).; IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 45: Climate change is playing an increasing role in determining wildfire regimes alongside human activity (medium confidence), with future climate variability expected to enhance the risk and severity of wildfires in many biomes such as tropical rainforests (high confidence).

- ^ IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 16: Over the last decades, global warming has led to widespread shrinking of the cryosphere, with mass loss from ice sheets and glaciers (very high confidence), reductions in snow cover (high confidence) and Arctic sea ice extent and thickness (very high confidence), and increased permafrost temperature (very high confidence).

- ^ a b USGCRP Chapter 9 2017, p. 260.

- ^ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR 2014, pp. 13–16; WHO, Nov 2015: "Climate change is the greatest threat to global health in the 21st century. Health professionals have a duty of care to current and future generations. You are on the front line in protecting people from climate impacts - from more heat-waves and other extreme weather events; from outbreaks of infectious diseases such as malaria, dengue and cholera; from the effects of malnutrition; as well as treating people that are affected by cancer, respiratory, cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases caused by environmental pollution."

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 64: Sustained net zero anthropogenic emissions of CO

2 and declining net anthropogenic non-CO

2 radiative forcing over a multi-decade period would halt anthropogenic global warming over that period, although it would not halt sea level rise or many other aspects of climate system adjustment. - ^ Trenberth & Fasullo 2016

- ^ a b "The State of the Global Climate 2020". World Meteorological Organization. 14 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ a b IPCC SR15 Summary for Policymakers 2018, p. 7

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR 2014, p. 77, 3.2

- ^ a b c NASA, Mitigation and Adaptation 2020

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR 2014, p. 17, SPM 3.2

- ^ Climate Action Tracker 2019, p. 1: Under current pledges, the world will warm by 2.8°C by the end of the century, close to twice the limit they agreed in Paris. Governments are even further from the Paris temperature limit in terms of their real-world action, which would see the temperature rise by 3°C.; United Nations Environment Programme 2019, p. 27.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch2 2018, pp. 95–96: In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5°C, global net anthropogenic CO

2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range); IPCC SR15 2018, p. 17, SPM C.3:All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence).; Rogelj et al. 2015; Hilaire et al. 2019 - ^ U.S. Geological Survey Circular. The Survey. 1933. p. 8.

- ^ NASA, 5 December 2008.

- ^ a b Weart "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988", "News reporters gave only a little attention ...".

- ^ Joo et al. 2015.

- ^ NOAA, 17 June 2015: "when scientists or public leaders talk about global warming these days, they almost always mean human-caused warming"; IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014, p. 120: "Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use."

- ^ NASA, 7 July 2020; Shaftel 2016: " 'Climate change' and 'global warming' are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. ... Global warming refers to the upward temperature trend across the entire Earth since the early 20th century ... Climate change refers to a broad range of global phenomena ...[which] include the increased temperature trends described by global warming."; Associated Press, 22 September 2015: "The terms global warming and climate change can be used interchangeably. Climate change is more accurate scientifically to describe the various effects of greenhouse gases on the world because it includes extreme weather, storms and changes in rainfall patterns, ocean acidification and sea level.".

- ^ Hodder & Martin 2009; BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020.

- ^ The Guardian, 17 May 2019; BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020.

- ^ USA Today, 21 November 2019.

- ^ Neukom et al. 2019.

- ^ a b "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change". NASA. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ EPA 2016: The U.S. Global Change Research Program, the National Academy of Sciences, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have each independently concluded that warming of the climate system in recent decades is "unequivocal". This conclusion is not drawn from any one source of data but is based on multiple lines of evidence, including three worldwide temperature datasets showing nearly identical warming trends as well as numerous other independent indicators of global warming (e.g. rising sea levels, shrinking Arctic sea ice).

- ^ IPCC SR15 Summary for Policymakers 2018, p. 4; WMO 2019, p. 6.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 81.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch2 2013, p. 162.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 57: This report adopts the 51-year reference period, 1850–1900 inclusive, assessed as an approximation of pre-industrial levels in AR5 ... Temperatures rose by 0.0 °C–0.2 °C from 1720–1800 to 1850–1900; Hawkins et al. 2017, p. 1844.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2013, pp. 4–5: "Global-scale observations from the instrumental era began in the mid-19th century for temperature and other variables ... the period 1880 to 2012 ... multiple independently produced datasets exist."

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch5 2013, p. 386; Neukom et al. 2019.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch5 2013, pp. 389, 399–400: "The PETM [around 55.5–55.3 million years ago] was marked by ... global warming of 4 °C to 7 °C ... Deglacial global warming occurred in two main steps from 17.5 to 14.5 ka [thousand years ago] and 13.0 to 10.0 ka."

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 54.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 2010, p. S26. Figure 2.5.

- ^ Kennedy et al. 2010, pp. S26, S59–S60; USGCRP Chapter 1 2017, p. 35.

- ^ IPCC AR4 WG2 Ch1 2007, Sec. 1.3.5.1, p. 99.

- ^ "Global Warming". NASA JPL. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

Satellite measurements show warming in the troposphere but cooling in the stratosphere. This vertical pattern is consistent with global warming due to increasing greenhouse gases but inconsistent with warming from natural causes.

- ^ IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Sutton, Dong & Gregory 2007.

- ^ "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". NOAA. 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch3 2013, p. 257: "Ocean warming dominates the global energy change inventory. Warming of the ocean accounts for about 93% of the increase in the Earth's energy inventory between 1971 and 2010 (high confidence), with warming of the upper (0 to 700 m) ocean accounting for about 64% of the total.

- ^ NOAA, 10 July 2011.

- ^ United States Environmental Protection Agency 2016, p. 5: "Black carbon that is deposited on snow and ice darkens those surfaces and decreases their reflectivity (albedo). This is known as the snow/ice albedo effect. This effect results in the increased absorption of radiation that accelerates melting."

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch12 2013, p. 1062; IPCC SROCC Ch3 2019, p. 212.

- ^ NASA, 12 September 2018.

- ^ Delworth & Zeng 2012, p. 5; Franzke et al. 2020.

- ^ National Research Council 2012, p. 9.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch10 2013, p. 916.

- ^ Knutson 2017, p. 443; IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch10 2013, pp. 875–876.

- ^ a b USGCRP 2009, p. 20.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2013, pp. 13–14.

- ^ NASA. "The Causes of Climate Change". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ IPCC AR4 WG1 Ch1 2007, FAQ1.1: "To emit 240 W m−2, a surface would have to have a temperature of around −19 °C (−2 °F). This is much colder than the conditions that actually exist at the Earth's surface (the global mean surface temperature is about 14 °C).

- ^ ACS. "What Is the Greenhouse Effect?". Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- ^ Ozone acts as a greenhouse gas in the lowest layer of the atmosphere, the troposphere (as opposed to the stratospheric ozone layer).Wang, Shugart & Lerdau 2017

- ^ Schmidt et al. 2010; USGCRP Climate Science Supplement 2014, p. 742.

- ^ The Guardian, 19 February 2020.

- ^ WMO 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Siegenthaler et al. 2005; Lüthi et al. 2008.

- ^ BBC, 10 May 2013.

- ^ Olivier & Peters 2019, pp. 14, 16–17, 23.

- ^ Our World in Data, 18 September 2020.

- ^ Olivier & Peters 2019, p. 17; Our World in Data, 18 September 2020; EPA 2020: Greenhouse gas emissions from industry primarily come from burning fossil fuels for energy, as well as greenhouse gas emissions from certain chemical reactions necessary to produce goods from raw materials; "Redox, extraction of iron and transition metals".

Hot air (oxygen) reacts with the coke (carbon) to produce carbon dioxide and heat energy to heat up the furnace. Removing impurities: The calcium carbonate in the limestone thermally decomposes to form calcium oxide. calcium carbonate → calcium oxide + carbon dioxide

; Kvande 2014: Carbon dioxide gas is formed at the anode, as the carbon anode is consumed upon reaction of carbon with the oxygen ions from the alumina (Al2O3). Formation of carbon dioxide is unavoidable as long as carbon anodes are used, and it is of great concern because CO2 is a greenhouse gas - ^ EPA 2020; Global Methane Initiative 2020: Estimated Global Anthropogenic Methane Emissions by Source, 2020: Enteric fermentation (27%), Manure Management (3%), Coal Mining (9%), Municipal Solid Waste (11%), Oil & Gas (24%), Wastewater (7%), Rice Cultivation (7%).

- ^ Michigan State University 2014: Nitrous oxide is produced by microbes in almost all soils. In agriculture, N2O is emitted mainly from fertilized soils and animal wastes – wherever nitrogen (N) is readily available.; EPA 2019: Agricultural activities, such as fertilizer use, are the primary source of N2O emissions; Davidson 2009: 2.0% of manure nitrogen and 2.5% of fertilizer nitrogen was converted to nitrous oxide between 1860 and 2005; these percentage contributions explain the entire pattern of increasing nitrous oxide concentrations over this period.

- ^ a b EPA 2019.

- ^ IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 10.

- ^ IPCC SROCC Ch5 2019, p. 450.

- ^ Haywood 2016, p. 456; McNeill 2017; Samset et al. 2018.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch2 2013, p. 183.

- ^ He et al. 2018; Storelvmo et al. 2016.

- ^ Ramanathan & Carmichael 2008.

- ^ Wild et al. 2005; Storelvmo et al. 2016; Samset et al. 2018.

- ^ Twomey 1977.

- ^ Albrecht 1989.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, p. 78.

- ^ Ramanathan & Carmichael 2008; RIVM 2016.

- ^ Sand et al. 2015.

- ^ World Resources Institute, 31 March 2021

- ^ Ritchie & Roser 2018

- ^ The Sustainability Consortium, 13 September 2018; UN FAO 2016, p. 18.

- ^ Curtis et al. 2018.

- ^ a b World Resources Institute, 8 December 2019.

- ^ IPCC SRCCL Ch2 2019, p. 172: "The global biophysical cooling alone has been estimated by a larger range of climate models and is −0.10 ± 0.14°C; it ranges from −0.57°C to +0.06°C ... This cooling is essentially dominated by increases in surface albedo: historical land cover changes have generally led to a dominant brightening of land".

- ^ Schmidt, Shindell & Tsigaridis 2014; Fyfe et al. 2016.

- ^ a b USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, p. 78.

- ^ National Research Council 2008, p. 6.

- ^ "Is the Sun causing global warming?". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ IPCC AR4 WG1 Ch9 2007, pp. 702–703; Randel et al. 2009.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, p. 79

- ^ Fischer & Aiuppa 2020.

- ^ "Thermodynamics: Albedo". NSIDC. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "The study of Earth as an integrated system". Vitals Signs of the Planet. Earth Science Communications Team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory / California Institute of Technology. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019..

- ^ a b USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, pp. 89–91.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, pp. 89–90.

- ^ CITEREFIPCC_AR5_WG12013

- ^ Wolff et al. 2015: "the nature and magnitude of these feedbacks are the principal cause of uncertainty in the response of Earth's climate (over multi-decadal and longer periods) to a particular emissions scenario or greenhouse gas concentration pathway."

- ^ Williams, Ceppi & Katavouta 2020.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, p. 90.

- ^ NASA, 28 May 2013.

- ^ Cohen et al. 2014.

- ^ a b Turetsky et al. 2019.

- ^ NASA, 16 June 2011: "So far, land plants and the ocean have taken up about 55 percent of the extra carbon people have put into the atmosphere while about 45 percent has stayed in the atmosphere. Eventually, the land and oceans will take up most of the extra carbon dioxide, but as much as 20 percent may remain in the atmosphere for many thousands of years."

- ^ IPCC SRCCL Ch2 2019, pp. 133, 144.

- ^ Melillo et al. 2017: Our first-order estimate of a warming-induced loss of 190 Pg of soil carbon over the 21st century is equivalent to the past two decades of carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 2 2017, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Dean et al. 2018.

- ^ Wolff et al. 2015

- ^ Carbon Brief, 15 January 2018, "Who does climate modelling around the world?".

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014, p. 120.

- ^ Carbon Brief, 15 January 2018, "What are the different types of climate models?".

- ^ Carbon Brief, 15 January 2018, "What is a climate model?".

- ^ Stott & Kettleborough 2002.

- ^ IPCC AR4 WG1 Ch8 2007, FAQ 8.1.

- ^ Stroeve et al. 2007; National Geographic, 13 August 2019.

- ^ Liepert & Previdi 2009.

- ^ Rahmstorf et al. 2007; Mitchum et al. 2018.

- ^ USGCRP Chapter 15 2017.

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR Summary for Policymakers 2014, Sec. 2.1.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Technical Summary 2013, pp. 79–80.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Technical Summary 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Carbon Brief, 15 January 2018, "What are the inputs and outputs for a climate model?".

- ^ Riahi et al. 2017; Carbon Brief, 19 April 2018.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG3 Ch5 2014, pp. 379–380.

- ^ Matthews et al. 2009.

- ^ Carbon Brief, 19 April 2018; Meinshausen 2019, p. 462.

- ^ Rogelj et al. 2019.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Summary for Policymakers 2018, p. 12.

- ^ NOAA 2017.

- ^ Hansen et al. 2016; Smithsonian, 26 June 2016.