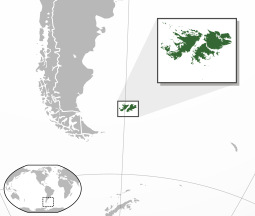

Координаты : 51 ° 41'S 59 ° 10'W. / 51.683°S 59.167°W

| Фолклендские острова | |

|---|---|

| Девиз : " Желай правды " | |

| Гимн : " Боже, храни королеву " | |

| Неофициальный гимн: « Песня Фолклендских островов ». | |

Расположение Фолклендских островов | |

| Суверенное государство | Великобритания |

| Первое поселение | 1764 |

| Британское правление восстановлено | 3 января 1833 г. |

| Фолклендская война | 2 апреля - 14 июня 1982 г. |

| Текущая конституция | 1 января 2009 г. |

| Столицаи крупнейшее поселение | Стэнли 51 ° 42' ю.ш. 57 ° 51'з.д. / 51.700°S 57.850°W |

| Официальные языки | английский |

| Демоним (ы) | Житель Фолклендских островов , житель Фолклендских островов |

| Правительство | Выделенная парламентская зависимость при конституционной монархии |

| • Монарх | Елизавета II |

| • Губернатор | Найджел Филлипс |

| • Главный исполнительный директор | Барри Роуленд |

| Законодательная власть | Законодательное собрание |

| Правительство Соединенного Королевства | |

| • Министр | Венди Мортон |

| Область | |

| • Общее | 12 200 км 2 (4700 квадратных миль) |

| • Воды (%) | 0 |

| Самая высокая высота | 2,313 футов (705 м) |

| Население | |

| • перепись 2016 г. | 3,398 [1] ( без рейтинга ) |

| • Плотность | 0,28 / км 2 (0,7 / кв. Миль) ( без рейтинга ) |

| ВВП ( ППС ) | Оценка на 2013 год |

| • Общее | 228,5 миллиона долларов [2] |

| • На душу населения | 96 962 долл. США ( 4-е место ) |

| Джини (2010) | 34,17 [3] средний · 64-й |

| ИЧР (2010 г.) | 0,874 [4] очень высокий · 20-й |

| Валюта | Фунт Фолклендских островов (£) ( FKP ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC-03: 00 ( FKST ) |

| Формат даты | дд / мм / гггг |

| Сторона вождения | оставил |

| Телефонный код | +500 |

| Почтовый индекс Великобритании | FIQQ 1ZZ |

| Код ISO 3166 | FK |

| Интернет-домен | .fk |

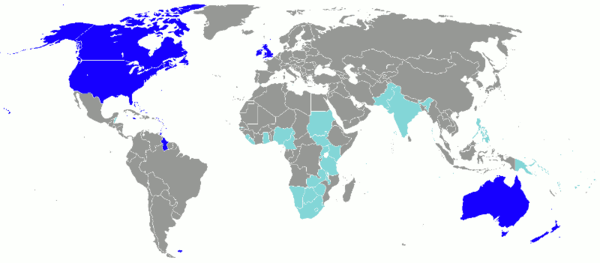

В Фолклендские ( / е ɔː л к л ə п д / ; испанский : Мальвинские , выраженной [Islas malβinas] ) представляет собой архипелаг в Южной Атлантике на Патагонском шельфе . Главные острова около 300 миль (483 км) к востоку от Южной Америки южного «s Патагонского побережья и около 752 миль (1,210 км) от северной оконечности на Антарктическом полуострове, на широте около 52 ° ю. Архипелаг площадью 4 700 квадратных миль (12 000 квадратных километров) включает Восточный Фолкленд , Западный Фолкленд и 776 более мелких островов. Как заморская территория Великобритании , Фолкленды обладают внутренним самоуправлением , и Соединенное Королевство берет на себя ответственность за их оборону и иностранные дела. Столица и крупнейшее поселение - Стэнли на Восточном Фолкленде.

Споры существуют по поводу открытия Фолклендов и последующей их колонизации европейцами. В разное время на островах были поселения французов, англичан, испанцев и аргентинцев. Великобритания восстановила свое правление в 1833 году , но Аргентина сохраняет свои права на острова . В апреле 1982 года аргентинские вооруженные силы вторглись на острова . Британская администрация была восстановлена через два месяца после окончания Фолклендской войны . Почти все жители Фолклендских островов выступают за то, чтобы архипелаг оставался заморской территорией Великобритании. Его статус суверенитета является частью продолжающегося спора между Аргентиной и Соединенным Королевством .

Население (3398 жителей в 2016 году) [1] состоит в основном из коренных жителей Фолклендских островов , большинство из которых имеют британское происхождение. Другие этнические группы включают французов, гибралтарцев и скандинавов. Иммиграция из Соединенного Королевства, острова Святой Елены в Южной Атлантике и Чили обратила вспять сокращение населения. Преобладающий (и официальный) язык - английский. В соответствии с Законом о британском гражданстве (Фолклендские острова) 1983 года жители Фолклендских островов являются британскими гражданами .

Острова лежат на границе субантарктических океанических и тундровых климатических зон, и оба основных острова имеют горные хребты, достигающие 2300 футов (700 м). Они являются домом для больших популяций птиц, хотя многие из них больше не размножаются на основных островах из-за хищничества со стороны интродуцированных видов . Основные виды экономической деятельности включают рыболовство, туризм и овцеводство с упором на экспорт высококачественной шерсти. Разведка нефти, лицензированная правительством Фолклендских островов , остается спорной из-за морских споров с Аргентиной.

Этимология

Название «Фолклендские острова» происходит от Фолклендских звука , тем проливом , который отделяет два главных острова. [5] Название «Фолкленд» было применено к каналу Джоном Стронгом , капитаном английской экспедиции, высадившейся на островах в 1690 году. Стронг назвал пролив в честь Энтони Кэри, 5-го виконта Фолкленда , казначея военно-морского флота. кто спонсировал его путешествие. [6] Титул виконта происходит от города Фолкленд , Шотландия - название города, вероятно, происходит от гэльского термина, относящегося к «ограждению» ( ланн ), [A]но менее правдоподобно это могло быть от англосаксонского термина « народная страна» (земля, принадлежащая праву народа ). [8] Название «Фолкленды» не был применен к островам до 1765 года , когда британский капитан Джон Байрон из королевского флота утверждал их короля Георга III , как «Фолклендских островов в». [9] Термин «Фолклендские острова» - это стандартное сокращение, используемое для обозначения островов.

Испанское название архипелага, Islas Malvinas , происходит от французского Îles Malouines - названия, данного островам французским исследователем Луи-Антуаном де Бугенвилем в 1764 году. [10] Бугенвиль, основавший первое поселение на островах, назвал этот район. после порта Сен-Мало (пункт отправления его кораблей и колонистов). [11] Порт, расположенный в регионе Бретань на западе Франции, был назван в честь Святого Мало (или Маклу), христианского евангелиста , основавшего город. [12]

На двадцатой сессии Генеральной Ассамблеи Организации Объединенных Наций , то Четвертый комитет определил , что во всех других языках , кроме испанского, вся документация ООН назначит территорию как Фолклендских (Мальвинских) островов . На испанском языке территория была обозначена как Islas Malvinas (Фолклендские острова) . [13] Номенклатура, используемая Организацией Объединенных Наций для целей статистической обработки, - это Фолклендские (Мальвинские) острова . [14]

История

Хотя огнеземельцы из Патагонии могли посещать Фолклендские острова в доисторические времена, [15] острова были необитаемыми, когда европейцы впервые их обнаружили. [16] Утверждения об открытии относятся к 16 веку, но нет единого мнения о том, открыли ли первые исследователи Фолклендские острова или другие острова в Южной Атлантике. [17] [18] [B] Первая бесспорная высадка на острова приписывается английскому капитану Джону Стронгу, который по пути в Перу и побережье Чили в 1690 году открыл Фолклендский пролив и заметил воду и дичь на островах. [20]

Фолклендские острова оставались необитаемыми до основания Порт-Луи на Восточном Фолкленде в 1764 году французским капитаном Луи Антуаном де Бугенвилем и основания Порт-Эгмонт на острове Сондерс в 1766 году британским капитаном Джоном Макбрайдом . [C] Были ли поселения осведомлены о существовании друг друга, это обсуждается историками. [23] В 1766 году Франция передала свои права на Фолклендские острова Испании, которая в следующем году переименовала французскую колонию в Пуэрто-Соледад . [24] Проблемы начались, когда Испания открыла и захватила Порт-Эгмонт в 1770 году. Войнаего едва удалось избежать из-за его реституции Британии в 1771 году [25].

И британские, и испанские поселения сосуществовали на архипелаге до 1774 года, когда новые экономические и стратегические соображения Британии вынудили ее добровольно уйти с островов, оставив мемориальную доску с заявлением о правах на Фолклендские острова королю Георгу III. [26] Наместничество Испании в Рио-де-ла-Плата стало единственным правительственным присутствием на территории. Западный Фолкленд остался заброшенным, а Пуэрто-Соледад превратился в лагерь для военнопленных. [27] На фоне британского вторжения в Рио-де-ла-Плата во время наполеоновских войн.в Европе губернатор островов эвакуировал архипелаг в 1806 году; Оставшийся колониальный гарнизон Испании последовал его примеру в 1811 году, за исключением гаучо и рыбаков, которые остались добровольно. [27]

После этого архипелаг посещали только рыболовецкие суда; его политический статус не оспаривался до 1820 года, когда полковник Дэвид Джуэтт , американский капер, работавший в Соединенных провинциях Рио-де-ла-Плата , сообщил стоящим на якоре кораблям о притязаниях Буэнос-Айреса на территории Испании в Южной Атлантике в 1816 году. [28] [D] Поскольку на островах не было постоянных жителей, в 1823 году Буэнос-Айрес предоставил немецкому торговцу Луису Верне разрешение на ведение рыбной ловли и разведение диких животных на архипелаге. [E]Верне поселился на руинах Пуэрто-Соледад в 1826 году и накапливал ресурсы на островах, пока предприятие не стало достаточно безопасным, чтобы привлечь поселенцев и сформировать постоянную колонию. [32] Буэнос-Айрес назначил Верне военным и гражданским командующим островов в 1829 году, [33] и он попытался регулировать тюлень, чтобы остановить деятельность иностранных китобоев и охотников на тюленей. [27] предприятие Vernet продлилось до спора по поводу рыбалки и охоты прав привели к налету по американскому военному кораблю USS Lexington в 1831 году, [34] [F] , когда ВМС США командующий Сайлас Дунканобъявил о роспуске правительства острова. [35]

Буэнос-Айрес попытался сохранить влияние на поселение, установив гарнизон, но в следующем году за восстанием 1832 года последовало прибытие британских войск, которые вновь подтвердили правление Великобритании . [36] Аргентинская конфедерация (во главе с Буэнос - Айрес губернатор Хуан Мануэль де Росас ) протестовали против действий Великобритании, [37] [G] и аргентинские правительства продолжали с тех пор зарегистрировать официальные протесты против Великобритании. [40] [H] Британские войска ушли после завершения своей миссии, оставив территорию без официального правительства. [42] Заместитель Верне, шотландец Мэтью БрисбенВ том же году вернулся на острова, чтобы восстановить бизнес, но его усилия прекратились после того, как, на фоне беспорядков в Порт-Луи, гаучо Антонио Риверо привел группу недовольных людей к убийству Брисбена и высших руководителей поселения; выжившие прятались в пещере на соседнем острове, пока британцы не вернулись и не восстановили порядок. [42] В 1840 году Фолклендские острова стали колонией короны, и шотландские поселенцы впоследствии основали официальную пасторальную общину. [43] Четыре года спустя почти все переехали в Порт-Джексон, который считался лучшим местом для правительства, и торговец Сэмюэл Лафон предпринял попытку поощрить британскую колонизацию. [44]

Стэнли , как вскоре был переименован Порт-Джексон, официально стал резиденцией правительства в 1845 году. [45] В начале своей истории Стэнли имел отрицательную репутацию из-за потерь при транспортировке грузов; только в экстренных случаях корабли, огибающие мыс Горн, останавливались в порту. [46] Тем не менее, географическое положение Фолклендских островов оказалось идеальным для ремонта судов и «торговли кораблекрушениями» - бизнеса по продаже и покупке затонувших кораблей и их грузов. [47] Помимо этой торговли, коммерческий интерес к архипелагу был минимальным из-за дешевой шкуры дикого скота, бродящего по пастбищам. Экономический рост начался только после того, как компания Фолклендских островов выкупила обанкротившееся предприятие Lafone в 1851 году.[I] успешно представил овец чевиот для выращивания шерсти, побудив другие фермы последовать его примеру. [49] Высокая стоимость импорта материалов в сочетании с нехваткой рабочей силы и, как следствие, высокой заработной платой означала, что судоремонтная торговля стала неконкурентоспособной. После 1870 года он пришел в упадок, поскольку замена парусных судов пароходами ускорилась из-за низкой стоимости угля в Южной Америке; к 1914 году, с открытием Панамского канала , торговля фактически прекратилась. [50] В 1881 году Фолклендские острова стали финансово независимыми от Великобритании. [45]Более века компания Фолклендских островов доминировала в торговле и занятости архипелага; кроме того, ей принадлежала большая часть жилья в Стэнли, который извлек большую выгоду из торговли шерстью с Великобританией. [49]

В первой половине 20 века Фолклендские острова играли важную роль в территориальных претензиях Великобритании на субантарктические острова и часть Антарктиды. Фолклендские острова управляли этими территориями как зависимыми Фолклендскими островами, начиная с 1908 года, и сохраняли их до своего роспуска в 1985 году. [51] Фолклендские острова также играли второстепенную роль в двух мировых войнах в качестве военной базы, способствовавшей контролю над Южной Атлантикой. В битве за Фолклендские острова во время Первой мировой войны в декабре 1914 года флот Королевского флота победил имперскую немецкую эскадру. Во время Второй мировой войны , после битвы на реке Плейт в декабре 1939 г., поврежденный в боях HMS Exeter отправился на Фолклендские острова для ремонта. [16] В 1942 году батальон, направлявшийся в Индию, был передислоцирован на Фолклендские острова в качестве гарнизона из-за опасений по поводу японского захвата архипелага. [52] После окончания войны на экономику Фолклендских островов повлияли снижение цен на шерсть и политическая неопределенность, возникшая в результате возобновления спора о суверенитете между Соединенным Королевством и Аргентиной. [46]

Напряжение между Великобританией и Аргентиной нарастало во второй половине века, когда президент Аргентины Хуан Перон утвердил суверенитет над архипелагом. [53] Спор о суверенитете обострился в 1960-х годах, вскоре после того, как Организация Объединенных Наций приняла резолюцию о деколонизации, которую Аргентина интерпретировала как благоприятную для ее позиции. [54] В 1965 году Генеральная Ассамблея ООН приняла Резолюцию 2065 , призывающую оба государства провести двусторонние переговоры для достижения мирного урегулирования спора. [54]С 1966 по 1968 год Великобритания конфиденциально обсуждала с Аргентиной передачу Фолклендов, предполагая, что ее решение будет принято островитянами. [55] Соглашение о торговых связях между архипелагом и материком было достигнуто в 1971 году, и, как следствие, Аргентина построила временный аэродром в Стэнли в 1972 году. [45] Тем не менее, Фолклендеры не согласны, что выражается их сильным лобби в парламенте Великобритании. и напряженность между Великобританией и Аргентиной фактически ограничивала переговоры о суверенитете до 1977 г. [56]

Обеспокоенная расходами на сохранение Фолклендских островов в эпоху урезания бюджета, Великобритания снова рассматривала возможность передачи суверенитета Аргентине в раннем правительстве Тэтчер . [57] Переговоры о суверенитете по существу снова закончились к 1981 году, и с течением времени спор обострился. [58] В апреле 1982 года началась Фолклендская война, когда аргентинские вооруженные силы вторглись на Фолкленды и другие британские территории в Южной Атлантике , ненадолго оккупировав их, пока британские экспедиционные силы не вернули эти территории в июне. [59] После войны Великобритания расширила свое военное присутствие, построивRAF Mount Pleasant и увеличение размера своего гарнизона. [60] Война также оставила около 117 минных полей, содержащих около 20 000 мин различных типов, включая противотранспортные и противопехотные мины. [61] Из-за большого количества жертв среди саперов первоначальные попытки разминирования прекратились в 1983 году. [61] [J] Операции по разминированию возобновились в 2009 году и были завершены в октябре 2020 года. [63]

Основываясь на рекомендациях лорда Шеклтона , Фолклендские острова перешли от монокультуры овец к экономике туризма и, с созданием исключительной экономической зоны Фолклендских островов , рыболовства. [64] [K] Дорожная сеть также была расширена, и строительство RAF Mount Pleasant позволило совершать дальние перелеты. [64] Также началась разведка нефти с указанием возможных коммерчески эксплуатируемых месторождений в бассейне Фолклендских островов. [65] Работы по разминированию возобновлены в 2009 году в соответствии с обязательствами Великобритании по Оттавскому договору и Саппер Хилл.Загон был очищен от мин в 2012 году, что позволило получить доступ к важной исторической достопримечательности впервые за 30 лет. [66] [67] Аргентина и Великобритания восстановили дипломатические отношения в 1990 году; С тех пор отношения ухудшились, поскольку ни один из них не согласовал условия будущих обсуждений суверенитета. [68] Споры между правительствами привели к тому, что «некоторые аналитики [] предсказывают рост конфликта интересов между Аргентиной и Великобританией ... из-за недавнего расширения рыбной промышленности в водах, окружающих Фолклендские острова». [69]

Правительство

Фолклендские острова - это самоуправляющаяся заморская территория Великобритании . [70] Согласно Конституции 2009 года , острова имеют полное внутреннее самоуправление; Великобритания отвечает за иностранные дела, сохраняя за собой право «защищать интересы Великобритании и обеспечивать хорошее управление территорией в целом ». [71] монарх Соединенного Королевства является главой государства и исполнительной власти осуществляется от имени монарха от губернатора , который назначает островов за главный исполнительный по рекомендации членов Законодательного собрания .[72] И губернатор, и глава исполнительной власти являются главой правительства . [73]

Губернатор Найджел Филлипс был назначен в сентябре 2017 года [74], а главный исполнительный директор Барри Роуленд был назначен в октябре 2016 года. [75] Министр Великобритании, ответственный за Фолклендские острова с 2019 года, Кристофер Пинчер руководит британской внешней политикой в отношении островов. [76]

Губернатор действует по рекомендации Исполнительного совета острова , состоящего из главы исполнительной власти, финансового директора и трех избранных членов Законодательного собрания (с губернатором в качестве председателя). [72] Законодательное собрание, однопалатный законодательный орган , состоит из главы исполнительной власти, финансового директора и восьми членов (пять из Стэнли и три из Кэмпа ), избираемых на четырехлетний срок всеобщим голосованием . [72] Все политики на Фолклендских островах независимы ; на островах нет политических партий. [77] После всеобщих выборов 2013 г., члены Законодательного собрания получили зарплату и, как ожидается, будут работать полный рабочий день и откажутся от всех ранее занимаемых рабочих мест или от деловых интересов. [78]

В качестве территории Соединенного Королевства, Фолклендские острова были частью заморских стран и территорий в Европейском Союзе до 2020 года . [79] Судебная система островов , находящаяся под контролем Министерства иностранных дел и по делам Содружества , в значительной степени основана на английском праве , [80] и конституция связывает территорию с принципами Европейской конвенции о правах человека . [71] Жители имеют право подавать апелляцию в Европейский суд по правам человека и Тайный совет . [81] [82] Правоохранительные органы находятся в веденииКоролевская полиция Фолклендских островов (RFIP) [80] и военная защита островов обеспечивается Соединенным Королевством. [83] Британский военный гарнизон дислоцируется на островах, а также правительственные фонды Фолклендские острова дополнительная компания -sized легкой пехоты ФОЛКЛЕНДСКИХ сил обороны . [84] Фолкленды претендуют на исключительную экономическую зону (ИЭЗ), простирающуюся на 200 морских миль (370 км) от их исходных береговых линий, в соответствии с Конвенцией Организации Объединенных Наций по морскому праву ; эта зона пересекается с ИЭЗ Аргентины. [85]

Суверенитет спор

Соединенное Королевство и Аргентина заявляют о суверенитете над Фолклендскими островами. Великобритания основывает свою позицию на непрерывном управлении островами с 1833 года и на «праве островитян на самоопределение, закрепленном в Уставе ООН ». [86] [87] [88] Аргентина утверждает, что, когда она достигла независимости в 1816 году, она приобрела Фолклендские острова у Испании. [89] [90] [91] случай 1833 является особенно спорным; Аргентина считает это доказательством "британской узурпации", тогда как Великобритания не принимает во внимание это как простое повторение своих требований. [92] [L]

В 2009 году премьер-министр Великобритании Гордон Браун встретился с президентом Аргентины Кристиной Фернандес де Киршнер и заявил, что никаких дальнейших переговоров о суверенитете Фолклендских островов не будет. [95] В марте 2013 года на Фолклендских островах был проведен референдум о своем политическом статусе: 99,8% поданных голосов высказались за то, чтобы остаться британской заморской территорией. [96] [97] Аргентина не признает жителей Фолклендских островов в качестве партнера по переговорам. [89] [98] [99]

География

Фолклендские острова имеют площадь 4 700 квадратных миль (12 000 км 2 ), а береговая линия оценивается в 800 миль (1300 км). [100] Архипелаг состоит из двух основных островов, Западных Фолклендов и Восточных Фолклендов, а также 776 небольших островов. [101] Острова преимущественно гористые и холмистые, [102] главным исключением являются депрессивные равнины Лафонии (полуостров, образующий южную часть Восточного Фолкленда). [103] Фолклендские острова состоят из фрагментов континентальной коры, образовавшихся в результате распада Гондваны и открытия Южной Атлантики, начавшегося 130 миллионов лет назад. Острова расположены вSouth Atlantic Ocean, on the Patagonian Shelf, about 300 miles (480 km) east of Patagonia in southern Argentina.[104]

The Falklands' approximate location is latitude 51°40′ – 53°00′ S and longitude 57°40′ – 62°00′ W.[105] The archipelago's two main islands are separated by the Falkland Sound,[106] and its deep coastal indentations form natural harbours.[107] East Falkland houses Stanley (the capital and largest settlement),[105] the UK military base at RAF Mount Pleasant, and the archipelago's highest point: Mount Usborne, at 2,313 feet (705 m).[106] Outside of these significant settlements is the area colloquially known as "Camp", which is derived from the Spanish term for countryside (Campo).[108]

The climate of the islands is cold, windy and humid maritime.[104] Variability of daily weather is typical throughout the archipelago.[109] Rainfall is common over half of the year, averaging 610 millimetres (24 in) in Stanley, and sporadic light snowfall occurs nearly all year.[102] The temperature has historically stayed between 21.1 and −11.1 °C (70.0 and 12.0 °F) in Stanley, with mean monthly temperatures varying from 9 °C (48 °F) early in the year to −1 °C (30 °F) in July.[109] Strong westerly winds and cloudy skies are common.[102] Although numerous storms are recorded each month, conditions are normally calm.[109]

Biodiversity

The Falkland Islands are biogeographically part of the Antarctic zone,[110] with strong connections to the flora and fauna of Patagonia in mainland South America.[111] Land birds make up most of the Falklands' avifauna; 63 species breed on the islands, including 16 endemic species.[112] There is also abundant arthropod diversity on the islands.[113] The Falklands' flora consists of 163 native vascular species.[114] The islands' only native terrestrial mammal, the warrah, was hunted to extinction by European settlers.[115]

The islands are frequented by marine mammals, such as the southern elephant seal and the South American fur seal, and various types of cetaceans; offshore islands house the rare striated caracara. There are also five different penguin species and a few of the largest albatross colonies on the planet.[116] Endemic fish around the islands are primarily from the genus Galaxias.[113] The Falklands are treeless and have a wind-resistant vegetation predominantly composed of a variety of dwarf shrubs.[117]

Virtually the entire land area of the islands is used as pasture for sheep.[118] Introduced species include reindeer, hares, rabbits, Patagonian foxes, brown rats and cats.[119] Several of these species have harmed native flora and fauna, so the government has tried to contain, remove or exterminate foxes, rabbits and rats. Endemic land animals have been the most affected by introduced species, and several bird species have been extirpated from the larger islands.[120] The extent of human impact on the Falklands is unclear, since there is little long-term data on habitat change.[111]

Economy

The economy of the Falkland Islands is ranked the 222nd largest out of 229 in the world by GDP (PPP), but ranks 5th worldwide by GDP (PPP) per capita.[122] The unemployment rate was 1% in 2016, and inflation was calculated at 1.4% in 2014.[118] Based on 2010 data, the islands have a high Human Development Index of 0.874[4] and a moderate Gini coefficient for income inequality of 34.17.[3] The local currency is the Falkland Islands pound, which is pegged to the British pound sterling.[123]

Economic development was advanced by ship resupplying and sheep farming for high-quality wool.[124] The main sheep breeds in the Falkland Islands are Polwarth and Corriedale.[125] During the 1980s, although ranch under-investment and the use of synthetic fibres damaged the sheep-farming sector, the government secured a major revenue stream by the establishment of an exclusive economic zone and the sale of fishing licences to "anybody wishing to fish within this zone".[126] Since the end of the Falklands War in 1982, the islands' economic activity has increasingly focused on oil field exploration and tourism.[127]

The port settlement of Stanley has regained the islands' economic focus, with an increase in population as workers migrate from Camp.[128] Fear of dependence on fishing licences and threats from overfishing, illegal fishing and fish market price fluctuations have increased interest in oil drilling as an alternative source of revenue; exploration efforts have yet to find "exploitable reserves".[121] Development projects in education and sports have been funded by the Falklands government, without aid from the United Kingdom.[126]

The primary sector of the economy accounts for most of the Falkland Islands' gross domestic product, with the fishing industry alone contributing between 50% and 60% of annual GDP; agriculture also contributes significantly to GDP and employs about a tenth of the population.[129] A little over a quarter of the workforce serves the Falkland Islands government, making it the archipelago's largest employer.[130] Tourism, part of the service economy, has been spurred by increased interest in Antarctic exploration and the creation of direct air links with the United Kingdom and South America.[131] Tourists, mostly cruise ship passengers, are attracted by the archipelago's wildlife and environment, as well as activities such as fishing and wreck diving; the majority find accommodation in Stanley.[132] The islands' major exports include wool, hides, venison, fish and squid; its main imports include fuel, building materials and clothing.[118]

Demographics

The Falkland Islands population is homogeneous, mostly descended from Scottish and Welsh immigrants who settled in the territory after 1833.[133] The Falkland-born population are also descended from English and French people, Gibraltarians, Scandinavians and South Americans. The 2016 census indicated that 43% of residents were born on the archipelago, with foreign-born residents assimilated into local culture. The legal term for the right of residence is "belonging to the islands".[134][135] In 1983, full British citizenship was given to Falkland Islanders under the British Nationality (Falkland Islands) Act.[133]

A significant population decline affected the archipelago in the twentieth century, with many young islanders moving overseas in search of education, a modern lifestyle, and better job opportunities,[136] particularly to the British city of Southampton, which came to be known in the islands as "Stanley North".[137] In recent years, the islands' population decline has reduced, thanks to immigrants from the United Kingdom, Saint Helena, and Chile.[138] In the 2012 census, a majority of residents listed their nationality as Falkland Islander (59 percent), followed by British (29 percent), Saint Helenian (9.8 percent), and Chilean (5.4 percent).[139] A small number of Argentines also live on the islands.[140]

The Falkland Islands have a low population density.[141] According to the 2012 census, the average daily population of the Falklands was 2,932, excluding military personnel serving in the archipelago and their dependents.[M] A 2012 report counted 1,300 uniformed personnel and 50 British Ministry of Defence civil servants present in the Falklands.[130] Stanley (with 2,121 residents) is the most-populous location on the archipelago, followed by Mount Pleasant (369 residents, primarily air-base contractors) and Camp (351 residents).[139] The islands' age distribution is skewed towards working age (20–60). Males outnumber females (53 to 47 percent), and this discrepancy is most prominent in the 20–60 age group.[134]

In the 2012 census, most islanders identified themselves as Christian (66 percent), followed by those with no religious affiliation (32 percent). The remaining 2 percent identified as adherents of other religions, including the Baháʼí Faith,[142] Buddhism,[143] and Islam.[144][139] The main Christian denominations are Anglicanism and other Protestantism, and Roman Catholicism.[145]

Education in the Falkland Islands, which follows England's system, is free and compulsory for residents aged between 5 and 16 years.[146] Primary education is available at Stanley, RAF Mount Pleasant (for children of service personnel) and a number of rural settlements. Secondary education is only available in Stanley, which offers boarding facilities and 12 subjects to General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) level. Students aged 16 or older may study at colleges in England for their GCE Advanced Level or vocational qualifications. The Falkland Islands government pays for older students to attend institutions of higher education, usually in the United Kingdom.[146]

Culture

Falklands culture is based on the cultural traditions of its British settlers but has also been influenced by Hispanic South America.[138] Falklanders still use some terms and place names from the former Gaucho inhabitants.[147] The Falklands' predominant and official language is English, with the foremost dialect being British English; nonetheless, some inhabitants also speak Spanish.[138] According to naturalist Will Wagstaff, "the Falkland Islands are a very social place, and stopping for a chat is a way of life".[147]

The islands have two weekly newspapers: Teaberry Express and The Penguin News,[148] and television and radio broadcasts generally feature programming from the United Kingdom.[138] Wagstaff describes local cuisine as "very British in character with much use made of the homegrown vegetables, local lamb, mutton, beef, and fish". Common between meals are "home made cakes and biscuits with tea or coffee".[149] Social activities are, according to Wagstaff, "typical of that of a small British town with a variety of clubs and organisations covering many aspects of community life".[150]

See also

- Index of Falkland Islands-related articles

- List of islands of the Falkland Islands

- Outline of the Falkland Islands

Notes

- ^ According to researcher Simon Taylor, the exact Gaelic etymology is unclear as the "falk" in the name could have stood for "hidden" (falach), "wash" (failc), or "heavy rain" (falc).[7]

- ^ Based on his analysis of Falkland Islands discovery claims, historian John Dunmore concludes that "[a] number of countries could therefore lay some claim to the archipelago under the heading of first discoverers: Spain, Holland, Britain, and even Italy and Portugal – although the last two claimants might be stretching things a little."[19]

- ^ In 1764, Bougainville claimed the islands in the name of Louis XV of France. In 1765, British captain John Byron claimed the islands in the name of George III of Great Britain.[21][22]

- ^ According to Argentine legal analyst Roberto Laver, the United Kingdom disregards Jewett's actions because the government he represented "was not recognized either by Britain or any other foreign power at the time" and "no act of occupation followed the ceremony of claiming possession".[29]

- ^ Before leaving for the Falklands Vernet stamped his grant at the British Consulate, repeating this when Buenos Aires extended his grant in 1828.[30] The cordial relationship between the consulate and Vernet led him to express "the wish that, in the event of the British returning to the islands, HMG would take his settlement under their protection".[31]

- ^ The log of the "Lexington" only reports the destruction of arms and a powder store, but Vernet made a claim for compensation from the US Government stating that the entire settlement was destroyed.[34]

- ^ As discussed by Roberto Laver, not only did Rosas not break relations with Britain because of the "essential" nature of "British economic support", but he offered the Falklands "as a bargaining chip ... in exchange for the cancellation of Argentina's million-pound debt with the British bank of Baring Brothers".[38] In 1850, Rosas' government ratified the Arana–Southern Treaty, which put "an end to the existing differences, and of restoring perfect relations of friendship" between the United Kingdom and Argentina.[39]

- ^ Argentina protested in 1841, 1849, 1884, 1888, 1908, 1927 and 1933, and has made annual protests to the United Nations since 1946.[41]

- ^ There were continual tensions with the colonial administration over Lafone's failure to establish any permanent settlers, and over the price of beef supplied to the settlement. Moreover, although his concession required Lafone to bring settlers from the United Kingdom, most of the settlers he brought were gauchos from Uruguay.[48]

- ^ The minefields were fenced off and marked; there remain unexploded ordnance and improvised explosive devices.[61] Detection and clearance of mines in the Falklands has proven difficult as some were air-delivered and not in marked fields; approximately 80% lie in sand or peat, where the position of mines can shift, making removal procedures difficult.[62]

- ^ In 1976, Lord Shackleton produced a report into the economic future of the islands; however, his recommendations were not implemented because Britain sought to avoid confronting Argentina over sovereignty.[64] Lord Shackleton was once again tasked, in 1982, to produce a report into the economic development of the islands. His new report criticised the large farming companies, and recommended transferring ownership of farms from absentee landlords to local landowners. Shackleton also suggested diversifying the economy into fishing, oil exploration, and tourism; moreover, he recommended the establishment of a road network, and conservation measures to preserve the islands' natural resources.[64]

- ^ Argentina considers that, in 1833, the UK established an "illegal occupation" of the Falklands after expelling Argentine authorities and settlers from the islands with a threat of "greater force" and, afterwards, barring Argentines from resettling the islands.[89][90][91] The Falkland Islands' government considers that only Argentina's military personnel was expelled in 1833, but its civilian settlers were "invited to stay" and did so except for 2 and their wives.[93] International affairs scholar Lowell Gustafson considers that "[t]he use of force by the British on the Falkland Islands in 1833 was less dramatic than later Argentine rhetoric has suggested".[94]

- ^ At the time of the 2012 census, 91 Falklands residents were overseas.[139]

References

- ^ a b "2016 Census Report". Policy and Economic Development Unit, Falkland Islands Government. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2018.

- ^ "State of the Falkland Islands Economy" (PDF). March 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b Avakov 2013, p. 54.

- ^ a b Avakov 2013, p. 47.

- ^ Jones 2009, p. 73.

- ^ See:

- Dotan 2010, p. 165,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Taylor & Márkus 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Room 2006, p. 129.

- ^ See:

- Paine 2000, p. 45,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Hince 2001, p. 121.

- ^ See:

- Hince 2001, p. 121,

- Room 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Balmaceda 2011, Chapter 36.

- ^ Foreign Office 1961, p. 80.

- ^ "Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications". United Nations Statistics Division. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ G. Hattersley-Smith (June 1983). "Fuegian Indians in the Falkland Islands". Polar Record. Cambridge University Press. 21 (135): 605–06. doi:10.1017/S003224740002204X.

- ^ a b Carafano 2005, p. 367.

- ^ White, Michael (2 February 2012). "Who first owned the Falkland Islands?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ^ Goebel 1971, pp. xiv–xv.

- ^ Dunmore 2005, p. 93.

- ^ See:

- Gustafson 1988, p. 5,

- Headland 1989, p. 66,

- Heawood 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Gustafson 1988, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Dunmore 2005, pp. 139–40.

- ^ See:

- Goebel 1971, pp. 226, 232, 269,

- Gustafson 1988, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Segal 1991, p. 240.

- ^ Gibran 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Gibran 1998, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c Gibran 1998, p. 27.

- ^ See:

- Gibran 1998, p. 27,

- Marley 2008, p. 714.

- ^ Laver 2001, p. 73.

- ^ Cawkell 2001, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Cawkell 2001, p. 50.

- ^ See:

- Gibran 1998, pp. 27–28,

- Sicker 2002, p. 32.

- ^ Pascoe & Pepper 2008, pp. 540–46.

- ^ a b Pascoe & Pepper 2008, pp. 541–44.

- ^ Peterson 1964, p. 106.

- ^ Graham-Yooll 2002, p. 50.

- ^ Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Laver 2001, pp. 122–23.

- ^ Hertslet 1851, p. 105.

- ^ Gustafson 1988, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Gustafson 1988, p. 34.

- ^ a b Graham-Yooll 2002, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Aldrich & Connell 1998, p. 201.

- ^ See:

- Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History,

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 9, 27.

- ^ a b c Reginald & Elliot 1983, p. 9.

- ^ a b Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History.

- ^ Strange 1987, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Strange 1987, p. 84.

- ^ a b See:

- Bernhardson 2011, Stanley and Vicinity: History,

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, p. 9.

- ^ Strange 1987, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Day 2013, p. 129–30.

- ^ Haddelsey & Carroll 2014, Prologue.

- ^ Zepeda 2005, p. 102.

- ^ a b Laver 2001, p. 125.

- ^ Thomas 1991, p. 24.

- ^ Thomas 1991, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Norton-Taylor, Richard; Evans, Rob (28 June 2005). "UK held secret talks to cede sovereignty: Minister met junta envoy in Switzerland, official war history reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Thomas 1991, pp. 28–31.

- ^ See:

- Reginald & Elliot 1983, pp. 5, 10–12, 67,

- Zepeda 2005, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Gibran 1998, pp. 130–35.

- ^ a b c "The Long Road to Clearing Falklands Landmines". BBC News. 14 March 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Ruan, Juan Carlos; Macheme, Jill E. (August 2001). "Landmines in the Sand: The Falkland Islands". The Journal of ERW and Mine Action. James Madison University. 5 (2). ISSN 1533-6905. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "Falklands community invited to 'Reclaim the Beach' to celebrate completion of demining – Penguin News". Penguin News. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cawkell 2001, p. 147.

- ^ "Falklands Drilling Will Resume in Second Quarter of 2015, Announced Premier Oil". MercoPress. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "The Falkland Islands, 30 Years After the War with Argentina". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ Grant Munro (8 December 2011). "Falklands' Land Mine Clearance Set to Enter a New Expanded Phase in Early 2012". MercoPress. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ See:

- Lansford 2012, p. 1528,

- Zepeda 2005, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Zepeda 2005, p. 103.

- ^ Cahill 2010, "Falkland Islands".

- ^ a b "New Year begins with a new Constitution for the Falklands". MercoPress. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ a b c "The Falkland Islands Constitution Order 2008" (PDF). The Queen in Council. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Buckman 2012, p. 394.

- ^ "Falklands' Swearing in Ceremony for Governor Phillips on 12 September". MercoPress. 2 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Falklands' new Chief Executive has 30 years experience in England's public sector". MercoPress. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ "Minister of State at the Foreign & Commonwealth Office". United Kingdom Government. 27 June 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Government".

- ^ "Falklands lawmakers: "The full time problem"". MercoPress. 28 October 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ EuropeAid (4 June 2014). "EU relations with Overseas Countries and Territories". European Commission. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b Sainato 2010, pp. 157–158.

- ^ "A New Approach to the British Overseas Territories" (PDF). London: Ministry of Justice. 2012. p. 4. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ "The Falkland Islands (Appeals to Privy Council) (Amendment) Order 2009", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, SI 2006/3205

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Transportation".

- ^ Martin Fletcher (6 March 2010). "Falklands Defence Force better equipped than ever, says commanding officer". The Times. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ International Boundaries Research Unit. "Argentina and UK claims to maritime jurisdiction in the South Atlantic and Southern Oceans". Durham University. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Lansford 2012, p. 1528.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (27 March 2009). "Falkland Islands sovereignty talks out of the question, says Gordon Brown". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Supporting the Falkland Islanders' right to self-determination". Policy. United Kingdom Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Ministry of Defence. 12 March 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores. "La Cuestión de las Islas Malvinas" (in Spanish). Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto (República Argentina). Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ a b Michael Reisman (January 1983). "The Struggle for The Falklands". Yale Law Journal. Faculty Scholarship Series. 93 (287): 306. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Decolonization Committee Says Argentina, United Kingdom Should Renew Efforts on Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Question". Press Release. United Nations. 18 June 2004. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Gustafson 1988, pp. 26–27.

- ^ "Relationship with Argentina". Self-Governance. Falkland Island Government. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Gustafson 1988, p. 26.

- ^ "No talks on Falklands, says Brown". BBC News. 28 March 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Falklands referendum: Islanders vote on British status". BBC News. 10 March 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Brindicci, Marcos; Bustamante, Juan (12 March 2013). "Falkland Islanders vote overwhelmingly to keep British rule". Reuters. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Timerman rejects meeting Falklands representatives; only interested in 'bilateral round' with Hague". MercoPress. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Laura Smith-Spark (11 March 2013). "Falkland Islands hold referendum on disputed status". CNN. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ See:

- Guo 2007, p. 112,

- Sainato 2010, p. 157.

- ^ Sainato 2010, p. 157.

- ^ a b c Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Geography".

- ^ Trewby 2002, p. 79.

- ^ a b Klügel 2009, p. 66.

- ^ a b Guo 2007, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hemmerle 2005, p. 318.

- ^ See:

- Blouet & Blouet 2009, p. 100,

- Central Intelligence Agency 2011, "Falkland Islands (Malvinas) – Geography"

- ^ Hince 2001, "Camp".

- ^ a b c Gibran 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Jónsdóttir 2007, pp. 84–86.

- ^ a b Helen Otley; Grant Munro; Andrea Clausen; Becky Ingham (May 2008). "Falkland Islands State of the Environment Report 2008" (PDF). Environmental Planning Department Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 131.

- ^ a b Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 132.

- ^ Clark & Dingwall 1985, p. 129.

- ^ Hince 2001, p. 370.

- ^ Chura, Lindsay R. (30 June 2015). "Pan-American Scientific Delegation Visit to the Falkland Islands". Science and Diplomacy.

The ocean’s fecundity also draws globally important seabird populations to the archipelago; the Falkland Islands host some of the world’s largest albatross colonies and five penguin species.

- ^ Jónsdóttir 2007, p. 85.

- ^ a b c "Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Bell 2007, p. 544.

- ^ Bell 2007, pp. 542–545.

- ^ a b Royle 2001, p. 171.

- ^ The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency. Cia.gov. Retrieved on 20 September 2017.

- ^ "Regions and territories: Falkland Islands". BBC News. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ See:

- Calvert 2004, p. 134,

- Royle 2001, p. 170.

- ^ "Agriculture". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ a b Royle 2001, p. 170.

- ^ Hemmerle 2005, p. 319.

- ^ Royle 2001, pp. 170–171.

- ^ "The Economy". Falkland Islands Government. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b "The Falkland Islands: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know in Data and Charts". The Guardian. 3 January 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ See:

- Bertram, Muir & Stonehouse 2007, p. 144,

- Prideaux 2008, p. 171.

- ^ See:

- Prideaux 2008, p. 171,

- Royle 2006, p. 183.

- ^ a b Laver 2001, p. 9.

- ^ a b "Falkland Islands Census Statistics, 2006" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Falkland Islands Government. "Falkland Islands Census 2016" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ See:

- Gibran 1998, p. 18,

- Laver 2001, p. 173.

- ^ Falklands still home to optimists as invasion anniversary nears, The Guardian, Andy Beckett, 19 March 2012

- ^ a b c d Minahan 2013, p. 139.

- ^ a b c d "Falkland Islands Census 2012: Headline results" (PDF). Falkland Islands Government. 10 September 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Falklands Referendum: Voters from many countries around the world voted Yes". MercoPress. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Royle 2006, p. 181.

- ^ "The Largest Baha'i (sic) Communities (mid-2000)". Adherents.com. September 2001. Archived from the original on 20 October 2001. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Falkland Islands Census Statistics 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010.

- ^ "The world in muslim populations, every country listed". The Guardian. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition [6 volumes] by J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ABC-CLIO, p. 1093.

- ^ a b "Education". Falkland Islands Government. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b Wagstaff 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wagstaff 2001, p. 65.

Bibliography

- Aldrich, Robert; Connell, John (1998). The Last Colonies. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41461-6.

- Avakov, Alexander (2013). Quality of Life, Balance of Powers, and Nuclear Weapons. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-963-6.

- Balmaceda, Daniel (2011). Historias Inesperadas de la Historia Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-3390-8.

- Bell, Brian (2007). "Introduced Species". In Beau Riffenburgh (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Antarctic. 1. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97024-2.

- Bernhardson, Wayne (2011). Patagonia: Including the Falkland Islands. Altona, Manitoba: Friesens. ISBN 978-1-59880-965-7.

- Bertram, Esther; Muir, Shona; Stonehouse, Bernard (2007). "Gateway Ports in the Development of Antarctic Tourism". Prospects for Polar Tourism. Oxon, England: CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-247-3.

- Blouet, Brian; Blouet, Olwyn (2009). Latin America and the Caribbean. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-38773-3.

- Buckman, Robert (2012). Latin America 2012. Ranson, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-61048-887-7.

- Cahill, Kevin (2010). Who Owns the World: The Surprising Truth About Every Piece of Land on the Planet. New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-55139-7.

- Calvert, Peter (2004). A Political and Economic Dictionary of Latin America. London: Europa Publications. ISBN 978-0-203-40378-5.

- Carafano, James Jay (2005). "Falkland/Malvinas Islands". In Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (eds.). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Cawkell, Mary (2001). The History of the Falkland Islands. Oswestry, England: Anthony Nelson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-904614-55-8.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2011). The CIA World Factbook 2012. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61608-332-8.

- Clark, Malcolm; Dingwall, Paul (1985). Conservation of Islands in the Southern Ocean. Cambridge, England: IUCN. ISBN 978-2-88032-503-9.

- Day, David (2013). Antarctica: A Biography (Reprint ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967055-0.

- Dotan, Yossi (2010). Watercraft on World Coins: America and Asia, 1800–2008. 2. Portland, Oregon: The Alpha Press. ISBN 978-1-898595-50-2.

- Dunmore, John (2005). Storms and Dreams. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-0-908988-57-0.

- Foreign Office (1961). Report on the Proceedings of the General Assembly of the United Nations. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- Gibran, Daniel (1998). The Falklands War: Britain Versus the Past in the South Atlantic. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-0406-3.

- Goebel, Julius (1971). The Struggle for the Falkland Islands: A Study in Legal and Diplomatic History. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0-8046-1390-3.

- Graham-Yooll, Andrew (2002). Imperial Skirmishes: War and Gunboat Diplomacy in Latin America. Oxford, England: Signal Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-902669-21-2.

- Guo, Rongxing (2007). Territorial Disputes and Resource Management. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60021-445-5.

- Gustafson, Lowell (1988). The Sovereignty Dispute Over the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504184-2.

- Haddelsey, Stephen; Carroll, Alan (2014). Operation Tabarin: Britain's Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica 1944–46. Stroud, England: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5511-9.

- Headland, Robert (1989). Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30903-5.

- Heawood, Edward (2011). F. H. H. Guillemard (ed.). A History of Geographical Discovery in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Reprint ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60049-2.

- Hemmerle, Oliver Benjamin (2005). "Falkland Islands". In R. W. McColl (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Geography. 1. New York: Golson Books, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3.

- Hertslet, Lewis (1851). A Complete Collection of the Treaties and Conventions, and Reciprocal Regulations, At Present Subsisting Between Great Britain and Foreign Powers, and of the Laws, Decrees, and Orders in Council, Concerning the Same. 8. London: Harrison and Son.

- Hince, Bernadette (2001). The Antarctic Dictionary. Collingwood, Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9577471-1-1.

- Jones, Roger (2009). What's Who? A Dictionary of Things Named After People and the People They are Named After. Leicester, England: Matador. ISBN 978-1-84876-047-9.

- Jónsdóttir, Ingibjörg (2007). "Botany during the Swedish Antarctic Expedition 1901–1903". In Jorge Rabassa; Maria Laura Borla (eds.). Antarctic Peninsula and Tierra del Fuego. Leiden, Netherlands: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-41379-4.

- Klügel, Andreas (2009). "Atlantic Region". In Rosemary Gillespie; David Clague (eds.). Encyclopedia of Islands. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25649-1.

- Lansford, Tom (2012). Thomas Muller; Judith Isacoff; Tom Lansford (eds.). Political Handbook of the World 2012. Los Angeles, California: CQ Press. ISBN 978-1-60871-995-2.

- Laver, Roberto (2001). The Falklands/Malvinas Case. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-1534-8.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8.

- Minahan, James (2013). Ethnic Groups of the Americas. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-163-5.

- Paine, Lincoln (2000). Ships of Discovery and Exploration. New York: Mariner Books. ISBN 978-0-395-98415-4.

- Pascoe, Graham; Pepper, Peter (2008). "Luis Vernet". In David Tatham (ed.). The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (Including South Georgia): From Discovery Up to 1981. Ledbury, England: David Tatham. ISBN 978-0-9558985-0-1.

- Peterson, Harold (1964). Argentina and the United States 1810–1960. New York: University Publishers Inc. ISBN 978-0-87395-010-7.

- Prideaux, Bruce (2008). "Falkland Islands". In Michael Lück (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Tourism and Recreation in Marine Environments. Oxon, England: CAB International. ISBN 978-1-84593-350-0.

- Reginald, Robert; Elliot, Jeffrey (1983). Tempest in a Teapot: The Falkland Islands War. Wheeling, Illinois: Whitehall Co. ISBN 978-0-89370-267-0.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World (2nd ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- Royle, Stephen (2001). A Geography of Islands: Small Island Insularity. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-16036-7.

- Royle, Stephen (2006). "The Falkland Islands". In Godfrey Baldacchino (ed.). Extreme Tourism: Lessons from the World's Cold Water Islands. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-044656-1.

- Sainato, Vincenzo (2010). "Falkland Islands". In Graeme Newman; Janet Stamatel; Hang-en Sung (eds.). Crime and Punishment around the World. 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35133-4.

- Segal, Gerald (1991). The World Affairs Companion. New York: Simon & Schuster/Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-671-74157-0.

- Sicker, Martin (2002). The Geopolitics of Security in the Americas. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-97255-4.

- Strange, Ian (1987). The Falkland Islands and Their Natural History. Newton Abbot, England: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8833-4.

- Taylor, Simon; Márkus, Gilbert (2005). The Place-Names of Fife: Central Fife between the Rivers Leven and Eden. Donington, England: Shaun Tyas. ISBN 978-1900289-93-1.

- Thomas, David (1991). "The View from Whitehall". In Wayne Smith (ed.). Toward Resolution? The Falklands/Malvinas Dispute. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55587-265-6.

- Trewby, Mary (2002). Antarctica: An Encyclopedia from Abbott Ice Shelf to Zooplankton. Richmond Hill, Ontario: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-590-9.

- Wagstaff, William (2001). Falkland Islands: The Bradt Travel Guide. Buckinghamshire, England: Bradt Travel Guides, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84162-037-4.

- Zepeda, Alexis (2005). "Argentina". In Will Kaufman; Heidi Slettedahl Macpherson (eds.). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. Santa Barbara, California: ABC–CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

Further reading

- Caviedes, César (1994). "Conflict Over The Falkland Islands: A Never-Ending Story?". Latin American Research Review. 29 (2): 172–187. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- Darwin, Charles (1846). "On the Geology of the Falkland Islands" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 2 (1–2): 267–274. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1846.002.01-02.46. S2CID 129936121. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés, eds. (2000). Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas. Buenos Aires, Argentina: GEL/Nuevohacer. ISBN 978-950-694-546-6. Work developed and published under the auspices of the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI).

- Freedman, Lawrence (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. Oxon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5207-8.

- Michael Frenchman (28 November 1980). "Britain puts forward four options on Falklands (Nick Ridley visit & leaseback)". The Times. p. 7. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- Greig, D. W. (1983). "Sovereignty and the Falkland Islands Crisis" (PDF). Australian Year Book of International Law. 8: 20–70. doi:10.1163/26660229-008-01-900000006. ISSN 0084-7658.

- Ivanov, L. L.; et al. (2003). . Sofia, Bulgaria: Manfred Wörner Foundation. ISBN 978-954-91503-1-5. Printed in Bulgaria by Double T Publishers.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands

Wikimedia Atlas of Falkland Islands- Falkland Islands Government (official site)

- Falkland Islands Development Corporation (official site)

- Falkland Islands News Network (official site)

- Falkland Islands Profile (BBC)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). 1911.

| Portals Access related topics |

|

| Find out more on Wikipedia's Sister projects |

|