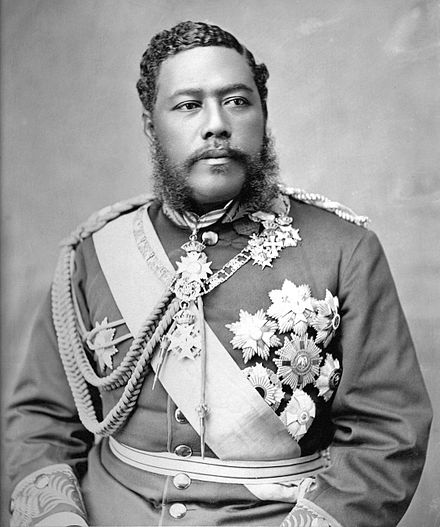

| Kalākaua | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Король Гавайских островов ( подробнее ... ) | ||||

| Царствовать | 12 февраля 1874 г. - 20 января 1891 г. | |||

| Инвеститура Коронация |

| |||

| Предшественник | Луналило | |||

| Преемник | Лилиуокалани | |||

| Родившийся | 16 ноября 1836 г., Гонолулу , Королевство Гавайи. | |||

| Умер | 20 января 1891 г. (54 года) Сан-Франциско, Калифорния , США | |||

| Захоронение | 15 февраля 1891 г. [1] | |||

| Супруг | Капиолани | |||

| ||||

| жилой дом | Дом Калакауа | |||

| Отец | Цезарь Капаакеа | |||

| Мама | Аналеа Кеохокалоле | |||

| Религия | Церковь Гавайев | |||

| Подпись | ||||

Калакауа (Дэвид Лааме Камананакапу Махинулани Налояэхуокалани Лумиалани Калакауа; [2] 16 ноября 1836 - 20 января 1891), иногда называемый Монархом Мерри , был последним королем и предпоследним монархом Королевства Гавайи , правившим с 12 февраля 1874 года. до его смерти. Преемник Луналило , он был избран на вакантный трон Гавайев против королевы Эммы . Калакауа был веселым человеком и любил развлекать гостей своим пением и игрой на укулеле . Во время его коронации и юбилея в честь его дня рождения хула , запрещенная для публики в королевстве, стала праздником гавайской культуры.

Во время его правления Договор о взаимности 1875 года принес королевству большое процветание. Его обновление продолжило процветание, но позволило Соединенным Штатам эксклюзивно использовать Перл-Харбор . В 1881 году он совершил кругосветное путешествие, чтобы стимулировать иммиграцию контрактных рабочих сахарных плантаций. Калакауа хотел, чтобы гавайцы расширили свое образование за пределы своей страны. Он учредил финансируемую государством программу по спонсированию квалифицированных студентов, которые будут отправлены за границу для дальнейшего обучения. Два проекта Калакауа, статуя Камехамеха I и восстановление дворца Иолани , были дорогостоящими затратами, но сегодня они являются популярными туристическими достопримечательностями.

Экстравагантные расходы и его планы создания полинезийской конфедерации сыграли на руку аннексионистам, которые уже работали над захватом Гавайев Соединенными Штатами. В 1887 году на него оказали давление, чтобы он подписал новую конституцию, которая сделала монархию не более чем номинальной позицией. Он верил в способности своей сестры Лилиуокалани править в качестве регента, когда назвал ее своим наследником после смерти их брата, Уильяма Питта Лелейохоку II , в 1877 году. После его смерти она стала последним монархом Гавайев.

Ранняя жизнь и семья [ править ]

Калакауа родился в 2 часа ночи 16 ноября 1836 года в семье Цезаря Калуайку Капаакеа и Анали Кеохокалоле в травяной хижине, принадлежащей его деду по материнской линии Айканака , у подножия кратера Панчбоул в Гонолулу на острове Оаху . [3] [4] Из али'и класса гавайской знати, его семья считалась родственной связью правящего Дома Камехамеха , разделяя общее происхождение от али'и нуи Кеаве'икекахиали'иокамоку 18-го века . От своих биологических родителей он произошел от Кеавеахулу иКамеейамоку , два из пяти королевских советников Камехамеха I во время его завоевания Королевства Гавайи . Камеейамоку, дедушка своей матери и отца, был одним из королевских близнецов рядом с Каманавой, изображенным на гавайском гербе. [5] Однако Калакауа и его братья и сестры проследили свой высокий ранг по линии происхождения своей матери, называя себя членами «линии Кэаве-а-Хеулу», хотя более поздние историки будут называть эту семью Домом Калакауа . [6] Второй выживший ребенок в большой семье, его биологические братья и сестры включали его старшего брата Джеймса Калиокалани и младших братьев и сестер.Лидия Камакаэха (позже переименованная в Лилиуокалани) , Анна Каиулани , Кайминауао , Мириам Ликелике и Уильям Питт Лелейохоку II . [7]

Учитывая имя Калакауа, что переводится как «День битвы», дата его рождения совпала с подписанием неравного договора, наложенного британским капитаном лордом Эдвардом Расселом из Актеона на Камехамеха III . Он и его братья и сестры были ханаи (неофициально усыновлены) для других членов семьи по коренным гавайским традициям. До рождения, его родители обещали дать ребенку в HanAi к Куини Лилиха , высокопоставленного chiefess и вдовы главного Верховного Бокий . Однако после его рождения верховная вождь Хаахео Канью отвезла ребенка в Хонуакаха, резиденцию короля. Кухина Нуи (регент)Элизабет Кинау , которая не любила Лилиху, решила и распорядилась передать его родителям Хаахео и ее мужу Кеавеамахи Кинимака. [3] [4] Когда Хаахео умер в 1843 году, она завещала ему все свое имущество. [8] После смерти Хаахео его опека была возложена на его отца ханаи , который был вождем меньшего ранга; он взял Калакауа, чтобы жить в Лахайне . Позже Кинимака вышла замуж за Пая, подчиненного таитянского вождя, которая относилась к Калакауа как к своей собственной до рождения собственного сына. [4] [9]

Образование [ править ]

В возрасте четырех лет Калакауа вернулся в Оаху, чтобы начать свое образование в Детской школе вождей (позже переименованной в Королевскую школу). Камехамеха III официально провозгласил его и его одноклассников правомочными на трон Королевства Гавайи. [10] Среди его одноклассников были его братья и сестры Джеймс Калиокалани и Лидия Камакаэха и их тринадцать королевских кузенов, включая будущих королей Камехамеха IV , Камехамеха V и Луналило . Их обучали американские миссионеры Амос Старр Кук и его жена Джульетта Монтегю Кук. [11] В школе Калакауа свободно говорил на английском и гавайском языках.и был известен своим весельем и юмором, а не академической доблестью. Сильный мальчик защищал своего менее крепкого старшего брата Калиокалани от старших мальчиков в школе. [3] [12]

В октябре 1840 года их дед по отцовской линии Каманава II попросил своих внуков навестить его в ночь перед казнью за убийство его жены Камокуики . На следующее утро Куки позволили опекуну королевских детей Иоанну Папа Ти привести Калиокалани и Калакауа, чтобы увидеть Каманаву в последний раз. Неизвестно, водили ли к нему и их сестру. [13] [14] Более поздние источники, особенно в биографиях Калакауа, указывали, что мальчики были свидетелями публичного повешения своего деда на виселице. [15] [16] Историк Хелена Г. Аллен отметила безразличие Куков к просьбе и травматическому опыту, который она, должно быть, вызвала у мальчиков.[15]

После того, как Куки вышли на пенсию и закрыли школу в 1850 году, он некоторое время учился в английской школе Джозефа Ватта для местных детей в Кавайахао, а затем присоединился к перемещенной дневной школе (также называемой Королевской школой), которой руководил преподобный Эдвард Беквит. Из-за болезни он не смог закончить школу, и его отправили обратно в Лахайну, чтобы он жил с матерью. [3] [12] После формального образования он изучал право у Чарльза Коффина Харриса в 1853 году. Калакауа назначил Харриса председателем Верховного суда Гавайев в 1877 году. [17] [18]

Политическая и военная карьера [ править ]

Различные должности Калакауа в армии, правительстве и суде не позволили ему полностью завершить юридическое образование. Первую военную подготовку он получил у прусского офицера майора Фрэнсиса Функ , который внушал восхищение прусской военной системой. [19] [12] В 1852 году принц Лихолихо, который позже правил как Камехамеха IV, назначил Калакауа одним из своих адъютантов в своем военном штабе. В следующем году он назначил Калакауа бреветским капитаном пехоты. [20] [21] В армии Калакауа служил старшим лейтенантом в ополчении своего отца Капаакеа из 240 человек, а затем работал военным секретарем у майора Джона Уильяма Эллиота Майкая., генерал-адъютант армии. [19] [12] Его повысили до майора и назначили в личный состав Камехамеха IV, когда король взошел на трон в 1855 году. Он был повышен до звания полковника в 1858 году. [20] [12]

Он стал личным соратником и другом принца Лота, будущего Камехамеха V, который привил молодому Калакауа свою миссию «Гавайи для гавайцев». [22] Осенью 1860 года, когда он был главным секретарем Департамента внутренних дел королевства, Калакауа сопровождал принца Лота, верховного вождя Леви Хаалелеа и гавайского консула в Перу Джозайю С. Сполдинга в двухмесячном туре по Великобритании. Колумбия и Калифорния. [23] Они отплыли из Гонолулу на борту яхты « Эмма Рук» 29 августа, прибыв 18 сентября в Викторию, Британская Колумбия, где их приняли местные высокопоставленные лица города. [23]В Калифорнии группа посетила Сан-Франциско , Сакраменто , Фолсом и другие местные районы, где их приняли с честью. [24]

В 1856 году Камехамеха IV назначил Калакауа членом Тайного государственного совета . Он также был назначен в Дом дворян, верхний орган Законодательного собрания Королевства Гавайи в 1858 году, где работал до 1873 года. [25] [26] Он служил третьим главным секретарем Департамента внутренних дел в 1859 году при князь Лот , который был министром внутренних дел , прежде чем стать королем в 1863. Он занимал эту должность до 1863. [12] [27] на 30 июня 1863, Kalakaua был назначен почт и служил до своей отставки 18 марта 1865. [ 12] [28]В 1865 году он был назначен королевским камергером и проработал до 1869 года, когда ушел в отставку, чтобы закончить юридическое образование. В 1870 году он был допущен к гавайской коллегии адвокатов и был нанят клерком в Земельном управлении, должность, которую он занимал, пока не взошел на трон. [12] [29] Он был награжден кавалером Королевского Ордена Камехамеха I в 1867 году. [20] [12]

Американский писатель Марк Твен , работавший разъездным репортером в Sacramento Daily Union , посетил Гавайи в 1866 году во время правления Камехамеха V. Он встретился с молодым Калакауа и другими членами законодательного собрания и отметил:

Достопочтенный Дэвид Калакауа, который в настоящее время занимает должность королевского камергера, - человек красивой внешности, образованный джентльмен и человек хороших способностей. Ему приближается к сорока, я полагаю, тридцать пять, во всяком случае. Он консервативен, политичен и расчетлив, мало выставляется напоказ и мало говорит в законодательном собрании. Он тихий, величавый, разумный человек, и он не станет дискредитировать королевскую власть. Король имеет право назначать своего преемника. Если он так поступит, его выбор, вероятно, падет на Калакауа. [30]

Брак [ править ]

Калакауа был ненадолго помолвлен с принцессой Викторией Камамалу , младшей сестрой Камехамеха IV и Камехамеха V. Однако брак был расторгнут, когда принцесса решила возобновить свое временное обручение со своим кузеном Луналило. Позже Калакауа влюбился в Капиолани , молодую вдову Беннета Намакеха , дядю жены Камехамеха IV королевы Эммы . Потомок короля Kaumuali'i из Кауаи , Kapi'olani была королевы Эммы дама в ожидании , и принц Альберт Эдвард Kamehameha медсестра и сторож «s. Они поженились 19 декабря 1863 года на тихой церемонии, проведенной англиканским министром.Церковь Гавайев . Время свадьбы подверглось резкой критике, поскольку она пришлась на официальный траур по королю Камехамехе IV. [31] [32] Брак остался бездетным. [33]

Политическое превосходство [ править ]

Выборы 1873 г. [ править ]

Король Камехамеха V умер 12 декабря 1872 года, не назвав наследника престола. Согласно Конституции Королевства Гавайи 1864 года , если король не назначал преемника, новый король был назначен законодательным собранием, чтобы начать новую королевскую линию преемственности. [34]

Было несколько кандидатов на гавайский трон, в том числе Бернис Пауахи Бишоп , которую Камехамеха V попросил унаследовать трон на смертном одре, но она отклонила это предложение. Тем не менее, борьба была сосредоточена на двух высокопоставленных мужчинах- али , или вождях: Луналило и Калакауа. Луналило был более популярен, отчасти потому, что он был более высокопоставленным вождем, чем Калакауа, и был ближайшим двоюродным братом Камехамеха В. Луналило был также более либеральным из двух - он пообещал внести поправки в конституцию, чтобы дать людям больший голос в парламенте. правительство. По словам историка Ральфа С. Кейкендалла, среди сторонников Луналило был энтузиазм по поводу провозглашения его королем без проведения выборов. В ответ Луналило издал прокламацию, в которой говорилось, что, хотя он считал себя законным наследником престола, он согласится на выборы на благо королевства. [35] 1 января 1873 г. были проведены всенародные выборы на пост короля Гавайев. Луналило победил с подавляющим большинством голосов, в то время как Калакауа выступил крайне плохо, получив 12 голосов из более чем 11 000 поданных. [36] На следующий день законодательный орган подтвердил голосование и единогласно избрал Луналило. Калакауа уступил. [37]

Выборы 1874 г. [ править ]

Following Lunalilo's ascension, Kalākaua was appointed as colonel on the military staff of the king.[38] He kept politically active during Lunalilo's reign, including leadership involvement with a political organization known as the Young Hawaiians; the group's motto was "Hawaii for the Hawaiians".[38] He had gained political capital with his staunch opposition to ceding any part of the Hawaiian islands to foreign interests.[39][40] During the ʻIolani Barracks mutiny by the Royal Guards of Hawaii in September 1873, Kalākaua was suspected to have incited the native guards to rebel against their white officers. Lunalilo responded to the insurrection by disbanding the military unit altogether, leaving Hawaii without a standing army for the remainder of his reign.[41]

The issue of succession was a major concern especially since Lunalilo was unmarried and childless at the time. Queen Dowager Emma, the widow of Kamehameha IV, was considered to be Lunalilo's favorite choice as his presumptive heir.[42] On the other hand, Kalākaua and his political cohorts actively campaigned for him to be named successor in the event of the king's death.[38] Among the other candidates considered viable as Lunalilo's successor was the previously mentioned Bernice Pauahi Bishop. She had strong ties to the United States through her marriage to wealthy American businessman Charles Reed Bishop who also served as one of Lunalilo's cabinet ministers. When Lunalilo became ill several months after his election, Native Hawaiians counseled with him to appoint a successor to avoid another election. However he may have personally felt about Emma, he never put it in writing. He failed to act on the issue of a successor, and died on February 3, 1874, setting in motion a bitter election.[43] While Lunalilo did not think of himself as a Kamehameha, his election continued the Kamehameha line to some degree[44] making him the last of the monarchs of the Kamehameha dynasty.[45]

Pauahi chose not to run. Kalākaua's political platform was that he would reign in strict accordance with the kingdom's constitution. Emma campaigned on her assurance that Lunalilo had personally told her he wanted her to succeed him. Several individuals who claimed first-hand knowledge of Lunalilo's wishes backed her publicly. With Lunalilo's privy council issuing a public denial of that claim, the kingdom was divided on the issue.[46] British Commissioner James Hay Wodehouse put the British and American forces docked at Honolulu on the alert for possible violence.[47]

The election was held on February 12, and Kalākaua was elected by the Legislative Assembly by a margin of thirty-nine to six. His election provoked the Honolulu Courthouse riot where supporters of Queen Emma targeted legislators who supported Kalākaua; thirteen legislators were injured. The kingdom was without an army since the mutiny the year before and many police officers sent to quell the riot joined the mob or did nothing. Unable to control the mob, Kalākaua and Lunalilo's former ministers had to request the aid of American and British military forces docked in the harbor to put down the uprising.[47][40]

Reign[edit]

Given the unfavorable political climate following the riot, Kalākaua was quickly sworn in the following day, in a ceremony witnessed by government officials, family members, foreign representatives and some spectators. This inauguration ceremony was held at Kīnaʻu Hale, the residence of the Royal Chamberlain, instead of Kawaiahaʻo Church, as was customary. The hastiness of the affair would prompt him to hold a coronation ceremony in 1883.[48] Upon ascending to the throne, Kalākaua named his brother, William Pitt Leleiohoku, Leleiohoku II, as his heir-apparent.[49] When Leleiohoku II died in 1877, Kalākaua changed the name of his sister Lydia Dominis to Liliuokalani and designated her as his heir-apparent.[50]

From March to May 1874, he toured the main Hawaiian Islands of Kauai, Maui, Hawaii Island, Molokai and Oahu and visited the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement.[51]

Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 and its extension[edit]

Within a year of Kalākaua's election, he helped negotiate the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875. This free trade agreement between the United States and Hawaii, allowed sugar and other products to be exported to the US duty-free. He led the Reciprocity Commission consisting of sugar planter Henry A. P. Carter of C. Brewer & Co., Hawaii Chief Justice Elisha Hunt Allen, and Minister of Foreign Affairs William Lowthian Green. Kalākaua became the first reigning monarch to visit America. The state dinner in his honor hosted by President Ulysses S. Grant was the first White House state dinner ever held.[52]

Many in the Hawaii business community were willing to cede Pearl Harbor to the United States in exchange for the treaty, but Kalākaua was opposed to the idea. A seven-year treaty was signed on January 30, 1875, without any Hawaiian land being ceded.[53] San Francisco sugar refiner Claus Spreckels became a major investor in Hawaii's sugar industry. Initially, he bought half of the first year's production; ultimately he became the plantations' major shareholder.[54] Spreckels became one of Kalākaua's close associates.[55]

When it expired, an extension of the treaty was negotiated, giving exclusive use of Pearl Harbor to the United States. Ratifications by both parties took two years and eleven months, and were exchanged on December 9, 1887, extending the agreement for an additional seven years.[56]

Over the term of Kalākaua's reign, the treaty had a major effect on the kingdom's income. In 1874, Hawaii exported $1,839,620.27 in products. The value of exported products in 1890, the last full year of his reign, was $13,282,729.48, an increase of 722%. The export of sugar during that period grew from 24,566,611 pounds to 330,822,879 pounds.[57]

Education of Hawaiian Youths Abroad[edit]

The Education of Hawaiian Youths Abroad was a government-funded educational program during Kalākaua's reign to help students further their education beyond the institutions available in Hawaii at that time. Between 1880 and 1887, Kalākaua selected 18 students for enrollment in a university or apprenticeship to a trade, outside the Kingdom of Hawaii. These students furthered their education in Italy, England, Scotland, China, Japan and California. During the life of the program, the legislature appropriated $100,000 to support it.[58] When the Bayonet Constitution went into effect, the students were recalled to Hawaii.[59]

Trip around the world[edit]

King Kalākaua and his boyhood friends William Nevins Armstrong and Charles Hastings Judd, along with personal cook Robert von Oelhoffen, circumnavigated the globe in 1881. The purpose of the 281-day trip was to encourage the importation of contract labor for plantations. Kalākaua set a world record as the first monarch to travel around the world.[60] He appointed his sister and heir-apparent Liliuokalani to act as Regent during his absence.[61]

Setting sail on January 20, they visited California before sailing to Asia. There they spent four months opening contract labor dialogue in Japan and China, while sightseeing and spreading goodwill through nations that were potential sources for workers.[62] They continued through Southeast Asia, and then headed for Europe in June, where they stayed until mid-September.[63] Their most productive immigration talks were in Portugal, where Armstrong stayed behind to negotiate an expansion of Hawaii's existing treaty with the government.[64]

President James A. Garfield in Washington, D.C. had been assassinated in their absence. On their return trip to the United States, Kalākaua paid a courtesy call on Garfield's successor President Chester A. Arthur.[65]Before embarking on a train ride across the United States, Kalākaua visited Thomas Edison for a demonstration of electric lighting, discussing its potential use in Honolulu.[66]

They departed for Hawaii from San Francisco on October 22, arriving in Honolulu on October 31. His homecoming celebration went on for days. He had brought the small island nation to the attention of world leaders, but the trip had sparked rumors that the kingdom was for sale. In Hawaii there were critics who believed the labor negotiations were just his excuse to see the world. Eventually, his efforts bore fruit in increased contract labor for Hawaii.[67]

Thomas Thrum's Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1883 reported Kalākaua's tour expense appropriated by the government as $22,500,[68] although his personal correspondence indicates he exceeded that early on.[69]

ʻIolani Palace[edit]

'Iolani Palace is the only royal palace on US soil.[70] The first palace was a coral and wood structure which served primarily as office space for the kingdom's monarchs beginning with Kamehameha III in 1845. By the time Kalākaua became king, the structure had decayed, and he ordered it destroyed to be replaced with a new building.[71] During the 1878 session of the legislature Finance Chairman Walter Murray Gibson, a political supporter of Kalākaua's, pushed through appropriations of $50,000 for the new palace.[72]

Construction began in 1879, with an additional $80,000 appropriated later to furnish it and complete the construction.[73] Three architects worked on the design, Thomas J. Baker, Charles J. Wall and Isaac Moore.[74] December 31, 1879, the 45th birthday of Queen Kapiʻolani, was the date Kalākaua chose for the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone. Minister of Foreign Affairs John Mākini Kapena delivered the ceremony's formal address in Hawaiian.[75] As Master of the Freemason Lodge Le Progres de L'Oceanie, Kalākaua charged the freemasons with orchestrating the ceremonies. The parade preceding the laying of the cornerstone involved every civilian and military organization in Hawaii. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser noted it was "one of the largest seen in Honolulu for some years".[76] A copper time capsule containing photographs, documents, currency, and the Hawaiian census was sealed inside the cornerstone. After speeches had been made, the freemasons presented the king with "the working tools of a mason", a plumb bob, level, square tool, and a trowel.[76]

In between the laying of the cornerstone and the finishing of the new palace, Kalākaua had seen how other monarchs lived. He wanted ʻIolani to measure up to the standards of the rest of the world. The furnishing and interiors of the finished palace were reflective of that. Immediately upon completion, the king invited all 120 members of Lodge Le Progres de L'Oceanie to the palace for a lodge meeting.[77] Kalākaua had also seen during his visit to Edison's studio how effective electric lighting could be for the kingdom. On July 21, 1886, ʻIolani Palace led the way with the first electric lights in the kingdom, showcasing the technology. The monarch invited the public to attend a lighting ceremony on the palace grounds, attracting 5,000 spectators. The Royal Hawaiian Band entertained, refreshments were served, and the king paraded his troops around the grounds.[78][79] The total cost of building and furnishing the new palace was $343,595.[71]

1883 coronation[edit]

Kalākaua and Kapiʻolani had been denied a coronation ceremony in 1874 because of the civil unrest following the election. Under Finance Chairman Gibson, the 1880 legislature appropriated $10,000 for a coronation.[80] Gibson was believed to be the main proponent behind the event. On October 10, 1882, the Saturday Press indicated that not all the public was in favor of the coronation. By this point, Gibson's role in the kingdom's finances and his influence on Kalākaua were beginning to come under scrutiny: "Our versatile Premier ... is pulling another string in this puppet farce." At the same time, the newspaper rebuked many of the recent actions and policies not only of Gibson but of the King's cabinet in general.[81]

The coronation ceremony and related celebratory events were spread out over a two-week period.[82] A special octagon-shaped pavilion and grandstand were built for the February 12, 1883, ceremony. Preparations were made for an anticipated crowd exceeding 5,000, with lawn chairs to accommodate any overflow. Before the actual event, a procession of 630 adults and children paraded from downtown to the palace. Kalākaua and Kapiʻolani, accompanied by their royal retinue, came out of the palace onto the event grounds. The coronation was preceded by a choir singing and the formal recitation of the King's official titles. The news coverage noted, "The King looked ill at ease." Chief Justice of Hawaii's Supreme Court Albert Francis Judd officiated and delivered the oath of office to the king. The crown was then handed to Kalākaua, and he placed it upon his head. The ceremony ended with the choir singing, and a prayer. A planned post-coronation reception by Kalākaua and Kapiʻolani was cancelled without advance notice.[2] Today, Kalākaua's coronation pavilion serves as the bandstand for the Royal Hawaiian Band.[71]

Following the ceremony, Kalākaua unveiled the Kamehameha Statue in front of Aliiolani Hale, the government building, with Gibson delivering the unveiling speech.[83] This statue was a second replica. Originally intended for the centennial of Captain James Cook's landing in Hawaii, the statue, which was the brainchild of Gibson, had been cast by Thomas Ridgeway Gould but had been lost during shipment off the Falkland Islands. By the time the replica arrived, the intended date had passed, and it was decided to unveil the statue as part of the coronation ceremony. Later, the original statue was salvaged and restored. It was sent to Kohala, Hawaii, Kamehameha's birthplace, where it was unveiled by the king on May 8. The legislature had allocated $10,000 for the first statue and insured it for $12,000. A further $7,000 was allocated for the second statue with an additional $4,000 from the insurance money spent to add four bas relief panels depicting historic moments during Kamehamena's reign.[84]

That evening, the royal couple hosted a state dinner, and there was a luau at a later day. The hula was performed nightly on the palace grounds. Regattas, horse races and a number of events filled the celebration period.[82] Due to weather conditions, the planned illumination of the palace and grounds for the day of the coronation happened a week later, and the public was invited to attend. Fireworks displays lit up the sky at the palace and at Punchbowl Crater. A grand ball was held the evening of February 20.[83]

Although exact figures are unknown, historian Kuykendall stated that the final cost of the coronation exceeded $50,000.[82]

Kalākaua coinage[edit]

The Kalākaua coinage was minted to boost Hawaiian pride. At this time, United States gold coins had been accepted for any debt over $50; any debt under $50 was payable by US silver coins.[85] In 1880, the legislature passed a currency law that allowed it to purchase bullion for the United States mint to produce Hawaii's own coins.[86] The design would have the King's image on the obverse side, with Hawaii's coat of arms and motto "Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono" on the reverse. In a deal with Claus Spreckels, he sponsored the minting by purchasing the required silver. In return, he was guaranteed an equal amount of six percent gold bonds, thereby giving him a guaranteed profit.[87]

When Hawaii's silver coins began circulating in December 1883, the business community was reluctant to accept them, fearing they would drive US gold coins out of the market. Spreckels opened his own bank to circulate them.[88] Business owners feared economic inflation and lost faith in the government, as did foreign governments. Political fallout from the coinage led to the 1884 election-year shift towards the Kuokoa (independent) Party in the legislature. It passed the Currency Act to restrict acceptance of silver coins as payment for debts under $10. Exchange of silver for gold at the treasury was then limited to $150,000 a month. In 1903, the Hawaii silver coins were redeemed for US silver and melted down at the San Francisco Mint.[89]

Birthday Jubilee, November 15–29, 1886[edit]

Kalākaua's 50th birthday on November 16, 1886, was celebrated with a two-week jubilee. Gibson had by this time joined the King's cabinet as prime minister of Hawaii. He and Minister of the Interior Luther Aholo put forth a motion for the legislature to form a committee to oversee the birthday jubilee on September 20. The motion was approved, and at Gibson's subsequent request, the legislature appropriated $15,000 for the jubilee.[90] An announcement was made on November 3 that all government schools would be closed the week of November 15.[91]

Gifts for the king began arriving on November 15. At midnight, the jubilee officially began with fireworks at the Punchbowl Crater. At sunrise, the kingdom's police force arrived at ʻIolani Palace to pay tribute, followed by the king's Cabinet, Supreme Court justices, the kingdom's diplomats, and officials of government departments. School student bodies and civic organizations also paid tribute. The Royal Hawaiian Band played throughout the day. In the afternoon, the doors of the palace were opened to all the officials and organizations, and the public. In the evening, the palace was aglow with lanterns, candles and electric lighting throwing "a flood of radiance over the Palace and grounds".[92] The evening ended with a Fireman's Parade and fireworks. Throughout the next two weeks, there was a regatta, a Jubilee ball, a luau, athletic competitions, a state dinner, and a marksmanship contest won by the Honolulu Rifles.[93] Harper's Weekly reported in 1891 that the final cost of the jubilee was $75,000.[94]

Military policy[edit]

During the early part of his reign, Kalākaua restored the Household Guards which had been defunct since his predecessor Lunalilo abolished the unit in 1874. Initially, the king created three volunteer companies: the Leleiohoku Guard, a cavalry unit; the Prince's Own, an artillery unit; and the Hawaiian Guards, an infantry unit.[41][95] By the latter part of his reign, the army of the Kingdom of Hawaii consisted of six volunteer companies including the King's Own, the Queen's Own, the Prince's Own, the Leleiohoku Guard, the Mamalahoa Guard and the Honolulu Rifles, and the regular troops of the King's Household Guard. The ranks of these regiments were composed mainly of Hawaiian and part-Hawaiian officers with a few white officers including his brother-in-law John Owen Dominis. Each unit was subject to call for active service when necessary. The king and the governor of Oahu also had their own personal staff of military officers with the ranks of colonel and major.[96]

On October 1, 1886, the Military Act of 1886 was passed which created a Department of War and a Department of the Navy under the Minister of Foreign Affairs who would also serve as Secretary of War and of the Navy. Dominis was appointed lieutenant general and commander-in-chief and other officers were commissioned while the king was made the supreme commander and generalissimo of the Hawaiian Army.[96][97] Around this time, the government also bought and commissioned His Hawaiian Majesty's Ship (HHMS) Kaimiloa, the first and only vessel of the Hawaiian Royal Navy, under the command of Captain George E. Gresley Jackson.[98][99]

After 1887, the military commissions creating Dominis and his staff officers were recalled for economic reasons and the Military Act of 1886 was later declared unconstitutional.[100][97] The Military Act of 1888 was passed reducing the size of the army to four volunteer companies: the Honolulu Rifles, the King's Own, the Queen's Own, the Prince's Own, and the Leleiohoku Guard. In 1890, another military act further restricted the army to just the King's Royal Guards.[101][102][103]

Polynesian confederation[edit]

The idea of Hawaii's involvement in the internal affairs of Polynesian nations had been around at least two decades before Kalākaua's election, when Australian Charles St Julian volunteered to be a political liaison to Hawaii in 1853. He accomplished nothing of any significance.[104] Kalākaua's interest in forming a Polynesian coalition, with him at the head, was influenced by both Walter M. Gibson and Italian soldier of fortune Celso Caesar Moreno. In 1879 Moreno urged the king to create such a realm with Hawaii at the top of the empire by " ... uniting under your sceptre the whole Polynesian race and make Honolulu a monarchical Washington, where the representatives of all the islands would convene in Congress."[105]

In response to the activities of Germany and Great Britain in Oceania, Gibson's Pacific Commercial Advertiser urged Hawaii's involvement in protecting the island nations from international aggression.[106] Gibson was appointed to Kalākaua's cabinet as Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1882.[107] In 1883, he introduced the approved legislation to convey in writing to foreign governments that Hawaii fully supported the independence of Polynesian nations. The subsequent "Hawaiian protest" letter he drafted was mostly ignored by nations that received it.[108] The Daily Bulletin in Honolulu issued its own response, "Hawaii's true policy is to confine her attention to herself, ...".[109] The Hawaiian Gazette criticized Gibson's character and mockingly referred to the proposed venture as the "Empire of the Calabash".[110]

In 1885, Gibson dispatched Minister to the United States Henry A. P. Carter to Washington D. C. and Europe to convey Hawaii's intentions towards Polynesia. Carter made little headway with Gibson's instructions. He pushed for direct intervention into a political upheaval in Samoa, where the German Empire backed rebels under their leader Tamasese in an attempt to overthrow King Malietoa Laupepa.[111] In an effort to keep him in power, Gibson convinced the 1886 legislature to allocate $100,000 to purchase the steamship Zealandia, $50,000 for its operating expenses, and $35,000 for foreign missions. United States special commissioner to Samoa, George H. Bates advised Kalākaua that Hawaii should mind its own business and stay out of Samoan affairs. Instead, Hawaii sent a delegation headed by John E. Bush to Samoa, where Samoan King Malietoa Laupepa signed a Samoan-Hawaiian confederation treaty on February 17, 1887.[112] Bush also presented Malietoa with the Royal Order of the Star of Oceania, which Kalakaua had created to honor the monarchs and chiefs of the Polynesian confederation. The government sent HHMS Kaimiloa for Bush's use in visiting the chiefs of the other islands of Polynesia.[98]

The United States and Great Britain joined with Germany in expressing their disapproval of the treaty. Germany warned the United States and Great Britain, "In case Hawaii ... should try to interfere in favor of Malietoa, the King of the Sandwich Islands would thereby enter into [a] state of war with us." When German warships arrived in Samoan waters, Malietoa surrendered and was sent into exile. The Kaimiloa and Bush's delegation were recalled to Honolulu after the ousting of the Gibson administration.[113] Kalākaua's later explanation of Hawaii's interference in Samoa was, "Our Mission was simply a Mission of phylanthropy [sic] more than any thing, but the arogance [sic] of the Germans prevented our good intentions and . . . we had to withdraw the Mission."[114]

1887 Bayonet Constitution[edit]

In Memoirs of the Hawaiian Revolution, Sanford B. Dole devoted a chapter to the Bayonet Constitution. He stated that King Kalākaua appointed cabinet members not for their ability to do the job, but for their ability to bend to his will. Consequently, according to Dole, appropriated funds were shifted from one account to another, "for fantastic enterprises and for the personal aggrandizement of the royal family."[115] Dole placed much of the blame on Gibson, and accused Kalākaua of taking a bribe of $71,000 from Tong Kee to grant an opium license, an action done via one of the king's political allies Junius Kaʻae.[116][117]

Despite his own personal opposition, Kalakaua signed a legislative bill in 1886 creating a single opium vending and distribution license.[118][119] Kaʻae had suggested to rice planter Tong Kee, also known as Aki, that a monetary gift to the king might help him acquire it. Aki took the suggestion and gave thousands of dollars to the king.[120][121] Another merchant, Chun Lung, made the government an offer of $80,000.00 which forced Aki to raise even more cash.[122][123] The license was eventually awarded to Chun who withheld his payment until the license was actually signed over to him on December 31, 1886. Kalākaua admitted that he had been overruled by his cabinet who were friendly with Chun.[124] After the reform party took control of the government, the opium license debt remained unpaid. Kalākaua agreed to make restitution for his debts via revenues from the Crown Lands. However, other liabilities and outstanding debt forced him to sign his debt over to trustees who would control all of Kalākaua's private estates and Crown Land revenues.[125][126] When trustees refused to add the opium debt, Aki sued. Although the court ruled, "The king could do no wrong", the trustees were found liable for the debt.[125]

The Hawaiian League was formed to change the status quo of government "by all means necessary",[127] and had joined forces with the Honolulu Rifles militia group. Anticipating a coup d'état, the king took measures to save himself by dismissing Gibson and his entire cabinet on June 28.[127] Fearing an assassination was not out of the question, Kalākaua barricaded himself inside the palace. The Hawaiian League presented a June 30 resolution demanding the king's restitution for the alleged bribe. Also known as the "committee of thirteen", it was composed of: Paul Isenberg, William W. Hall, James A. Kennedy, William Hyde Rice, Captain James A. King, E. B. Thomas, H. C. Reed, John Mark Vivas, W. P. A. Brewer, Rev. W. B. Oleson, Cecil Brown, Captain George Ross and Joseph Ballard Atherton.[128]

The newly appointed cabinet members were William Lowthian Green as prime minister and minister of finance, Clarence W. Ashford as attorney general, Lorrin A. Thurston as minister of the interior, and Godfrey Brown as minister of foreign affairs.[129]

A new constitution was drafted immediately by the Hawaiian Committee and presented to Kalākaua for his signature on July 6. The next day he issued a proclamation of the abrogation of the 1864 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii.[130] The new constitution was nicknamed the Bayonet Constitution because of the duress under which it was signed. His sister Liliuokalani stated in Hawaii's Story that her brother was convinced that if he did not sign, he would be assassinated. She wrote that he no longer knew who was friend or foe. He felt betrayed by people he once trusted and had told her that everywhere he went he was under constant surveillance.[131]

It has been known ever since that day as "The Bayonet Constitution," and the name is well chosen; for the cruel treatment received by the king from the military companies, which had been organized by his enemies under other pretences, but really to give them the power of coercion, was the chief measure used to enforce his submission.

— Liliʻuokalani[131]

The Bayonet Constitution allowed the King to appoint his cabinet but placed that cabinet under the sole authority of the legislature. It required any executive actions of the monarch to be approved by the cabinet. Previous suffrage (voting rights) was restricted to male subjects of the kingdom regardless of race. The new constitution restricted suffrage only to Hawaiian, American or European men residing in Hawaii, if they were 21 years old, literate with no back unpaid taxes, and would take an oath to support the law of the land. By placing a new minimum qualifier of $3,000 in property ownership and a minimum income of $600 for voters of the House of Nobles, the new constitution disqualified many poor Native Hawaiians from voting for half of the legislature. Naturalized Asians were deprived of the vote for both houses of the legislature.[132][133]

Gibson was arrested on July 1 and charged with embezzlement of public funds. The case was soon dropped for lack of evidence. Gibson fled to California on July 12, and died there 6 months later on January 21, 1888.[134]

When the new constitution went into effect, state-sponsored students studying abroad were recalled. One of those was Robert William Wilcox who had been sent to Italy for military training. Wilcox's initial reaction to the turn of events was advocating Liliuokalani be installed as Regent. On July 30, 1889, however, he and Robert Napuʻuako Boyd, another state-sponsored student, led a rebellion aimed at restoring the 1864 constitution, and, thereby, the king's power. Kalākaua, possibly fearing Wilcox intended to force him to abdicate in favor of his sister, was not in the palace when the insurrection happened. The government's military defense led to the surrender of the Wilcox's insurgents.[135]

Death and succession[edit]

Kalākaua sailed for California aboard the USS Charleston on November 25, 1890. Accompanying him were his trusted friends George W. Macfarlane and Robert Hoapili Baker. There was uncertainty about the purpose of the king's trip. Minister of Foreign Affairs John Adams Cummins reported the trip was solely for the king's health and would not extend beyond California. Local newspapers and British commissioner Wodehouse worried the king might go farther east to Washington, DC, to negotiate a continued cession of Pearl Harbor to the United States after the expiration of the reciprocity treaty or possible annexation of the kingdom. His sister Liliʻuokalani, after unsuccessfully dissuading him from departing, wrote he meant to discuss the McKinley Tariff with the Hawaiian ambassador to the United States Henry A. P. Carter in Washington. She was again appointed to serve as regent during his absence.[136]

Upon arriving in California, the party landed in San Francisco on December 5. Kalākaua, whose health had been declining, stayed in a suite at the Palace Hotel.[137] Traveling throughout Southern California and Northern Mexico, he suffered a minor stroke in Santa Barbara and was rushed back to San Francisco. He was placed under the care of George W. Woods, surgeon of the United States Pacific Fleet. Against the advice of Dr. Woods, Kalākaua insisted on going to his initiation at the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (A.A.O.N.M.S.) on January 14. He was given a tonic of Vin Mariani that got him on his feet, and was accompanied to the rites by an escort from the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. The ceremonies did not take long, and he was returned to his suite within an hour.[138] Two days before his death, he lapsed into a coma. Kalākaua died at 2:35 pm on Tuesday, January 20, 1891.[139] US Navy officials listed the official cause of death as Bright's Disease (inflammation of the kidneys).[140]

His last words were, "Aue, he kanaka au, eia i loko o ke kukonukonu o ka maʻi!," or "Alas, I am a man who is seriously ill." The more popular quote, "Tell my people I tried", attributed as his last words, was actually invented by novelist Eugene Burns in his 1952 biography of Kalākaua, The Last King of Paradise.[141] Shortly before his death, his voice was recorded on a phonograph cylinder, which is now in the Bernice P. Bishop Museum.[142]

The news of Kalākaua's death did not reach Hawaii until January 29 when the Charleston returned to Honolulu with the king's remains.[143] As his designated heir-apparent,[50] Liliuokalani ascended to the throne the same day.[144]

After a state funeral in California and a second one in Honolulu, the king's remains were buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Mauna ʻAla on February 15, 1891.[145][146] In a ceremony officiated by his sister Liliʻuokalani on June 24, 1910, his remains, and those of his family, were transferred to the underground Kalākaua Crypt after the main mausoleum building had been converted into a chapel.[147][148]

Legacy[edit]

Kalākaua's reign is generally regarded as the first Hawaiian Renaissance, for both his influence on Hawaii's music, and for other contributions he made to reinvigorate Hawaiian culture. His actions inspired the reawakening Hawaiian pride and nationalism for the kingdom.[149][150]

During the earlier reign of Christian convert Kaʻahumanu, dancing the hula was forbidden and punishable by law. Subsequent monarchs gradually began allowing the hula, but it was Kalākaua who brought it back in full force. Chants, meles and the hula were part of the official entertainment at Kalākaua's coronation and his birthday jubilee. He issued an invitation to all Hawaiians with knowledge of the old meles and chants to participate in the coronation, and arranged for musicologist A. Marques to observe the celebrations.[151] Kalākaua's cultural legacy lives on in the Merrie Monarch Festival, a large-scale annual hula competition in Hilo, Hawaii, begun in 1964 and named in his honor.[152][153] A composer of the ancient chants or mele, for the first time Kalākaua published a written version of the Kumulipo, a 2,102-line chant that had traditionally been passed down orally. It traces the royal lineage and the creation of the cosmos.[154] He is also known to have revived the Hawaiian martial art of Lua, and surfing.[155]

The Hawaiian Board of Health (different from the governmental Board of Health) passed by the 1886 legislature consisted of five Native Hawaiians, appointed by Kalākaua, who oversaw the licensing and regulation of the traditional practice of native healing arts.[156] He also appointed Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina as the first Native Hawaiian curator of the Hawaiian National Museum and increased funding for the institution.[150]

In 1886, Kalākaua had his Privy Council license the ancient Hale Nauā Society for persons of Hawaiian ancestry. The original Hale Naua had not been active since Kamehameha I, when it had functioned as a genealogical research organization for claims of royal lineage. When Kalākaua reactivated it, he expanded its purpose to encompass Hawaiian culture as well as modern-day arts and sciences and included women as equals. The ranks of the society grew to more than 200 members, and was a political support for Kalākaua that lasted until his death in 1891.[157] In 2004, the National Museum of Natural History displayed Kalākaua's red-and-yellow feathered Hale Naua ʻahuʻula and feathered kāhili as part of its Hawaiian special exhibit.[158]

Kalākaua's sponsorship of and a brief career in the Hawaiian language press gave him the additional epithet of the "Editor King". From 1861 to 1863, Kalākaua with G. W. Mila, J. W. H. Kauwahi and John K. Kaunamano co-edited Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika (The Star of the Pacific), the first Hawaiian language newspaper solely written by Native Hawaiians without the influence of American missionaries. This nationalist paper focused on Hawaiian topics especially traditional folklore and poetry.[159][160] In 1870 he also edited the daily newspaper Ka Manawa (Times), which concerned itself with international news, local news and genealogies but only lasted for two months.[159][161] He also sponsored the literary journal, Ka Hoku o Ke Kai (The Star of the Sea), which ran from 1883 to 1884.[162]

The Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame honored Kalākaua and his brother and sisters as Na Lani ʻEhā ("The Heavenly Four") for their patronage and enrichment of Hawaii's musical culture and history.[152][163] "Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī" was officially designated the Hawaii state anthem in 1967. Originally titled "Hymn to Kamehameha I", Henri Berger, leader of the Royal Hawaiian Band, wrote the instrumental melody in 1872, influenced by the Prussian anthem "Heil dir im Siegerkranz". Kalākaua added the lyrics in 1874, and the Kawaiahaʻo Church Choir sang it on his birthday that year. In 1876, it became the official anthem of the Kingdom of Hawaii until the overthrow of the monarchy.[164] Other works by the king include "Sweet Lei Lehua", "ʻAkahi Hoʻi", "E Nihi Ka Hele", "Ka Momi", and "Koni Au I Ka Wai". Seven of his songs were published in Ka Buke O Na Leo Mele Hawaii (1888) using the pseudonym "Figgs". He generally wrote only the lyrics for most of his surviving works.[165]

He established diplomatic relations with the Kingdom of Serbia[166] and was awarded the Order of Cross of Takovo.[167]

The ukulele was introduced to the Hawaiian islands during the reign of Kalākaua, by Manuel Nunes, José do Espírito Santo, and Augusto Dias, Portuguese immigrants from Madeira and Cape Verde.[168] The king became proficient on the instrument. According to American journalist Mary Hannah Krout and Hawaii resident Isobel Osbourne Strong, wife of artist Joseph Dwight Strong and stepdaughter of Robert Louis Stevenson, he would often play the ukulele and perform meles for his visitors, accompanied by his personal musical group Kalākaua's Singing Boys (aka King's Singing Boys). Strong recalled the Singing Boys as "the best singers and performers on the ukulele and guitar in the whole islands".[169] Kalākaua was inducted into the Ukulele Hall of Fame in 1997.[170]

Kalākaua Avenue was created in March 1905 by the House and Senate of the Hawaii Territorial Legislature. It renamed the highway known as Waikiki Road, "to commemorate the name of his late Majesty Kalākaua, during whose reign Hawaii made great advancement in material prosperity".[171]

The King David Kalakaua Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975 under its former name U.S. Post Office, Customhouse, and Courthouse. Located at 335 Merchant Street in Honolulu, it was once the official seat of administration for the Territory of Hawaii. The building was renamed for Kalākaua in 2003.[172]

In 1985, a bronze statue of Kalākaua was donated to the City and County of Honolulu to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese laborers after the king's visit to Japan.[173] It was commissioned by the Oahu Kanyaku Imin Centennial Committee on behalf of the Japanese-American community of Hawaii. The statue was designed and created by musician Palani Vaughan, architect Leland Onekea and Native Hawaiian sculptor Sean Kekamakupaa Kaonohiokalani Lee Loy Browne. It is located at the corner of Kalakaua and Kuhio avenues in Waikiki.[174]

A Hawaiian song about Kalākaua can be heard in the Disney movie Lilo & Stitch when Lilo is introduced in the movie. The mele was written as a mele inoa, its original title being "He Inoa No Kalani Kalākaua Kulele" (a namesong for the chief, Kalākaua). On the Lilo & Stitch soundtrack, it was retitled as "He Mele No Lilo".[175]

Notable published works[edit]

- Na Mele Aimoku, Na Mele Kupuna, a Me Na Mele Ponoi O Ka Moi Kalākaua I. Dynastic Chants, Ancestral Chants, and Personal Chants of King Kalākaua I. (1886). Hawaiian Historical Society, Honolulu, 2001.[176]

- The Legends and Myths of Hawaii: The Fables and Folk-lore of a Strange People. (1888). C.E. Tuttle Company, New York, 1990.[177]

Honours[edit]

Kingdom of Hawaii:

Kingdom of Hawaii:- Companion of the Order of Kamehameha I, 1867

- Founder of the Order of Kalākaua, 28 September 1874[178]

- Founder of the Order of Kapiolani, 30 August 1880[179]

- Founder of the Order of the Star of Oceania, 16 December 1886[180]

Austria-Hungary: Commander of the Order of Franz Joseph, 1871;[181] Grand Cross, 1874[182]

Austria-Hungary: Commander of the Order of Franz Joseph, 1871;[181] Grand Cross, 1874[182] Denmark: Grand Cross of the Dannebrog, 11 March 1880[183]

Denmark: Grand Cross of the Dannebrog, 11 March 1880[183]- Sweden-Norway: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of Vasa, 18 February 1881[184]

Empire of Japan: Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, 14 March 1881[185]

Empire of Japan: Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum, 14 March 1881[185] Siam: Grand Cross of the Crown of Siam, April 1881[186]

Siam: Grand Cross of the Crown of Siam, April 1881[186] United Kingdom: Honorary Grand Cross of St Michael and St George, 28 July 1881[187]

United Kingdom: Honorary Grand Cross of St Michael and St George, 28 July 1881[187] Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, August 1881[188]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, August 1881[188] Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa, 19 August 1881[185]

Kingdom of Portugal: Grand Cross of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa, 19 August 1881[185] Kingdom of Serbia:[189]

Kingdom of Serbia:[189]- Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo, 28 June 1883

- Grand Cross of St. Sava, 28 June 1883

Ancestry[edit]

| Ancestors of Kalākaua | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Key- (k)= Kane (male/husband)

Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also[edit]

- Coins of the Hawaiian dollar

- Kalākaua's Cabinet Ministers

- Kalākaua's Privy Council of State

- Kalākaua's 1881 world tour

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Forbes 2003, p. 404.

- ^ a b "Crowned! Kalakaua's Coronation Accomplished: A Large But Unenthusiatic Assemblage!". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. February 14, 1883. LCCN sn83025121. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ a b c d Biographical Sketch 1884, pp. 72–74.

- ^ a b c Allen 1995, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 1–2, 104–105, 399–409; Allen 1982, pp. 33–36; Haley 2014, p. 96

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 104–105; Kuykendall 1967, p. 262; Osorio 2002, p. 201; Van Dyke 2008, p. 96

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 399.

- ^ Supreme Court of Hawaii (1866). In The Matter Of The Estate Of L. H. Kaniu, Deceased. Reports of a Portion of the Decisions Rendered by the Supreme Court of the Hawaiian Islands in Law, Equity, Admiralty, and Probate: 1857–1865. Honolulu: Government Press. pp. 82–86. OCLC 29559942. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Dibble 1843, p. 330.

- ^ "CALENDAR: Princes and Chiefs eligible to be Rulers". The Polynesian. 1 (9). Honolulu. July 20, 1844. p. 1, col. 3. Archived from the original on March 11, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.; Cooke & Cooke 1937, pp. v–vi; Van Dyke 2008, p. 364

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 5–9; Allen 1982, pp. 45–46

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zambucka 2002, pp. 5–10.

- ^ Cooke & Cooke 1937, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Gutmanis 1974, p. 144.

- ^ a b Allen 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Haley 2014, p. 100.

- ^ Allen 1995, pp. 23–24.

- ^ "Chief Justice Allen resigns, Harris appointed to take his place". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser at Newspapers.com. February 3, 1877. OCLC 8807872. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Allen 1982, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Damon, Samuel C. (February 1, 1876). "The Kings of Hawaii". The Friend. 25 (2). Honolulu: Samuel C. Damon. pp. 9–12. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ "By Authority". The Polynesian. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 5, 1853. LCCN sn82015408. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Allen 1995, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b "H. R. H. Prince L. Kamehameha at Victoria, Vancouver's Island". Polynesian at Newspapers.com. November 3, 1860. p. 2. OCLC 8807758. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Baur 1922, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Zambucka 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Hawaii & Lydecker 1918, pp. 76, 81, 86, 103, 109, 113, 117, 121, 124

- ^ "Appropriation Bill for 1858–1859". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. May 12, 1859. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on May 28, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Postmaster General – office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Chamberlain – office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Twain 1938, p. 105.

- ^ Allen 1995, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 12–15.

- ^ Zambucka 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Kuykendall 1953, pp. 3, 239

- ^ Kuykendall 1953, p. 243

- ^ Tsai 2016, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Kuykendall 1953, p. 245

- ^ a b c Kuykendall 1967, p. 4

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 6

- ^ a b Dabagh, Lyons & Hitchcock 1974, pp. 1–16

- ^ a b Kuykendall 1953, pp. 259–260; Allen 1982, pp. 131–132; Pogány 1963, pp. 53–61

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 5

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 245

- ^ Van Dyke 2008, p. 93

- ^ Kam 2017, p. 95 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKam2017 (help)

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 8

- ^ a b Kuykendall 1967, p. 9

- ^ Rossi 2013, pp. 103–107. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRossi2013 (help)

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 12

- ^ a b "The Heir Apparent". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. XXI (42). Honolulu. April 14, 1877. p. 2. OCLC 8807872. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Tsai 2014, pp. 115–143.

- ^ "King Kalakaua". Evening Star. Washington D. C. December 12, 1874. LCCN sn83045462. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; Monkman, Betty C. "The White House State Dinner". The White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ MacLennan 2014, pp. 224–228

- ^ Medcalf & Russell 1991, p. 5

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 59–62

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 396–397; "The New Hawaiian Treaty". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. May 15, 1886. LCCN sn85047084. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 83–84

- ^ "Hawaiian Legislature: Department of Foreign Affairs". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. June 10, 1882. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "The Legislature". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. July 1, 1884. LCCN sn82016412. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "Resolutions". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. September 28, 1886. LCCN sn85047084. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Quigg 1988, pp. 170–208

- ^ "The King's Tour Round the World: Portugal, Spain, Scotland, England, Paris. etc". Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands: The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. October 29, 1881. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Proclamation". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. February 12, 1881. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 228–230; "The King's Tour Around the World: Last Days in Japan". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. June 11, 1881. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 232

- ^ "The King's Tour Round the World: Additional Particulars of the Royal Visit to Spain and Portugal". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. October 15, 1881. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "A Royal Visitor". Evening Star. Washington, D. C. September 28, 1881. LCCN sn83045462. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Kalakaua Visits Edison: The King in Search of a Means to Light Up Honolulu". The Sun. New York, NY. September 26, 1881. LCCN sn83030272. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "King Kalakaua's Movements – His Majesty Examines The Edison Electric Light" (PDF). The New York Times. New York. September 26, 1881. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ "News of the Week". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. June 10, 1882. LCCN sn83045462. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "The Japanese". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. February 10, 1885. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved January 14, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; Thrum 1896, pp. 122–123

- ^ Thrum 1883, p. 12

- ^ Kalakaua 1971, pp. 90–91, 96

- ^ Staton, Ron. "Oahu: The Iolani, America's only royal palace". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c "ʻIolani Palace NRHP Asset Details". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Legislative Jottings". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. July 20, 1878. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kamins & Adler 1984, p. 103; Thrum 1881, p. 52

- ^ "Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "(Translation from the Hawaiian) Address by His Excellency John M. Kapena, Minister of Foreign Relations". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. January 3, 1880. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ a b "The New Palace". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. January 3, 1880. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 262; "Grand Masonic Banquet". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. December 30, 1882. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2016 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Electric Light at Palace Square". Honolulu Advertiser at Newspapers.com. July 22, 1886. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 97.

- ^ "An Act". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. August 4, 1880. LCCN sn83025121. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "That Coronation, A Religious Duty – Gibson's Reciprocity Policy-Favorism at Public Expense-Truth Shall Prevail". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. October 10, 1882. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; The Pacific Commercial Advertiser 1883, pp. 1–19

- ^ a b c Kuykendall 1967, pp. 259, 261–265

- ^ a b "Postponed Pleasures". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. February 21, 1883. LCCN sn83025121. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kamins & Adler 1984, p. 9; Wharton 2012, pp. 16–49

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 87

- ^ Medcalf & Russell 1991, pp. 5, 38–39

- ^ Andrade 1977, pp. 97–99

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 82

- ^ Andrade 1977, pp. 101–107

- ^ "The Legislature". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. September 22, 1886. LCCN sn85047084. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Local News". The Daily Herald. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 3, 1886. LCCN sn85047239. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "His Majesty's Jubilee Birthday". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 17, 1886. LCCN sn82016412. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ "Festivities of the First and Second Days". The Daily Herald. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 18, 1886. LCCN sn85047239. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "The Luau". The Daily Daily Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 23, 1886. LCCN sn82016412. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; "The Jubilee Ball". The Daily Herald. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 25, 1886. LCCN sn85047239. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 340–341

- ^ Harper's 1891

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 13; "General Order No. 1". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 28, 1874. p. 1. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Newbury 2001, p. 22; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 350–352; "Army Commissions office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Chapter XXII: Act Act To Organize The Military Forces Of The Kingdom. Laws of His Majesty Kalakaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands: Passed by the Legislative Assembly at Its Session of 1886. Honolulu: Black & Auld. 1886. pp. 37–41. OCLC 42350849. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Adler 1965, pp. 7–21; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 327, 334–337

- ^ "Navy, Royal Hawaiian – Commissions office record" (PDF). state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 403–404.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 410–411, 421, 465–466.

- ^ Chapter XXV: An Act Relating To The Military Forces Of The Kingdom. Laws of His Majesty Kalakaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands: Passed by the Legislative Assembly at Its Session of 1888. Honolulu: Black & Auld. 1888. pp. 55–60. OCLC 42350849. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Chapter LII: An Act To Provide For A Military Force To Be Designated As 'The King's Royal Guard'. Laws of His Majesty Kalakaua, King of the Hawaiian Islands: Passed by the Legislative Assembly at Its Session of 1890. Honolulu: Black & Auld. 1890. pp. 107–109. OCLC 42350849. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 305–308

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 311–312

- ^ "Hawaiian Primacy in Polynesia". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. November 19, 1881. LCCN sn82015418. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 143

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 315–316

- ^ "The "Bulletin's" Protest". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. September 7, 1883. LCCN sn82016412. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Adler 1965, p. 8

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 322

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 324–329; "Polynesian Dominion Proclamation". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. March 30, 1887. OCLC 8807872. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 337–338

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 339

- ^ Dole 1936, p. 44

- ^ Dole 1936, p. 49

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 353, 360

- ^ Alexander 1896, p. 19.

- ^ Alexander 1894, p. 27.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 353, 360; Dye 1997, pp. 208–216; Forbes 2003, p. 290; Dole 1936, p. 49

- ^ Haley 2014, p. 265.

- ^ Zambucka 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Daws 1968, p. 245.

- ^ Dye 1997, p. 209.

- ^ a b Krout 1898, p. 7.

- ^ Forbes 2003, p. 290.

- ^ a b Van Dyke 2008, p. 121

- ^ "Mass Meeting". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. June 30, 1887. LCCN sn82016412. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2018 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Van Dyke 2008, pp. 121–122

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 366–372

- ^ a b Liliuokalani 1898, p. 181

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 368–372

- ^ MacLennan 2014, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 365–366

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 424–430

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 470–474; Allen 1982, pp. 225–226; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 206–207

- ^ Rego, Nilda (April 25, 2013). "Days Gone By: 1890: Hawaii's King Kalakaua visits San Francisco". The Mercury News. San Francisco. OCLC 723850972. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ Karpiel 2000, pp. 392–393

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, p. 472

- ^ Dando-Collins 2014, p. 42; Mcdermott, Choy & Guerrero 2015, p. 59;Carl Nolte (August 22, 2009). "S.F.'s (New) Palace Hotel Celebrates a Century". San Francisco Chronicle. OCLC 66652554. Archived from the original on September 27, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2010.

- ^ Thompson, David (February 2013). "Kalakaua's Famous Last Words?". Honolulu Magazine. OCLC 180851733. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ^ "Bishop Museum Tries To Revive Past King's Voice". Kitv.com. November 24, 2009. OCLC 849807032. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 473–474; Kam 2017, pp. 127–130 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKam2017 (help)

- ^ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 473–474

- ^ Kam 2017, pp. 127–130. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKam2017 (help)

- ^ Parker 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Parker 2008, pp. 15, 39.

- ^ "The Weird Ceremonial of Monarchial Times Marked Transfer of Kalakaua Dynasty Dead to Tomb". The Hawaiian Gazette. Honolulu. June 28, 1910. p. 2. LCCN sn83025121. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Zambucka 2002, pp. 63–65; Vowell 2011, p. 84; Kanahele, George (July 1979). "Hawaiian Renaissance Grips, Changes Island History". Haʻilono Mele. 5 (7). Honolulu: The Hawaiian Music Foundation. pp. 1–9. LCCN no99033299. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Williams, Ronald, Jr. (January 2015). "The Other Hawaiian Renaissance". Hana Hou!. 17 (6). Honolulu. OCLC 262477335. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

- ^ Buck 1994, pp. 108–111

- ^ a b "Patron of Hawaiian Music Culture: David Kalakaua (1836–1891)". Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Merrie Monarch Festival". eVols. University of Hawai'i at Manoa. hdl:10524/1440. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Zambucka 2002, pp. 63–65; Buck 1994, pp. 123–126

- ^ Foster 2014, p. 44

- ^ "An Act: To Regulate the Hawaiian Board of Health". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands. October 11, 1886. LCCN sn85047084. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017 – via Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- ^ Karpiel 1999