Вступление

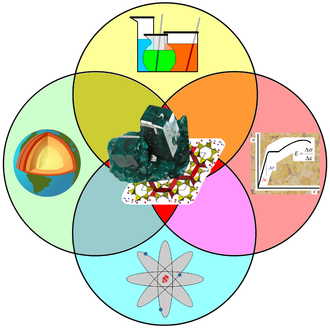

В геологии и минералогии , в минеральном или минеральных видах является, вообще говоря, твердым химическим соединение с достаточно хорошо определенным химической композицией и конкретные кристаллической структурой , которая встречается в природе в чистом виде.

Геологическое определение минерала обычно исключает соединения, которые встречаются только в живых существах. Однако некоторые минералы часто являются биогенными (например, кальцит ) или являются органическими соединениями в химическом смысле (например, меллит ). Более того, живые существа часто синтезируют неорганические минералы (например, гидроксилапатит ), которые также встречаются в горных породах. ( Полная статья ... )

Избранные общие статьи

Минералогия - это предмет геологии, специализирующейся на научном изучении химии , кристаллической структуры и физических (в том числе оптических ) свойств минералов и минерализованных артефактов . Конкретные исследования в области минералогии включают процессы происхождения и образования минералов, классификацию минералов, их географическое распределение, а также их использование. ( Полная статья ... )

Talc is a clay mineral, composed of hydrated magnesium silicate with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thickening agent and lubricant; is an ingredient in ceramics, paint, and roofing material; and is a main ingredient in many cosmetics. It occurs as foliated to fibrous masses, and in an exceptionally rare crystal form. It has a perfect basal cleavage and an uneven flat fracture, and it is foliated with a two-dimensional platy form.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 1 as the hardness of talc, the softest mineral. When scraped on a streak plate, talc produces a white streak; though this indicator is of little importance, because most silicate minerals produce a white streak. Talc is translucent to opaque, with colors ranging from whitish grey to green with a vitreous and pearly luster. Talc is not soluble in water, and is slightly soluble in dilute mineral acids. (Full article...)- A rich seam of iridescent opal encased in matrix

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·nH2O); its water content may range from 3 to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6 and 10%. Because of its amorphous character, it is classed as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms of silica, which are classed as minerals. It is deposited at a relatively low temperature and may occur in the fissures of almost any kind of rock, being most commonly found with limonite, sandstone, rhyolite, marl, and basalt.

There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. Precious opal displays play-of-color (iridescence), common opal does not. Play-of-color is defined as "a pseudo chromatic optical effect resulting in flashes of colored light from certain minerals, as they are turned in white light." The internal structure of precious opal causes it to diffract light, resulting in play-of-color. Depending on the conditions in which it formed, opal may be transparent, translucent, or opaque and the background color may be white, black, or nearly any color of the visual spectrum. Black opal is considered to be the rarest, whereas white, gray, and green are the most common. (Full article...)

Borax, also known as sodium borate, sodium tetraborate, or disodium tetraborate, is a compound with formula Na

2H

4B

4O

9•nH

2O or, more precisely, [Na•(H

2O)+

m]

2 [B

4O

5(OH)2−

4].

The formula is often improperly written as Na

2B

4O

7•(n+2)H

2O, reflecting an older incorrect understanding of the anion's molecular structure. The name may refer to any of a number of closely related boron-containing mineral or chemical compounds that differ in their water of crystallization content. The most commonly encountered one is the octahydrate Na

2H

4B

4O

9•8H

2O or [Na(H

2O)+

4]

2 [B

4O

5(OH)2−

4] (or Na

2B

4O

7•10H

2O, the "decahydrate", in the older notation). It is a colorless crystalline solid that dissolves in water. (Full article...)

Corundum is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide (Al

2O

3) typically containing traces of iron, titanium, vanadium and chromium. It is a rock-forming mineral. It is also a naturally transparent material, but can have different colors depending on the presence of transition metal impurities in its crystalline structure. Corundum has two primary gem varieties: ruby and sapphire. Rubies are red due to the presence of chromium, and sapphires exhibit a range of colors depending on what transition metal is present. A rare type of sapphire, padparadscha sapphire, is pink-orange.

The name "corundum" is derived from the Tamil-Dravidian word kurundam (ruby-sapphire) (appearing in Sanskrit as kuruvinda). (Full article...)- Dolomite (white) on talc

Dolomite ( /ˈdɒləmaɪt/) is an anhydrous carbonate mineral composed of calcium magnesium carbonate, ideally CaMg(CO3)2. The term is also used for a sedimentary carbonate rock composed mostly of the mineral dolomite. An alternative name sometimes used for the dolomitic rock type is dolostone. (Full article...) - The 423-carat (85 g) blue Logan Sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide (α-Al2O3) with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. It is typically blue, but natural "fancy" sapphires also occur in yellow, purple, orange, and green colors; "parti sapphires" show two or more colors. Red corundum stones also occur but are called rubies not sapphires. Pink colored corundum may be classified either as ruby or sapphire depending on locale.

Commonly, natural sapphires are cut and polished into gemstones and worn in jewelry. They also may be created synthetically in laboratories for industrial or decorative purposes in large crystal boules. Because of the remarkable hardness of sapphires – 9 on the Mohs scale (the third hardest mineral, after diamond at 10 and moissanite at 9.5) – sapphires are also used in some non-ornamental applications, such as infrared optical components, high-durability windows, wristwatch crystals and movement bearings, and very thin electronic wafers, which are used as the insulating substrates of special-purpose solid-state electronics such as integrated circuits and GaN-based blue LEDs.

Sapphire is the birthstone for September and the gem of the 45th anniversary. A sapphire jubilee occurs after 65 years. (Full article...) - Galena with minor pyrite

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It crystallizes in the cubic crystal system often showing octahedral forms. It is often associated with the minerals sphalerite, calcite and fluorite. (Full article...) - Brazilian trigonal hematite crystal

Hematite, also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of Fe

2O

3. It has the same crystal structure as corundum (Al

2O

3) and ilmenite (FeTiO

3). With this it forms a complete solid solution at temperatures above 950 °C (1,740 °F).

Hematite naturally occurs in black to steel or silver-gray, brown to reddish-brown, or red colors. It is mined as an important ore of iron. It is electrically conductive. Hematite varieties include kidney ore, martite (pseudomorphs after magnetite), iron rose and specularite (specular hematite). While these forms vary, they all have a rust-red streak. Hematite is not only harder than pure iron, but also much more brittle. Maghemite is a polymorph of hematite (γ-Fe

2O

3) with the same chemical formula, but with a spinel structure like magnetite. (Full article...)

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, blackboard/sidewalk chalk, and drywall. A massive fine-grained white or lightly tinted variety of gypsum, called alabaster, has been used for sculpture by many cultures including Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Rome, the Byzantine Empire, and the Nottingham alabasters of Medieval England. Gypsum also crystallizes as translucent crystals of selenite. It forms as an evaporite mineral and as a hydration product of anhydrite.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness defines hardness value 2 as gypsum based on scratch hardness comparison. (Full article...)- A sample of andesite (dark groundmass) with amygdaloidal vesicles filled with zeolite. Diameter of view is 8 cm.

Andesite ( /ˈændɪsaɪt/ or /ˈændɪzaɪt/) is an extrusive volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between basalt and rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

Andesite is the extrusive equivalent of plutonic diorite. Characteristic of subduction zones, andesite represents the dominant rock type in island arcs. The average composition of the continental crust is andesitic. Along with basalts they are a major component of the Martian crust. (Full article...)

Cinnabar (/ˈsɪnəbɑːr/) or cinnabarite (/sɪnəˈbɑːraɪt/), likely deriving from the Ancient Greek: κιννάβαρι (kinnabari), is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining elemental mercury, and is the historic source for the brilliant red or scarlet pigment termed vermilion and associated red mercury pigments.

Cinnabar generally occurs as a vein-filling mineral associated with recent volcanic activity and alkaline hot springs. The mineral resembles quartz in symmetry and in its exhibiting birefringence. Cinnabar has a mean refractive index near 3.2, a hardness between 2.0 and 2.5, and a specific gravity of approximately 8.1. The color and properties derive from a structure that is a hexagonal crystalline lattice belonging to the trigonal crystal system, crystals that sometimes exhibit twinning. (Full article...)- Three varieties of beryl (left to right): morganite, aquamarine and emerald

Beryl (/ˈbɛrəl/ BERR-əl) is a mineral composed of beryllium aluminium cyclosilicate with the chemical formula Be3Al2Si6O18. Well-known varieties of beryl include emerald and aquamarine. Naturally occurring, hexagonal crystals of beryl can be up to several meters in size, but terminated crystals are relatively rare. Pure beryl is colorless, but it is frequently tinted by impurities; possible colors are green, blue, yellow, and red (the rarest). Beryl can also be black in color. It is an ore source of beryllium. (Full article...) - Fibrous tremolite asbestos on muscovite

Asbestos (pronounced: /æsˈbɛstəs/ or /æsˈbɛstɒs/) is a naturally-occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere by abrasion and other processes. Asbestos is an excellent electrical insulator and is highly heat-resistant, so for many years it was used as a building material. However, it is now a well-known health and safety hazard and the use of asbestos as a building material is illegal in many countries. Inhalation of asbestos fibres can lead to various serious lung conditions, including asbestosis and cancer.

Archaeological studies have found evidence of asbestos being used as far back as the Stone Age to strengthen ceramic pots, but large-scale mining began at the end of the 19th century when manufacturers and builders began using asbestos for its desirable physical properties. (Full article...) - Amethyst cluster from Magaliesburg, South Africa.

Amethyst is a violet variety of quartz. The name comes from the Koine Greek αμέθυστος amethystos from α- a-, "not" and μεθύσκω (Ancient Greek) methysko / μεθώ metho (Modern Greek), "intoxicate", a reference to the belief that the stone protected its owner from drunkenness. The ancient Greeks wore amethyst and carved drinking vessels from it in the belief that it would prevent intoxication.

Amethyst is a semiprecious stone that is often used in jewelry and is the traditional birthstone for February. (Full article...) - Crystal structure of sodium chloride (table salt)

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns that repeat along the principal directions of three-dimensional space in matter.

The smallest group of particles in the material that constitutes this repeating pattern is the unit cell of the structure. The unit cell completely reflects the symmetry and structure of the entire crystal, which is built up by repetitive translation of the unit cell along its principal axes. The translation vectors define the nodes of the Bravais lattice. (Full article...) - Quartz crystal cluster from Tibet

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silicon and oxygen atoms. The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical formula of SiO2. Quartz is the second most abundant mineral in Earth's continental crust, behind feldspar.

Quartz exists in two forms, the normal α-quartz and the high-temperature β-quartz, both of which are chiral. The transformation from α-quartz to β-quartz takes place abruptly at 573 °C (846 K; 1,063 °F). Since the transformation is accompanied by a significant change in volume, it can easily induce fracturing of ceramics or rocks passing through this temperature threshold. (Full article...) - A lustrous crystal of zircon perched on a tan matrix of calcite from the Gilgit District of Pakistan

Zircon ( /ˈzɜːrkɒn/ or /ˈzɜːrkən/) is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates, and it is a source of the metal zirconium. Its chemical name is zirconium silicate, and its corresponding chemical formula is ZrSiO4. A common empirical formula showing some of the range of substitution in zircon is (Zr1–y, REEy)(SiO4)1–x(OH)4x–y. Zircon forms in silicate melts with large proportions of high field strength incompatible elements. For example, hafnium is almost always present in quantities ranging from 1 to 4%. The crystal structure of zircon is tetragonal crystal system. The natural colour of zircon varies between colourless, yellow-golden, red, brown, blue and green.

The name derives from the Persian zargun, meaning "gold-hued". This word is corrupted into "jargoon", a term applied to light-colored zircons. The English word "zircon" is derived from Zirkon, which is the German adaptation of this word. Yellow, orange and red zircon is also known as "hyacinth", from the flower hyacinthus, whose name is of Ancient Greek origin. (Full article...) - A rock containing three crystals of pyrite (FeS2). The crystal structure of pyrite is primitive cubic, and this is reflected in the cubic symmetry of its natural crystal facets.

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of these crystals:- Primitive cubic (abbreviated cP and alternatively called simple cubic)

- Body-centered cubic (abbreviated cI or bcc)

- Face-centered cubic (abbreviated cF or fcc, and alternatively called cubic close-packed or ccp)

Each is subdivided into other variants listed below. Note that although the unit cell in these crystals is conventionally taken to be a cube, the primitive unit cell often is not. (Full article...) - Deep green isolated fluorite crystal resembling a truncated octahedron, set upon a micaceous matrix, from Erongo Mountain, Erongo Region, Namibia (overall size: 50 mm × 27 mm, crystal size: 19 mm wide, 30 g)

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 4 as Fluorite. (Full article...) - Green fluorite with prominent cleavage

Cleavage, in mineralogy, is the tendency of crystalline materials to split along definite crystallographic structural planes. These planes of relative weakness are a result of the regular locations of atoms and ions in the crystal, which create smooth repeating surfaces that are visible both in the microscope and to the naked eye. If bonds in certain directions are weaker than others, the crystal will tend to split along the weakly bonded planes. These flat breaks are termed "cleavage." The classic example of cleavage is mica, which cleaves in a single direction along the basal pinacoid, making the layers seem like pages in a book. In fact mineralogists often refer to "books of mica."

Diamond and graphite provide examples of cleavage. Both are composed solely of a single element, carbon. But in diamond, each carbon atom is bonded to four others in a tetrahedral pattern with short covalent bonds. The planes of weakness (cleavage planes) in a diamond are in four directions, following the faces of the octahedron. (Full article...)

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually referring to hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ions, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common endmembers is written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH,F,Cl)2, and the crystal unit cell formulae of the individual minerals are written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, Ca10(PO4)6F2 and Ca10(PO4)6Cl2.

The mineral was named apatite by the German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner in 1786, although the specific mineral he had described was reclassified as fluorapatite in 1860 by the German mineralogist Karl Friedrich August Rammelsberg. Apatite is often mistaken for other minerals. This tendency is reflected in the mineral's name, which is derived from the Greek word απατείν (apatein), which means to deceive or to be misleading. (Full article...)- The diamond crystal structure belongs to the face-centered cubic lattice, with a repeated two-atom pattern.

In crystallography, the terms crystal system, crystal family, and lattice system each refer to one of several classes of space groups, lattices, point groups, or crystals. Informally, two crystals are in the same crystal system if they have similar symmetries, although there are many exceptions to this.

Crystal systems, crystal families, and lattice systems are similar but slightly different, and there is widespread confusion between them: in particular the trigonal crystal system is often confused with the rhombohedral lattice system, and the term "crystal system" is sometimes used to mean "lattice system" or "crystal family". (Full article...) - Main ruby producing countries

A ruby is a pink to blood-red coloured gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum (aluminium oxide). Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires. Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, together with amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the element chromium.

Some gemstones that are popularly or historically called rubies, such as the Black Prince's Ruby in the British Imperial State Crown, are actually spinels. These were once known as "Balas rubies". (Full article...)

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrated phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone and ornamental stone for thousands of years owing to its unique hue. Like most other opaque gems, turquoise has been devalued by the introduction onto the market of treatments, imitations and synthetics.

The gemstone has been known by many names. Pliny the Elder referred to the mineral as callais (from Ancient Greek κάλαϊς) and the Aztecs knew it as chalchihuitl. The word turquoise dates to the 17th century and is derived from the French turquois meaning "Turkish" because the mineral was first brought to Europe through Turkey from mines in the historical Khorasan of Iran (Persia). (Full article...)

Избранный минералог

Карл Фридрих Август Раммельсберг (1 апреля 1813 - 28 декабря 1899) был немецким минералогом из Берлина, Пруссия . ( Полная статья ... )

Carl Linnaeus (/lɪˈniːəs, lɪˈneɪəs/; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement as Carl von Linné (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈkɑːɭ fɔn lɪˈneː] (listen)), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the "father of modern taxonomy". Many of his writings were in Latin, and his name is rendered in Latin as Carolus Linnæus (after 1761 Carolus a Linné).

Linnaeus was born in Råshult, the countryside of Småland, in southern Sweden. He received most of his higher education at Uppsala University and began giving lectures in botany there in 1730. He lived abroad between 1735 and 1738, where he studied and also published the first edition of his Systema Naturae in the Netherlands. He then returned to Sweden where he became professor of medicine and botany at Uppsala. In the 1740s, he was sent on several journeys through Sweden to find and classify plants and animals. In the 1750s and 1760s, he continued to collect and classify animals, plants, and minerals, while publishing several volumes. He was one of the most acclaimed scientists in Europe at the time of his death. (Full article...)- Achille Delesse

Achille Ernest Oscar Joseph Delesse (3 February 1817 – 24 March 1881) was a French geologist and mineralogist.

He was born at Metz. At the age of twenty he entered the École Polytechnique, and subsequently passed through the Ecole des Mines. In 1845, he was appointed to the chair of mineralogy and geology at Besançon; in 1850, to the chair of geology at the Sorbonne in Paris; and in 1864, professor of agriculture at the Ecole des Mines. In 1878, he became inspector-general of mines. (Full article...) - Lehmann in the age of 42

Johann Gottlob Lehmann (4 August 1719 – 22 January 1767) was a German mineralogist and geologist noted for his work and research contributions to the geologic record leading to the development of stratigraphy. (Full article...) - Jens Esmark

Jens Esmark (31 January 1763 – 26 January 1839) was a Danish-Norwegian professor of mineralogy who contributed to many of the initial discoveries and conceptual analyses of glaciers, specifically the concept that glaciers had covered larger areas in the past. (Full article...) - Armand Dufrénoy

Ours-Pierre-Armand Petit-Dufrénoy (5 September 1792 – 20 March 1857) was a French geologist and mineralogist. (Full article...) - Johann Nepomuk von Fuchs

Johann Nepomuk von Fuchs (15 May 1774 – 5 March 1856) was a German chemist and mineralogist, and royal Bavarian privy councillor. (Full article...) - Augustin-Alexis Damour

Augustin Alexis Damour (19 July 1808, in Paris – 22 September 1902, in Paris) was a French mineralogist who was also interested in prehistory. (Full article...) Laminaria bongardiana

by Postels

Alexander Filippovich Postels (Russian: Александр Филиппович Постельс; 24 August 1801 Dorpat – 26 June 1871 Vyborg), was a Baltic German of Russian citizenship naturalist, mineralogist and artist.

Postels studied at St.Petersburg Imperial University and in 1826 lectured there on inorganic chemistry. (Full article...)

Giuseppe Gabriel Balsamo-Crivelli (1 September 1800, in Milan – 15 November 1874, in Pavia) was an Italian naturalist.

He became a professor of mineralogy and zoology at the University of Pavia in 1851, and was appointed professor of comparative anatomy in 1863. He was interested in various domains of natural history, and identified the fungus responsible for the white muscardine disease of silkworms, Beauveria bassiana. (Full article...)- François Michel de Rozière (29 September 1775, Melun – 4 November 1842, Melun) was a French mining engineer and mineralogist. (Full article...)

- Teachers of the Forestry Academy in Eberswalde (ca. 1868); Adolf Remelé, 3rd figure from the right (standing).

Adolf Karl Remelé (17 July 1839, Uerdingen – 16 November 1915, Eberswalde) was a German geologist and mineralogist.

He received his education at the University of Bonn, at the École des Mines in Paris and from the University of Berlin, receiving his doctorate in 1864 with the dissertation "De rubro uranico". In 1867 he qualified as a lecturer at Berlin, and during the following year, succeeded Lothar Meyer at the Forestry Academy in Eberswalde, where he taught classes in chemistry, geognosy and mineralogy. (Full article...) - Karpinsky in 1928

Alexander Petrovich Karpinsky (Russian: Александр Петрович Карпинский, trl. Aljeksandr Pjetrovič Karpinskij; 7 January 1847 (NS) – 15 July 1936) was a prominent Russian and Soviet geologist and mineralogist, and the president of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and later Academy of Sciences of the USSR, in 1917–1936. (Full article...) - Silliman around 1850

Benjamin Silliman (August 8, 1779 – November 24, 1864) was an early American chemist and science educator. He was one of the first American professors of science, at Yale College, the first person to distill petroleum in America, and a founder of the American Journal of Science, the oldest continuously published scientific journal in the United States. (Full article...) - Alfred Wilhelm Stelzner

Alfred Wilhelm Stelzner (20 December 1840, Dresden – 25 February 1895, Wiesbaden) was a German geologist.

From 1859 to 1864 he was a student at the Bergakademie Freiberg, an institute where he later served as inspector. From 1871 to 1874 he was a professor of mineralogy and geology at the University of Córdoba in Argentina. In 1874 he returned to the Bergakademie at Freiberg, where he succeeded his former teacher, Bernhard von Cotta. Here, he taught classes until his death in 1895. (Full article...) - Johann Gottlob von Kurr (15 January 1798, Sulzbach an der Murr – 9 May 1870, Stuttgart) was a German pharmacist and naturalist, making contributions in the fields of botany and mineralogy.

He worked for several years as a pharmacist in Calw and other communities, then later studied medicine and surgery at the University of Tübingen, where in 1832 he received doctorates for both disciplines. From 1832 to 1870 he taught classes in natural history at the vocational school in Stuttgart (in 1841 it became known as a polytechnic institute). He was a member of the Vereins für vaterländische Naturkunde in Württemberg (Association for Natural History in Württemberg) , and from 1844, was curator of its geognostic-paleontological collections. (Full article...) - Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton by Alexander Roslin

Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton (29 May 1716 – 1 January 1800) was a French naturalist and contributor to the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. (Full article...) - Ernst Friedrich Germar

Ernst Friedrich Germar (3 November 1786 – 8 July 1853) was a German professor and director of the Mineralogical Museum at Halle. As well as being a mineralogist he was interested in entomology and particularly in the Coleoptera and Hemiptera. He monographed the heteropteran family Scutelleridae.

In 1845, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. (Full article...)

Gustav Tschermak von Seysenegg (19 April 1836 – 24 May 1927) was an Austrian mineralogist. (Full article...)- Hanns Bruno Geinitz

Hanns Bruno Geinitz (16 October 1814 – 28 January 1900) was a German geologist, born at Altenburg, the capital of Saxe-Altenburg.

He was educated at the universities of Berlin and Jena, and gained the foundations of his geological knowledge under Friedrich August von Quenstedt. In 1837 he took the degree of Ph.D. with a thesis on the Muschelkalk of Thuringia. In 1850 he became professor of geology and mineralogy in the Royal Polytechnic School at Dresden, and in 1857 he was made director of the Royal Mineralogical and Geological Museum; he held these posts until 1894. (Full article...) - Sobolev, Vladimir Stepanovich (17 May 1908 in Lugansk – 1 September 1982 in Moscow) was a Russian geologist, working in mineralogy, petrology and theory of metamorphism. He was born in Lugansk, and died in Moscow. Sobolev predicted deposits of diamonds in Eastern Siberia. (Full article...)

- Johan Gottlieb Gahn

Johan Gottlieb Gahn (19 August 1745 – 8 December 1818) was a Swedish chemist and metallurgist who discovered manganese in 1774.

Gahn studied in Uppsala 1762 – 1770 and became acquainted with chemists Torbern Bergman and Carl Wilhelm Scheele. 1770 he settled in Falun, where he introduced improvements in copper smelting, and participated in building up several factories, including those for vitriol, sulfur and red paint. (Full article...) - Stanley Hay Umphray Bowie FRS (born 24 March 1917, in Bixter, Shetland - died 3 September 2008) was a Scottish geologist. He was considered a "world authority on uranium geology and a leader in the field of geochemistry and mineralogy". He developed methods and tools to identify opaque minerals using micro-indentation hardness and optical reflectance. He worked for the British Geological Survey between 1946 and 1977. The mineral bowieite was so named in recognition of his work on identification of opaque minerals. (Full article...)

- Johan Gottschalk Wallerius (11 July 1709 – 16 November 1785) was a Swedish chemist and mineralogist. (Full article...)Johan Gottschalk Wallerius

- John Flett in 1935

Sir John Smith Flett KBE FRSE FRS FGS (26 June 1869 – 26 January 1947) was a Scottish physician and geologist. (Full article...)

Увлекаться

Ресурсы для редакторов и сотрудничество с другими редакторами по улучшению статей Википедии, связанных с минералами, см. В WikiProject Rocks and Minerals .

Выбранные изображения

Эпидот часто имеет характерный фисташковый цвет.

Когда минералы вступают в реакцию, продукты иногда принимают форму реагента; продукт-минерал называется псевдоморфозом (или после) реагента. Здесь проиллюстрирован псевдоморф каолинита после ортоклаза . Здесь псевдоморф сохранил обычное для ортоклаза карловарское двойникование .

Алмаз - самый твердый природный материал, его твердость по шкале Мооса 10.

Гипсовая роза пустыни

Сфалерита кристалл частично заключен в кальцит из девонских свиты Милуоки в штате Висконсин

Черный андрадит, конечный член группы ортосиликатных гранатов.

Асбестиформный тремолит , часть группы амфиболов подкласса иносиликатов

Мусковит, минеральный вид в группе слюды, в подклассе филлосиликатов

Хюбнерит , богатый марганцем конечный член серии вольфрамита , с небольшим количеством кварца на заднем плане.

Идеальное базальное расщепление, наблюдаемое в биотите (черный), и хорошее расщепление, наблюдаемое в матриксе (розовый ортоклаз ).

Эгирин , железо-натриевый клинопироксен, является частью подкласса иносиликатов.

Галенит , PbS, является минералом с высоким удельным весом.

Пример эльбаита, разновидности турмалина, с характерными цветными полосами.

Сланец - метаморфическая порода, характеризующаяся обилием пластинчатых минералов. В этом примере в породе видны порфиробласты силлиманита размером до 3 см (1,2 дюйма).

Самородное золото. Редкий образец массивных кристаллов, растущих на центральной ножке, размером 3,7 x 1,1 x 0,4 см, из Венесуэлы.

Красная киноварь (HgS), ртутная руда, на доломите.

Контактные близнецы, как видно из шпинели

Карнотит (желтый) - это радиоактивный урансодержащий минерал.

Топаз имеет характерную ромбическую удлиненную кристаллическую форму.

Натролит - это минеральная группа из группы цеолитов; этот образец имеет очень заметную форму игольчатых кристаллов.

Розовые кубические кристаллы галита (NaCl; класс галогенидов) на матрице нахколита (NaHCO 3 ; карбонат и минеральная форма бикарбоната натрия, используемого в качестве пищевой соды ).

Кристаллы серандита , натролита , анальцима и эгирина из Мон-Сен-Илер, Квебек, Канада

Пирит имеет металлический блеск.

Подкатегории

- Выберите [►], чтобы просмотреть подкатегории

Вы знали ...?

- ... что редкий минерал матлокит ( PbFCl ) (на фото) назван в честь города в Дербишире ?

- ... что аморфный фосфат минерал азовскит был назван в честь итальянского горного округа Санта - Барбара , где он был обнаружен в 2003 году, но его имя также чтит святые Варвары , то покровитель из шахтеров ?

- ... что когда желтые кристаллы из mosesite , очень редкий минерал найден в месторождениях ртути , нагревают до 186 ° C (367 ° F), они становятся изотропными ?

Подтемы

Связанная Викимедиа

Очистить кеш сервера