Депортация армянской интеллигенции 24 апреля 1915 г.

| Депортация армянской интеллигенции | |

|---|---|

| Часть геноцида армян | |

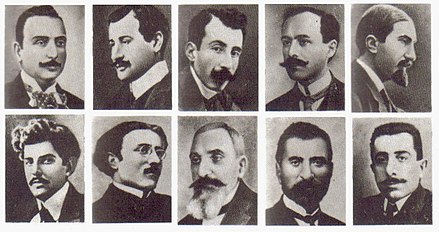

Некоторые из армянских интеллектуалов, которые были задержаны, депортированы и убиты в 1915 году: 1-й ряд : Крикор Зохраб , Даниэль Варужан , Рупен Зартарян , Ардашес Арутюнян , Сиаманто 2-й ряд : Рубен Севак , Дикран Чокюрян , Диран Келекян , Тлгадинци и Эрухан | |

| Место расположения | Османская империя |

| Дата | 24 апреля 1915 г. (дата начала) |

| Цель | Знаменитости армянской общины Константинополя |

| Тип атаки | Депортация и возможное убийство |

| Преступники | Комитет Союза и Прогресса ( младотурки ) |

Депортация армянской интеллигенции традиционно считается началом геноцида армян . [1] Лидеры армянской общины в столице Османской империи Константинополе (ныне Стамбул ), а затем и в других местах были арестованы и переведены в два изолятора недалеко от Ангоры (ныне Анкара ). Приказ об этом был отдан министром внутренних дел Талаат-пашой 24 апреля 1915 года. Той ночью была арестована первая волна от 235 до 270 армянских интеллектуалов Константинополя . С принятием Закона Техчир 29 мая 1915 года эти задержанные были позже переселены в пределах Османской империи ; большинство из них в конечном итоге были убиты. Выжили более 80 человек, в том числе Вртанес Папазян , Арам Андонян и Комитас .

The event has been described by historians as a decapitation strike,[2][3] which was intended to deprive the Armenian population of leadership and a chance for resistance.[4] To commemorate the victims of the Armenian genocide, 24 April is observed as Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. First observed in 1919 on the four-year anniversary of the events in Constantinople, the date is generally considered the date on which the genocide began. The Armenian genocide has since been commemorated annually on the same day, which has become a national holiday in Armenia and the Republic of Artsakh and is observed by the Armenian diaspora around the world.

Deportation

Detention

Министр внутренних дел Османской империи Талаат-паша издал приказ о задержании 24 апреля 1915 года. Операция началась в 20:00 [5] . В Константинополе акцией руководил Бедри-бей, начальник полиции Константинополя. [6] В ночь с 24 на 25 апреля 1915 года в ходе первой волны 235–270 армянских лидеров Константинополя, священнослужителей, врачей, редакторов, журналистов, юристов, учителей, политиков и других лиц были арестованы по указанию Министерства внутренних дел. интерьер. [7] [8] Расхождения в цифрах можно объяснить неуверенностью полиции, заключавшей в тюрьму людей с похожими именами.

Были дальнейшие депортации из столицы. Первой задачей было установить личность заключенных. Их продержали в течение одного дня в полицейском участке (на османском языке: Emniyeti Umumiye ) и в центральной тюрьме. Вторая волна довела цифру до 500-600. [7] [9] [10] [11]

К концу августа 1915 года около 150 армян с российским гражданством были депортированы из Константинополя в центры содержания под стражей. [12] Некоторые из задержанных, в том числе писатель Александр Паносян (1859–1919), были освобождены в те же выходные до того, как их отправили в Анатолию. [13] Всего, по оценкам, 2345 армянских знатных деятелей были задержаны и в конечном итоге депортированы [14] [15] , большинство из которых не были националистами и не имели какой-либо политической принадлежности. [14]

Центры содержания

After the passage of Tehcir Law on 29 May 1915, Armenians left at the two holding centers were deported to Ottoman Syria. Most of the arrested were transferred from Central Prison over Saray Burnu by steamer No. 67 of the Şirket company to the Haydarpaşa train station. After waiting for ten hours, they were sent by special train in the direction of Angora (Ankara) the next day. The entire convoy consisted of 220 Armenians.[16] An Armenian train conductor got a list of names of the deportees. It was handed over to the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, Zaven Der Yeghiayan, который сразу же тщетно пытался спасти как можно больше депортированных. Единственным иностранным послом, который помог ему в его усилиях, был посол США Генри Моргентау . [17] После 20-часовой поездки на поезде депортированные вышли в Синканкёй (недалеко от Ангоры) в полдень во вторник. На станции Ибрагим, директор Центральной тюрьмы Константинополя, проводил сортировку. Депортированные были разделены на две группы.

Одну группу отправили в Чанкыры (и Чорум между Чанкыры и Амасья ), а другую - в Аяш . Те, кто был разлучен для Аяша, были доставлены на телегах на пару часов дальше в Аяш. Почти все они были убиты несколько месяцев спустя в ущельях близ Ангоры. [18] Только 10 (или 13) [6] депортированных из этой группы получили разрешение вернуться в Константинополь из Аяша. [n 1] Группа из 20 опоздавших, арестованных 24 апреля, прибыла в Чанкыры примерно 7 или 8 мая 1915 года. [19] Примерно 150 политических заключенных были задержаны в Аяше, а еще 150 интеллектуальных заключенных были задержаны в Чанкыры. [20]

Военно-полевой суд

Некоторые известные личности, такие как доктор Назарет Дагаварян и Саркис Минасян , были вывезены 5 мая из тюрьмы Айаш и доставлены под военным конвоем в Диярбакыр вместе с Арутюном Джангуляном , Карекином Хаджагом и Рупеном Зартаряном , чтобы предстать перед военным трибуналом. По всей видимости, они были убиты спонсируемыми государством военизированными группами во главе с Черкесом Ахметом и лейтенантами Халилом и Назимом в местности под названием Караджаорен незадолго до прибытия в Диярбакыр. [13] Марзбед, еще один депортированный, был отправлен в Кайсери, чтобы предстать перед военным трибуналом 18 мая 1915 года. [21]

Боевики, виновные в убийствах, были преданы суду и казнены в Дамаске Джемалом-пашой в сентябре 1915 года; Позже этот инцидент стал предметом расследования 1916 года, проведенного парламентом Османской империи во главе с Артином Бошгезенианом , депутатом от Алеппо. После освобождения Марзбеда от двора он работал под фальшивым османским именем на немцев в Интилли (железнодорожный туннель Аманус). Он сбежал в Нусайбин, где упал с лошади и умер незадолго до перемирия. [21]

Выпуск

Несколько заключенных были освобождены с помощью различных влиятельных людей, вмешавшихся в их дела. [22] Пятеро депортированных из Чанкыры были освобождены после вмешательства посла США Генри Моргентау . [6] В общей сложности 12 депортированным было разрешено вернуться в Константинополь из Чанкыры. [n 2] Это были Комитас , Пиузант Кечян, доктор Ваграм Торкомян, доктор Парсег Динанян, Хайг Ходжасарян, Ншан Калфаян, Ервант Толаян, Арам Календериан, Нойиг Дер-Степанян, Вртанес Папазян , Карник Инджиджян и Бейлериан младший. Четверым депортированным было разрешено вернуться из Коньи. [n 3]Это были Апиг Миубахеджян, Атамян, Хербекян, Носригян. [12]

Остальные депортированные находились под защитой губернатора Ангорского вилайета . Мажар-бей нарушил приказ о депортации министра внутренних дел Талат-паши [23] и к концу июля 1915 года был заменен членом центрального комитета Атифом беем [24] .

Выжившие

После Мудросского перемирия (30 октября 1918 г.) несколько уцелевших армянских интеллектуалов вернулись в Константинополь, который находился под оккупацией союзников . Они начали короткую, но интенсивную литературную деятельность, которая завершилась победой Турции в 1923 году. Среди тех, кто написал мемуары и книги о своих счетах во время депортации, были Григорис Балакян , Арам Андонян , Ервант Одиан , Теотиг и Микаел Шамтанчян. [25] У других выживших, таких как Комитас , развились серьезные случаи посттравматического стрессового расстройства . Комитас провел 20 лет лечения в психиатрических больницах до своей смерти в 1935 году.[26]

День памяти

Официальная дата поминовения геноцида армян - 24 апреля, день, когда началась депортация армянской интеллигенции. Первое поминовение, организованное группой переживших Геноцид армян, было проведено в Стамбуле в 1919 году в местной армянской церкви Святой Троицы. В поминовении приняли участие многие видные деятели армянской общины. После первого поминовения в 1919 году этот день стал ежегодным днем памяти жертв геноцида армян. [27]

Известные депортированные

Below is a list of prominent Armenian intellectuals, community leaders and other public figures that were deported from Constantinople on 24 April 1915, the first wave of the deportations. The list of names are those that have been provided in the Ottoman Archives and various Armenian sources:

| Name[n 4] | Birth date and place[n 5] | Fate | Political affiliation | Occupation | Deported to | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarkis Abo Սարգիս Ապօ | Killed | Dashnak | Teacher | Ayaş | Armenian from Caucasus, killed in Angora (Ankara).[21] | |

| Levon Aghababian Լեւոն Աղապապեան | 1887 from Bitlis | Died | Математик, директор средних школ в Кютахья и Акшехир (1908–14), руководил своей собственной школой в Кютахье в течение трех лет [28] | Чанкыры | Умер в 1915 году. [28] | |

| Грант Агаджанян Հրանդ Աղաճանեան | Убит | Чанкыры | Привезен к виселице на площади Беязит (Константинополь) 18 января 1916 года. [12] | |||

| Мигран Агаджанян Միհրան Աղաճանեան | Убит | Банкир [21] | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь, где его бросили на виселицу. [21] | ||

| Мигран Агасян Միհրան Աղասեան | 1854 г. в Адрианополе ( Эдирне ) | Убит | Поэт и музыкант | Der Zor | Депортирован в Дер Зор, где был убит в 1916 году. [29] | |

| Хачатур Малумян Խաչատուր Մալումեան | 1865 г. в Зангезуре | Убит | Дашнакский | Дашнакский боевик, редактор газеты, сыграл роль в организации собрания сил, противостоящих османскому султану, что привело к провозглашению Османской конституции в 1908 году. | Айаш | Removed from the Ayaş prison on 5 May and taken under military escort to Diyarbakır along with Daghavarian, Jangülian, Khajag, Minassian and Zartarian to appear before a court martial there and they were, seemingly, murdered by state-sponsored paramilitary groups led by Cherkes Ahmet, and lieutenants Halil and Nazım, at a locality called Karacaören shortly before arriving at Diyarbakır.[13] The murderers were tried and executed in Damascus by Cemal Pasha in September 1915, and the assassinations became the subject of a 1916 investigation by the Ottoman Parliament led by Artin Boshgezenian, the deputy for Aleppo. |

| Дикран Аджемян Տիգրան Աճեմեան | Выжил | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь [21] из группы из десяти депортированных из Аяша. [12] | |||

| Дикран Аллахверди Տիգրան Ալլահվերտի | Выжил | Член различных патриархальных советов | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь. [21] | ||

| Ваан Алтунян Վահան Ալթունեան | Выжил | Стоматолог [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 года. [30] Он покинул Чанкыры 6 августа 1915 года, был заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре, был перемещен в Тарсон, прибыл в Константинополь 22 сентября 1915 года. [28] | ||

| Ваграм Алтунян Վահրամ Ալթունեան | Умер [28] | Торговец [28] | Чанкыры | |||

| Арам Андонян Արամ Անտոնեան | 1875 г. в Константинополе | Выжил | Гунчак [31] Հնչակեան Վերակազմ [32] | Писатель и журналист; депутат Национального Собрания Армении [33] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, которые покинули Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, сломали ногу, попали в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, а затем сбежали после госпитализации в Ангорскую больницу. [34] Он присоединился к другому каравану депортированных и вернулся в Константинополь только после того, как Тарс, Мардин, Дер Зор, Халеб, [28] он оставался в концентрационных лагерях вокруг города Мескене в пустыне, [31] опубликовал свои опыты в своих литературных источниках. работы В те мрачные дни он редактировал сборник телеграмм, подлинность которых оспаривается, содержащие приказы Талат-паши об уничтожении; он стал директором библиотеки AGBU Nubar в Париже с 1928 по 1951 год. [35] |

| В. Арабский Վ. Արապեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Саркис Армданци Սարգիս Արմտանցի | Убит | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |||

| К. Армуни Գ. Արմունի | Юрист [8] | |||||

| Асадур Арсеньян Ասատուր Արսենեան | Убит | Фармацевт [28] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, которые покинули Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключены в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убиты по пути в Йозгат [34] или умерли недалеко от Дер Зора. [28] | ||

| Арсланян Արսլանեան | Торговец (?) [28] | Чанкыры | ||||

| Арцруни Արծրունի | Убито [12] | Патриот или педагог [8] | Чанкыры | |||

| Баруйр Арзуманян Պարոյր Արզումանեան | Убит | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя оставшимися в живых, которые покинули Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключены в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убиты по пути в Йозгат. [34] | |||

| Ваграм Асадурян Վահրամ Ասատուրեան | из Гедикпаша | Выжил [18] | Фармацевт | Чанкыры | Депортирован в Мескене, где, наконец, отслужил в армии фельдшером и помогал депортированным армянам. [28] | |

| Х. Асадурян Յ. Ասատուրեան | Выжил | Владелец типографии [12] | Айаш | Получил разрешение вернуться. [12] | ||

| Арутюн Асдуриан Յարութիւն Աստուրեան | Убит | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |||

| Грант Асдвадзадрян Հրանդ Աստուածատրեան | Выжил | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь. [21] | |||

| Д. Ашхаруни Տ. Աշխարունի | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Атамян Ադամեան | из Эрзурума | Выжил | Торговец [12] | Конья | Получил разрешение вернуться. [12] | |

| Вартерес Атанасян Վարդերես Աթանասեան | 1874 г. | Умер | Гунчак | «Староста» (мухтар) Ферикёй, купец [28] | Чанкыры | Умер в 1916 (?) [28] |

| Егисе Каханай Айвазян Եղիսէ Քհնյ. Այվազեան | 13 октября 1870 г. в Болу | Священнослужитель | Заключен в тюрьму в Константинополе на два месяца | Депортирован в Конью, Бей Шехир, Конью, Улукшлу, Эрейли (где встретил множество священнослужителей из Бардизага), Бозанти, Кардаклик, Тарсус. Он покинул Тарс 15 октября 1915 года в направлении Османие, Ислахие, Тахтакепрю к окраинам Алеппо. [8] | ||

| Азарик Ազարիք | Умер | Фармацевт | Чанкыры | Умер в Дер Зоре. [18] | ||

| Григорис Балакян Գրիգորիս Պալաքեան | 1879 г. в Токате | Выжил | Священнослужитель | Чанкыры | Сбежал. После войны жил в Манчестере и Марселе - опубликовал мемуары [36] о изгнании. [13] Умер в Марселе в 1934 году. | |

| Балассан Պալասան | Мусульманин из Персии | Убит | Усыновлена дашнаками в детстве | Швейцар и кофейник для редакции Azadamard | Айаш | Убит, несмотря на вмешательство персидского посольства. |

| Хачиг Бардизбанян Խաչիկ Պարտիզպանեան | Убит | Общественный деятель | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | ||

| Левон Бардизбанян Լեւոն Պարտիզպանեան | 1887 г. в Харперте | Дашнак [28] | Врач и директор Азадамара | |||

| Вагинаг Бардизбанян Վաղինակ Պարտիզպանեան | Выжил | Должностное лицо судоходной компании Хайрие [18] [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | ||

| Заре Бардизбанян Զարեհ Պարտիզպանեան | Выжил | Дантист | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь специальной телеграммой от Талат-паши 7 мая 1915 года. [37] [38] Восемь заключенных этой группы были уведомлены в воскресенье, 9 мая 1915 года, об их освобождении [38] и покинули Чанкыры 11 мая 1915 года. . [30] | ||

| Манук Басмаджян Մանուկ Պասմաճեան | Выжил [28] | Архитектор и интеллектуал [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | ||

| Мкртич Басмаджян [n 6] Մկրտիչ Պասմաճեան | Выжил | Торговец оружием [18] | Чанкыры | Отправлен в Измит для дальнейших допросов вместе с другими депортированными. Бежал в Конью. Был снова депортирован, сумел бежать на полпути в Дер Зор и вернулся в Константинополь. [28] | ||

| Д. Баздикян Տ. Պազտիկեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Бедиг Պետիկ | Писатель, публицист [8] | |||||

| Мовсес Бедросян Մովսէս Պետրոսեան | Дашнакский | Учитель | Чанкыры | Освободился, поскольку был болгарским гражданином и вернулся в Софию. [18] | ||

| Г. Бейликджян Կ . Պէյլիքճեան | Торговец [8] | |||||

| Хачиг Берберян Խաչիկ Պէրպէրեան | Выжил | Учитель [21] | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь. [21] | ||

| Э. Беязян Ե. Պէյազեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Бейлериан Պէյլերեան | Сын Акопа Бейлериана | Чанкыры | ||||

| Акоп Бейлериан Յակոբ Պէյլերեան | 1843 г. из Кайсери (?) [39] | Выжил [28] | Отец бейлерианского сына [28] | Торговец [28] | Чанкыры | Получив разрешение вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 года, [30] умер в 1921 году (?) [39] |

| Артин Богосян Արթին Պօղոսեան | Выжил | Чанкыры | «Помилован при условии невозвращения в Константинополь», согласно телеграмме из Министерства внутренних дел от 25 августа 1915 года о ссыльных, ошибочно не упомянутых в телеграмме от 3 августа. [40] | |||

| Хачиг Богосян Խաչիկ Պօղոսեան | Выжил | Врач, психолог, депутат Национального Собрания Армении [28] | Айаш | Арестован 24 апреля 1915 г., сослан 3 мая 1915 г. Он прибыл в Константинополь после дальнейшей депортации из Аяша в Ангору и Алеппо после перемирия. [28] После войны жил в Алеппо. Основал больницу. Опубликовал свои воспоминания о ссылке [13] - д. 1955 год в Алеппо . | ||

| Ампарцум Бояджян (Мурад) Համբարձում Պօյաճեան (Մուրատ) | 1867 г. в Хаджине ( сегодня Саймбейли ) | Убит | Гунчак | Доктор, с долгой и хорошо известной историей политической деятельности и агитации, один из первых организаторов Гунчак в 1888 году и один из его лидеров, главный организатор битвы в Кумкапы 1890 года , лидер восстания Сасуна 1894–1895 годов, после 1908 г. Делегат Национального собрания Армении от Кумкапы и депутат османского парламента от Аданы . Мурад был его псевдонимом . [13] | Чанкыры | Его привели в Кайсери , чтобы предстать перед военным трибуналом, а затем казнили там в 1915 году [21] . |

| Пюзант Бозаджян Բիւզանդ Պօզաճեան | Выжил | Депутат Национального Собрания Армении [21] | Айаш | Вернулся в Константинополь. [21] | ||

| Gh. Чплакян Ղ. Չպլաքեան | Выжил | Конья | Депортирован в Конью, Тарсус, Кушулар, Белемедик. После перемирия вернулся в Константинополь. [12] | |||

| Ервант Чавушян Երունդ Չաւուշեան | 1867 г. Константинополь [28] | Умер | Гунчак | Армянский ученый, педагог, главный редактор газеты "Цайн Айреняц". | Чанкыры | Депортирован в Хаму , Дер Зор , где скончался от болезни. [29] Он умер в то же время в одной палатке в деревне недалеко от Мескене, что и Хусиг А. Каханай Катчуни. [18] |

| Чебджи Ջպճը | Армяно-католический [28] | Архитектор | Чанкыры | |||

| Дикран Чокюриан Տիգրան Չէօկիւրեան | 1884 Гюмушкана | Убит | Писатель, публицист, [8] педагог и главный редактор журнала « Востан » . [21] | Айаш | Убит в Ангоре; брат Чокюриана ниже [21] | |

| Чокюриан Չէօկիւրեան | Писатель, публицист [8] | Брат Дикрана Чокюряна | ||||

| Каспар Чераз Գասպար Չերազ | 1850 г. в Хаскёй | Выжил | Юрист, общественный деятель, брат Минаса Чераза | Чанкыры | Уехал из Чанкыры зимой через семь месяцев и пережил следующие три года в качестве беженца в Ушаке вместе со своими товарищами Овханом Вартапедом Гарабедяном, Микаелом Шамтанчяном, Варданом Каханай Карагезяном из Ферикёя. После перемирия вернулся в Константинополь. [8] Он был депортирован вместо своего брата Минаса Чераса, который эмигрировал во Францию, Каспар Черас умер в 1928 году в Константинополе. [28] | |

| К. Чухаджян Գ. Չուհաճեան | Торговец [8] | |||||

| Аарон Дадуриан Ահարոն Տատուրեան | 1886 год в Оваджике (недалеко от Измита) | Выжил | Поэт [12] | Эрегли | Returned to Constantinople after the armistice.[12] After a brief sojourn in Constantinople and Bulgaria, he pursued his studies in Prague (1923–28) and settled in France in the late 1920s. He died in 1965.[35] | |

| Nazaret Daghavarian Նազարէթ Տաղաւարեան | 1862 Sebastia | Killed | Physician, director of Surp Prgitch Hospital, deputy in the Ottoman parliament, deputy for Sivas in the Armenian National Assembly, founding member of Armenian General Benevolent Union. | Ayaş | Вывезены из тюрьмы Аяш 5 мая и доставлены под военным конвоем в Диярбакыр вместе с Агнуни, Джангюляном, Хаджагом, Минасяном и Зартарианом, чтобы предстать перед военным трибуналом, и они, по-видимому, были убиты спонсируемыми государством военизированными группами во главе с Черкесом Ахметом . , и лейтенанты Халил и Назим в местности под названием Караджаорен незадолго до прибытия в Диярбакыр [ 13] были убиты по дороге в Урфу. [21] Убийц судил и казнил в Дамаске Джемаль-паша .В сентябре 1915 года эти убийства стали предметом расследования 1916 года, проведенного Османским парламентом во главе с Артином Бошгезенианом , депутатом от Алеппо. | |

| Даниелян Դանիէլեան | Выжил [18] | Гунчак | Портной [18] | Чанкыры | ||

| Богос Даниелян Պօղոս Դանիէլեան | Умер | Дашнакский | Юрист [8] | Чанкыры | Умер в Дер Зоре. [18] | |

| Гарабед Деовлетян Կարապետ Տէօվլեթեան | Выжил | Офицер монетного двора [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | ||

| Нерсес Дер-Каприелян (Shahnour) Ներսես Տէր-Գաբրիէլեան (Շահնուր) | из Кайсери | Убит | Чанкыры | Belonged to the second convoy with only one[6] or two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat.[34] | ||

| Noyig Der-Stepanian[n 7] Նոյիկ Տէր-Ստեփանեան | from Erzincan[28] | Survived | Commission agent, merchant and banker[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] About 40 members of his family died.[28] | |

| Parsegh Dinanian Բարսեղ Տինանեան | Survived | Physician | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] One of the organizers of the commemoration ceremony of 24 April 1919.[28] | ||

| K. Diratsvian Գ. Տիրացուեան | Писатель, публицист [8] | |||||

| Хор. Дхруни Խոր. Տխրունի | Писатель, публицист [8] | |||||

| Крикор Джелал Գրիգոր Ճելալ | Выжил | Гунчак [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | ||

| Мисак Джевахирджян Միսաք Ճէվահիրճեան | 1858 г. из Кайсери | Выжил | Врач (гинеколог в суде), член коллегии [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь 11 мая 1915 года. [30] Восемь заключенных этой группы были уведомлены в воскресенье, 9 мая 1915 года, об их освобождении [38] и покинули Чанкыры 11 мая 1915 года. [30] Освобождены с помощью своего друга Песина Омера Паша, умер в 1924 году. [28] | |

| Армен Дориан (Грачия Суренян) Արմէն Տօրեան (Հրաչեայ Սուրէնեան) | 1892 г. Синоп | Убит | Французско-армянский поэт, редактор еженедельника "Арен" (Париж), основоположник пантеистической школы. [41] | Чанкыры | В 1914 году окончил Сорбоннский университет и вернулся в Константинополь . [41] Депортирован в Чанкыры, убит в анатолийской пустыне; [29] был заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре после Чанкыры и убит, согласно Ншану Калфаяну, [28] убит недалеко от Ангоры. [18] | |

| Крис Фенерджян (Сильвио Риччи) | Выжил | Айаш | Освободился как болгарский гражданин и вернулся в Болгарию. [12] [21] | |||

| Парунак Ферухан Բարունակ Ֆէրուխան | 1884 г. в Константинополе [28] | Убит | Сотрудник администрации Бакыркёй (Макрикёй) и скрипач [28] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, который покинул Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убит по пути в Йозгат. [34] | |

| Оган Вартапед Гарабедян Յովհան Վրդ. Կարապետեան | 22 июня 1888 г. в Брусе | Выжил | Священник, магистр Колумбийского университета , секретарь патриарха Завена [8] | Чанкыры | Учился в США, вернулся в 1914 г. и был рукоположен в священники 16 июня 1914 г. в Эчмиадзине. Он уехал из Чанкыры зимой через семь месяцев и пережил следующие три года в качестве беженца в Ушаке вместе со своими товарищами Каспаром Черазом, Микаелом Шамтанчяном, Варданом Каханай Карагезяном из Ферикёй. После перемирия он вернулся в Константинополь и стал священником в Гедикпаше и Балате, членом религиозного совета. С 20 июля 1919 г. по 5 августа 1920 г. он был избран примасом Измира. Позже он получил более высокую степень целомудрия священника (Ծ. Վրդ.). 8 января 1921 года он уехал в Америку и стал священником церкви Святого Лусаворича в Нью-Йорке. [8] Он выжил и оставил духовенство. [18] | |

| Мкртич Гарабедян Մկրտիչ Կարապետեան | Выжил | Армяно-католический [12] | Айаш | Получил разрешение вернуться в столицу, поскольку был ошибочно заключен в тюрьму вместо учителя с таким же именем. [12] | ||

| Газарос Ղազարոս | Дашнакский | Чанкыры | Депортирован вместо Марзбеда (Газар Казарян). [28] | |||

| Ghonchegülian Ղոնչէկիւլեան | Умер | Торговец из Акна [28] | Чанкыры | Погиб под Мескене. [18] | ||

| Крикор Торосян (Гиго) Գրիգոր Թորոսեան (Կիկօ) | 1884 г. в Акне | Убит | Редактор сатирической газеты Gigo [21] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |

| Гюлюстанян Կիւլուստանեան | Убито [13] / Выживших [18] | Дантист | Чанкыры | "Permitted to reside freely in Çankırı" according to a telegramme from the Ministry of the Interior on 25 August 1915 on the subject of exiles erroneously unlisted in a former 3 August telegramme.[40] Killed in a village called Tüney in 1915, together with Ruben Sevak, Daniel Varoujan and Mağazacıyan[13] in a group of five. | ||

| Melkon Gülustanian Մելքոն Կիւլուստանեան | Survived | Ayaş | Relative of his namesake in Çankırı;[28] set free and returned to Constantinople.[21] | |||

| Haig Goshgarian Հայկ Կօշկարեան | Survived | Editor of Odian and Gigo | Der Zor | Survived deportation to Der Zor and returned to Constantinople after the armistice.[12] | ||

| Reverend Grigorian Սուրբ Հայր Գրիգորեան | Pastor and editor of Avetaper[18] | Çankırı | ||||

| Melkon Gülesserian Մելքոն Կիւլեսերեան | Survived | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] | |||

| Mihrdat Haigazn Միհրդատ Հայկազն | Killed | Dashnak | Patriot or educator,[8] member of Armenian National Assembly, umbrella merchant.[21] | Ayaş | Banished a couple of times and then killed in Angora.[21] | |

| K. Hajian Գ. Հաճեան | Survived | Pharmacist | Çankırı | Returned from Çankırı after the armistice.[28] | ||

| Hampartsum Hampartsumian Համբարձում Համբարձումեան | 1890 in Constantinople | Killed | Writer, publicist[8] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Hovhannes Hanisian Յովհաննէս Հանիսեան | Survived | Çankırı | "Pardoned on condition on not returning to Constantinople" according to a telegramme from the Ministry of the Interior on 25 August 1915 on the subject of exiles erroneously unlisted in a former 3 August telegramme.[40] | |||

| Ardashes Harutiunian Արտաշէս Յարութիւնեան | 1873 Malkara (near Rodosto) | Killed | Writer, publicist[8] | Оставался в Ускюдаре 24 апреля 1915 года. Арестован 28 июля 1915 года и жестоко избит в Мюдюриет. Когда его отец приехал навестить его, он тоже попал в тюрьму. Отец и сын были депортированы вместе с 26 армянами в Никомедию (современный Измит) и заключены в армянскую церковь, превращенную в тюрьму. В конце концов зарезан вместе со своим отцом недалеко от Дербента 16 августа 1915 года [12] . | ||

| Авраам Айрикян Աբրահամ Հայրիկեան | Убит | Тюрколог, директор колледжа Арди , депутат Национального Собрания Армении [21] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | ||

| К. Хиусиан Գ. Հիւսեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Хайг Ходжасарян Հայկ Խօճասարեան | Выжил | Teacher, educator, headmaster of Bezciyan school (1901–1924),[39] politician in Ramgavar | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople mid-June 1915, deputy of the Armenian National Assembly in 1919[28] became later chancellor of the Diocese of the Armenian Church of America.[13] | ||

| Mkrtich Hovhannessian Մկրտիչ Յովհաննէսեան | Killed | Dashnak | Teacher | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Mkrtich Hovhannessian Մկրտիչ Յովհաննէսեան | Survived | Ayaş | Deported in lieu of Dashnak member Mkritch Hovhannessian, returned to Constantinople.[21] | |||

| Melkon Giurdjian (Hrant) Մելքոն Կիւրճեան (Հրանդ) | 1859 in Palu | Killed | Dashnak | Writer, publicist,[8] armenologist, member of Armenian National Assembly[21] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] |

| Krikor Hürmüz Գրիգոր Հիւրմիւզ | Killed[12] | Writer, publicist[8] | ||||

| Khachig Idarejian Խաչիկ Իտարէճեան | Killed | Teacher | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Karnik Injijian Գառնիկ Ինճիճեան | Survived[18] | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | Released upon request.[12] | ||

| Aris Israelian (Dkhruni) Արիս Իսրայէլեան (Տխրունի) | 1885 | Died | Dashnak | Teacher, writer | Çankırı | Was in Konya in 1916, died later under unknown circumstances.[18][28] |

| Apig Jambaz Աբիկ Ճամպազ | from Pera[28] | Died[28] | Armenian-Catholic[28] | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] |

| Harutiun Jangülian Յարութիւն Ճանկիւլեան | 1855 in Van | Killed | Hunchak | One of the organizers of the 1890 Kumkapı affray, political activist, member of Armenian National Assembly, published his memoirs in 1913. | Ayaş | Dispatched to Diyarbakir, but executed after Aleppo between Urfa and Severek by Haci Tellal Hakimoglu (Haci Onbasi)[42] – Removed from the Ayaş prison on 5 May and taken under military escort to Diyarbakır along with Daghavarian, Agnouni, Khajag, Minassian and Zartarian to appear before a court martial there and they were, seemingly, murdered by state-sponsored paramilitary groups led by Cherkes Ahmet, and lieutenants Halil and Nazım, at a locality called Karacaören shortly before arriving at Diyarbakır.[13] The murderers were tried and executed in Damascus by Cemal PashaВ сентябре 1915 года эти убийства стали предметом расследования 1916 года, проведенного Османским парламентом во главе с Артином Бошгезенианом , депутатом от Алеппо. |

| Арам Календериан Արամ Գալէնտէրեան | Выжил | Должностное лицо Османского банка [18] | Получил разрешение вернуться. [12] | |||

| Арутюн Калфаян Յարութիւն Գալֆաեան | в Ускюдаре | Умер | Гунчак | Директор колледжа Арханян | Чанкыры | Умер в 1915 году. [13] Не путать с его тезкой, тоже депортированным, но дашнакским членом, который был мэром квартала Бакыркей ( Макрикей ) в Константинополе. |

| Арутюн Калфаян Յարութիւն Գալֆաեան [n 8] | 1870 in Talas | Died in Angora[28] | Dashnak | Lawyer, mayor of Bakırköy (Makriköy) | Çankırı | Died in 1915.[13] Uncle of Nshan Kalfayan.[28] Not to be confused with his namesake, also a deportee but a Hunchak member, who was a schoolmaster. |

| Nshan Kalfayan Նշան Գալֆաեան | 16 April 1865 in Üsküdar[43] | Survived | Agronomist, lecturer in agriculture at Berberyan school[39] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] Moved to Greece in 1924. Invited to Persia in 1927 to administer properties of the Shah. Was a correspondent for the Académie française.[28] | |

| Kantaren[28] Գանթարեն | Çankırı | |||||

| Rafael Karagözian Ռաֆայէլ Գարակէօզեան | Survived | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople by a telegramme from Talat Pasha on 7 May 1915.[37] | |||

| Takvor Karagözian(?) Թագւոր Գարակէօզեան | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | ||||

| Vartan Kahanay Karagözian Վարդան Քհնյ. Գարակէօզեան | 15 July 1877 in Kumkapı, Constantinople | Survived | Clergyman from Feriköy | Çankırı | Departed from Çankırı in winter after seven months and survived the next three years as refugee in Uşak together with his companions Hovhan Vartaped Garabedian, Kaspar Cheraz, Mikayel Shamtanchian. After the armistice he returned to Constantinople.[8] | |

| Aristakes Kasparian Արիստակէս Գասպարեան | 1861 in Adana | Killed | Lawyer, businessman, member of Armenian National Assembly | Ayaş[21] | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Husig A. Kahanay Katchouni Յուսիկ Ա. Քհնյ. Քաջունի | 1851 in Arapgir | Died | Dashnak[28] | Clergyman | Çankırı | Deported further and died from illness in a village near Meskene. He died at the same time in the same tent as Yervant Chavushyan.[18] |

| Kevork Kayekjian Գէորգ Գայըգճեան | Killed | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, который покинул Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убит по пути в Йозгат. [34] Трое братьев Кайекджиан были депортированы и вместе убиты недалеко от Ангоры. [28] | ||

| Левон Кайекджян Լեւոն Գայըգճեան | Убит | Торговец [28] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, который покинул Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убит по пути в Йозгат. [34] Трое братьев Кайекджиан были депортированы и вместе убиты недалеко от Ангоры. [28] | ||

| Мигран Кайекджян Միհրան Գայըգճեան | Убит | Торговец [28] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, который покинул Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убит по пути в Йозгат. [34] Трое братьев Кайекджиан были депортированы и вместе убиты недалеко от Ангоры. [28] | ||

| Аршак Каханай Казазян Արշակ Քհնյ. Գազազեան | Выжил [18] | Священнослужитель | Чанкыры | |||

| Пюзант Кечян Բիւզանդ Քէչեան | 1859 г. | Выжил | Редактор, владелец влиятельной газеты Piuzantion , историк | Чанкыры | Permitted to return to Constantinople by special telegramme from Talat Pasha on 7 May 1915.[37][38] The eight prisoners of this group were notified on Sunday, 9 May 1915, about their release[38] and left Çankırı on 11 May 1915.[30] Returned to Constantinople on 1 May 1915 [old calendar](?) and stayed in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, until the end of the war,[n 9] died in 1927[39] or 1928.[28] | |

| Vahan Kehiayan (Dökmeji Vahan) Վահան Քէհեաեան | 1874 in Urfa | Killed | Hunchak | Patriot or educator[8] and craftsman[28] | Çankırı | Убит 26 августа 1915 года вместе с Рубеном Севаком, Даниэлем Варужаном, Онником Магазаджяном, Артином Кочо. [28] |

| Диран Келекян Տիրան Քէլէկեան | 1862 г. Кайсери | Убит | Рамгавар [18] | Писатель, профессор университета, издатель популярной газеты на турецком языке « Сабах » [44] масон , автор французско-турецкого словаря, который до сих пор остается справочным. [45] | Чанкыры | Permitted to reside with his family anywhere outside Constantinople by special order from Talat Pasha on 8 May 1915,[46] chose Smyrna, but was taken under military escort to Çorum to appear before a court martial and killed on 20 October 1915 on the way to Sivas between Yozgat and Kayseri near the bridge Cokgöz on the Kizilirmak.[34] |

| Akrig Kerestejian Ագրիկ Քերեսթեճեան | 1855 in Kartal | Died[28] | Merchant of wood[28] (coincides with the literal meaning of his name) | |||

| Garabed Keropian Պատ. Կարապետ Քերոբեան | from Balıkesir[8] | Survived | Pastor[n 10] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople by special telegramme from Talat Pasha on 7 May 1915.[37] The eight prisoners of this group were notified on Sunday, 9 May 1915, about their release[38] and left Çankırı on 11 May 1915.[30] He went to America.[8] | |

| Mirza Ketenjian Միրզա Քեթենենճեան | Survived[18] | Dashnak | ||||

| Karekin Khajag born as Karekin Chakalian Գարեգին Խաժակ (Գարեգին Չագալեան) | 1867 in Alexandropol | Killed | Dashnak | Newspaper editor, teacher. | Ayaş | Removed from the Ayaş prison on 5 May and taken under military escort to Diyarbakır along with Daghavarian, Agnouni, Jangülian, Minassian and Zartarian to appear before a court martial there and they were, seemingly, murdered by state-sponsored paramilitary groups led by Cherkes Ahmet, and lieutenants Halil and Nazım, at a locality called Karacaören shortly before arriving at Diyarbakır.[13] The murderers were tried and executed in Damascus by Cemal Pasha in September 1915, and the assassinations became the subject of a 1916 investigation by the Ottoman Parliament led by Artin Boshgezenian, the deputy for Aleppo. |

| A. Khazkhazian Ա. Խազխազեան | Merchant[8] | |||||

| Kherbekian Խերպէկեան | from Erzurum | Merchant[12] | Konya | Granted permission to return.[12] | ||

| Hovhannes Kilijian Յովհաննէս Գըլըճեան | Killed | Bookseller[21] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Sarkis Kiljian (S. Srents) Սարգիս Գըլճեան (Ս. Սրենց) | Survived | Dashnak | Teacher, writer, publicist | Çankırı | Escaped from Çankırı to Konya and became Deputy of the Armenian National Assembly in 1919.[28] | |

| Hovhannes Kımpetyan(Kmpetian) Յովհաննէս Գմբէթեան | 1894 in Sivas | Killed | Armenian poet and educator[41] | Çankırı | Killed during the deportation in Ras al-Ain.[41] | |

| Artin Kocho (Harutiun Pekmezian) Գոչօ Արթին (Յարութիւն Պէքմէզեան) | Killed | Bread seller in Ortaköy[28] | Çankırı | Killed by 12 çetes on 26 August 1915 6 hours after Çankırı near the han of Tüneh in a group of five.[28] | ||

| Kevork or Hovhannes Köleyan Գէորգ կամ Յովհաննէս Քէօլէեան | Killed | Çankırı | Killed near Angora.[18] | |||

| Nerses (Der-) Kevorkian Ներսէս (Տէր-) Գէորգեան | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | Was betrayed by a competitor.[28] | |||

| Komitas Կոմիտաս | 1869 in Kütahya | Survived | Священник, композитор, этномузыковед , основатель ряда хоров [n 11] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь специальной телеграммой от Талат-паши 7 мая 1915 года. [37] Восемь заключенных этой группы были уведомлены в воскресенье, 9 мая 1915 года, об их освобождении [38] и покинули Чанкыры 11 мая 1915 года [30] - развил тяжелую форму посттравматического стрессового расстройства и провел двадцать лет в фактическом молчании в психиатрических больницах, умер в 1935 году в Париже. [38] | |

| Арутюн Конялян Յարութիւն Գօնիալեան | Убит | Портной [21] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | ||

| Акоп Кориан Յակոբ Գորեան | from Akn, in his seventies[28] | Survived | Merchant, occasionally a teacher[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] He left Çankırı on 6 August 1915, was jailed in Angora, was displaced to Tarson, arrived in Constantinople on 22 September 1915.[28] | |

| Kosmos[28] Կոզմոս | Çankırı | |||||

| Shavarsh Krissian Շաւարշ Քրիսեան | 1886 in Constantinople | Killed | Dashnak[21] | Writer, publicist,[8] teacher,[21] editor of the first sports magazine of the Ottoman Empire Marmnamarz[47] | Ayaş | Он организовал занятия в спортзале в Аяше. Пока депортированные из Аяша не узнали о 20 гунчакских виселицах 15 июня 1915 года, они не осознавали серьезности своего положения. [42] Турецкие охранники смотрели на учения с большим подозрением. [16] Шаварш Криссиан был убит в Ангоре. [21] |

| М. Кундакджян Մ. Գունտագճեան | Юрист [8] | |||||

| Левон Ларенц (Кирищиян) Լեւոն Լարենց Քիրիշճեան | 1882 г. в Константинополе | Убит | Гунчак | Поэт, переводчик, профессор литературы. | Айаш | Погиб при депортации в Ангору. [21] [29] |

| Онник Магазаджян Օննիկ Մաղազաճեան | 1878 г. в Константинополе | Убит | Председатель Прогрессивного общества Кумкапы | Картограф, книготорговец | Чанкыры | «Разрешено свободно проживать в Чанкыры», согласно телеграмме из Министерства внутренних дел от 25 августа 1915 года по поводу изгнанников, ошибочно не упомянутых в телеграмме от 3 августа. [40] Убит в деревне Тюней в 1915 году вместе с Рубеном Севаком, Даниэлем Варужаном и Гюлистанианом [13] в группе из пяти человек. [34] |

| Асдвадзадур Манесян (Маниасец) Աստուածատուր Մանեսեան | Выжил [18] | Торговец [28] | Чанкыры | |||

| Бедрос Маникян Պետրոս Մանիկեան | Выжил [18] | Чанкыры | Фармацевт [28] | |||

| Вртанес Мардигуян Վրթանէս Մարտիկեան | Выжил | Айаш | Deported in a group of 50 persons to Angora, 5 May 1915, dispatched to Ayaş on 7 May 1915, set free in July 1915,[42] returned to Constantinople.[21] | |||

| Marzbed (Ghazar Ghazarian) Մարզպետ (Ղազար Ղազարեան) | Died | Dashnak | Teacher | Ayaş | Dispatched around 18 May 1915 to Kayseri to appear before a court martial,[42] worked under fake Turkish identity for the Germans in Intilli (Amanus railway tunnel), escaped to Nusaybin where he fell from a horse and died right before the armistice.[21] | |

| A. D. Mateossian Ա. Տ. Մատթէոսեան | Lawyer, writer[8] | |||||

| Melik Melikian[28] Մելիք Մելիքեան | Killed | Çankırı | ||||

| Simon Melkonian Սիմոն Մելքոնեան | из Ортакёй [28] | Выжил [28] | Архитектор [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | |

| Теодорос Мензикян Թ . Մենծիկեան | Убит | Торговец [8] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | ||

| Саркис Минасян родился как Арам Ашот Սարգիս Մինասեան | 1873 г. в Шенгилере, Ялова | Убит | Дашнак [21] | Главный редактор Дрошака [21] , редактор армянской газеты в Бостоне до 1909 года, педагог, писатель и политический деятель в османской столице после 1909 года; депутат Национального Собрания Армении [33] | Айаш | Removed from the Ayaş prison on 5 May and taken under military escort to Diyarbakır along with Daghavarian, Agnouni, Jangülian, Khajag and Zartarian to appear before a court martial there and they were, seemingly, murdered by state-sponsored paramilitary groups led by Cherkes Ahmet, and lieutenants Halil and Nazım, at a locality called Karacaören shortly before arriving at Diyarbakır.[13] The murderers were tried and executed in Damascus by Cemal Pasha in September 1915, and the assassinations became the subject of a 1916 investigation by the Ottoman Parliament led by Artin Boshgezenian, the deputy for Aleppo. |

| Krikor Miskjian Գրիգոր Միսքճեան | 1865 | Killed[28] | brother of Stepan Miskjian[28] | Pharmacist[28] | Çankırı | Belonged to the second convoy with only one[6] or two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat,[34] killed near Angora.[18][28] |

| Stepan Miskjian Ստեփան Միսքճեան | 1852 in Constantinople | Killed[28] | brother of Krikor Miskjian[28] | Physician[28] | Çankırı | Belonged to the second convoy with only one[6] or two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat,[34] killed near Angora.[18][28] |

| Zareh Momjian Զարեհ Մոմճեան | Killed | Translator at the Russian Consulate | Çankırı | "Pardoned on condition on not returning to Constantinople" according to a telegramme from the Ministry of the Interior on 25 August 1915 on the subject of exiles erroneously unlisted in a former 3 August telegramme.[40] Belonged to the second convoy with only two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat.[34] | ||

| Apig Mübahejian Աբիկ Միւպահեաճեան | Survived | Publicist | Konya | Granted permission to return.[12] | ||

| Avedis Nakashian Աւետիս Նագաշեան | Survived | Physician | Ayaş | Was set free 23 July 1915, sent his family to Bulgaria, served in the Ottoman army as captain in the Gülhane Hospital at the time of the Gallipoli campaign and immigrated to the US.[16] | ||

| Nakulian Նագուլեան | Survived | Doctor | Ayaş | Exiled 3 May 1915. Allowed to move free in Ayaş. Returned later to Constantinople.[13] | ||

| Hagop Nargilejian Յակոբ Նարկիլէճեան | Survived | Pharmacist in the army[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople by special telegramme from Talat Pasha on 7 May 1915.[37] The eight prisoners of this group were notified on Sunday, 9 May 1915, about their release[38] and left Çankırı on 11 May 1915.[30] | ||

| Markos Natanian Մարկոս Նաթանեան | Survived | Member of Armenian National Assembly[33] | Çorum | Survived deportation to Çorum and later to Iskiliben, was permitted to go back.[12] | ||

| Hrant Nazarian Հրանդ Նազարեան | Çankırı | |||||

| Serovpe Noradungian Սերովբէ Նորատունկեան | Killed | Dashnak | Teacher at the Sanassarian college and member of Armenian National Assembly[21] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Nosrigian Նօսրիկեան | from Erzurum | Survived | Merchant | Konya | Granted permission to return.[12] | |

| Nshan Նշան | Killed | Tattooist in Kumkapı[21] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Nshan Odian Նշան Օտեան | Hunchak[42] | Ayaş | ||||

| Yervant Odian Երուանդ Օտեան | 1869 in Constantinople | Survived | Writer | Ayaş | Deported August 1915. Accompanied Karekin Vrtd. Khatchaturian (prelate of Konia) from Tarson to Osmanieh.[48] Islamized in 1916 under the name Aziz Nuri[12] in Hama. After failed attempts to escape from Der Zor, Odian worked in a factory for military uniforms together with Armenian deportees from Aintab. Soon afterwards he became translator to the military commander of Der Zor. Finally he was orderly to the commander Edwal of the German garrison in Der Zor and gave account of the killing of the last deportees from Constantinople in the prison of Der Zor as late as January 1918 and described that all the policemen and officials kept Armenian women.[49] | |

| Aram Onnikian Արամ Օննիկեան | Survived[18] | Merchant,[8] chemist[18] | Çankırı | Son of Krikor Onnikian | ||

| Hovhannes Onnikian Յովհաննէս Օննիկեան | Died | Merchant[8] | Çankırı | Son of Krikor Onnikian; died from illness in Hajkiri near Çankırı.[18] | ||

| Krikor Onnikian Գրիգոր Օննիկեան | 1840 | Died | Merchant[8] | Çankırı | Father of Aram, Hovhannes and Mkrtich Onnikian; died from illness in Çankırı.[18] | |

| Mkrtich Onnikian Մկրտիչ Օննիկեան | Died | Merchant[8] | Çankırı | Son of Krikor Onnikian; died in Der Zor.[18] | ||

| Panaghogh Փանաղող | Writer, publicist[8] | |||||

| Shavars Panossian Շաւարշ Փանոսեան | Survived | Teacher from Pera.[12] | Ayaş | Granted permission to return.[12] | ||

| Nerses Papazian (Vartabed Mashtots) Ներսէս Փափազեան | Killed | Dashnak | Editor of Azadamard,[21] Patriot or educator[8] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Vrtanes Papazian Վրթանէս Փափազեան | Survived | Tailor[12] | Çankırı | Wrongly deported as he bore the same name as the novelist who escaped to Bulgaria and later to Russia.[12] Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] | ||

| Ardashes Parisian Արտաշես Փարիսեան | Survived[18] | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | |||

| Parseghian Բարսեղեան | Survived | Ayaş | Granted permission to return.[12] | |||

| Арменаг Парсегян Արմենակ Բարսեղեան | Выжил [28] | Дашнак [28] | Учитель, изучал философию в Берлине, жил в Пера [28] | Чанкыры | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь вскоре после 11 мая 1915 г. [30] | |

| Г. Парсегян Յ. Բարսեղեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Кегам Парсегян Գեղամ Բարսեղեան | 1883 г. в Константинополе | Убит | Дашнакский | Писатель, публицист, [8] редактор, педагог [21] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] |

| Саркис Парсегян (Шамиль) Սարգիս Բարսեղեան (Շամիլ) | Убит [28] | Патриот или педагог [8] | Айаш | |||

| Гарабед Пашаян Хан Կարապետ Փաշայեան Խան | 1864 г. в Константинополе | Убит | Дашнакский | Врач, писатель [8] бывший депутат османского парламента, депутат Национального собрания Армении [21] | Айаш | Сначала замучили [50], а потом убили в Ангоре. [21] |

| М. Пиосян Մ. Փիոսեան | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Зампад Пюрад Дер- Газарянц Սմբատ Բիւրատ Տէր-Ղազարեանց | 1862 год в Зейтуне ( сегодня Сулейманлы ) | Умер | Писатель, общественный деятель, депутат Национального Собрания Армении [21] | Айаш [21] | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |

| Г. Рейсиан Կ . Րէյիսեան | Торговец [8] | |||||

| Rostom (Riustem Rostomiants) Րոստոմ (Րիւսթէմ Րոստոմեանց) | Killed | Merchant[8] and public figure[21] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Vramshabuh Samueloff Վրամշապուհ Սամուէլօֆ | Killed | Merchant[8] Armenian from Russia, banker | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Sarafian[28] Սարաֆեան | Çankırı | |||||

| Garabed Sarafian Կարապետ Սարաֆեան | Killed | Public official | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Sato Սաթօ | Patriot or educator[8] | |||||

| Jacques Sayabalian (Pailag) Ժագ Սայապալեան (Փայլակ) | 1880 in Konya | Killed | Armenian National Assembly | Interpreter for the British Consul in Konya between 1901 and 1905, then vice-consul for a year and a half. After 1909, journalist in the capital. | Çankırı | Killed in Angora.[21] |

| Margos Sefer Մարկոս Սեֆեր | Survived | Lawyer[21] | Ayaş | Deported in place of Markos Natanian and returned to Constantinople.[21] | ||

| Vartkes Serengülian Վարդգէս Սէրէնկիւլեան | 1871 in Erzurum | Killed | Deputy in the Ottoman parliament | Dispatched to Diyarbakır to appear before a court martial | Deported 21 May 1915[51] or 2 June 1915.[52] Same fate as Krikor Zohrab.[53] (Cherkes Ahmet and Halil were led to Damascus and executed there on orders from Cemal Pasha, in connection with the murder of the two deputies, on 30 September 1915, Nazım had died in a fight before that.) | |

| Багдасар Саркисян Պաղտասար Սարգիսեան | Выжил | Чанкыры | «Помилован при условии невозвращения в Константинополь», согласно телеграмме из Министерства внутренних дел от 25 августа 1915 года о ссыльных, ошибочно не упомянутых в телеграмме от 3 августа. [40] | |||

| Маргос Сервет Эффенди (Прудиан) Մարկոս Սէրվէթ | Выжил | Юрист из Картала [12] | Айаш | Получил разрешение вернуться. [12] | ||

| Рубен Севак Ռուբէն Սեւակ | 1885 г. в Силиври | Убит | Врач, выдающийся поэт и писатель, бывший капитан Османской армии во время Балканских войн . | Чанкыры | Депортирован 22 июня 1915 года [54] , но ему «разрешили свободно проживать в Чанкыры» в соответствии с телеграммой Министерства внутренних дел от 25 августа 1915 года по поводу изгнанников, ошибочно не упомянутых в телеграмме от 3 августа. [40] Убит в селе Тюней в 1915 году вместе с Гюлистаняном, Даниэлем Варужаном и Махазаджяном [13] в группе из пяти человек. [34] Его дом в Эльмадаги , Константинополь , теперь музей. [55] | |

| Шахбаз [n 12] Շահպազ | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Парсех Шахбаз Բարսեղ Շահպազ | 1883 год, Бояджикёй, Константинополь . | Убит | Дашнакский | Lawyer,[21] journalist, columnist | Çankırı | "Murdered on Harput-Malatya road."[13][21] On 6 July 1915, in a letter to Miss. Zaruhi Bahri and Evgine Khachigian, Parsegh Shahbaz wrote from Aintab that due to his wounded feet and stomachaches, he will rest for 6–7 days until he has to continue the 8–10 days journey to M. Aziz. But he had no idea why he was sent there.[12] According to Vahe-Haig (Վահէ-Հայկ), survivor of the massacre of Harput, Parsegh Shahbaz was jailed 8 days after the massacre in the central prison of Mezre. Parsegh Shahbaz remained without food for a week and was severely beaten and finally killed by gendarmes under the wall of 'the factory'.[12] |

| A. Shahen Ա. Շահէն | Patriot or educator[8] | |||||

| Yenovk Shahen Ենովք Շահէն | 1881 in Bardizag (near İzmit) | Killed | Actor[8] | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Sarkis Shahinian Սարգիս Շահինեան | Survived | Çankırı | "Pardoned on condition on not returning to Constantinople" according to a telegramme from the Ministry of the Interior on 25 August 1915 on the subject of exiles erroneously unlisted in a former 3 August telegramme.[40] | |||

| Harutiun Shahrigian (Adom) Յարութիւն Շահրիկեան (Ատոմ) | 1860 in Shabin-Karahisar | Killed | Dashnak | Dashnak leader, lawyer, member of Armenian National Assembly. | Ayaş[21][28] | First tortured[50] and then killed in Angora.[21] |

| Levon Shamtanchian Լեւոն Շամտանճեան | Survived | Ayaş | Deported in lieu of Mikayel Shamtanchian, returned to Constantinople.[12][21] | |||

| Mikayel Shamtanchian Միքայէլ Շամտանճեան | 1874 | Survived | Friend of Dikran Chökürian | Newspaper editor at Vostan, writer, lecturer, leader in the Armenian National Assembly | Çankırı | Уехал из Чанкыры зимой через семь месяцев и пережил следующие три года в качестве беженца в Ушаке вместе со своими товарищами Овханом Вартапедом Гарабедяном, Каспаром Черазом, Варданом Каханай Карагезяном из Ферикёй. После перемирия вернулся в Константинополь. [8] Опубликовал воспоминания о послевоенной ссылке. [13] - г. 1926 [39] |

| Левон Шашян Լեւոն Շաշեան | Убит | Торговец [8] | Убит в Дер Зоре. [12] | |||

| Сиаманто (Адом Ерджанян) Սիամանթօ (Ատոմ Եարճանեան) | 1878 г. в Акне | Убит | Дашнак [21] | Поэт, писатель, депутат Национального Собрания Армении [21] | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |

| Krikor Siurmeian Գրիգոր Սիւրմէեան | Survived | Father of Artavazd V. Siurmeian.[12] | Ayaş | Granted permission to return to Constantinople.[12] | ||

| Onnig Srabian (Onnig Jirayr) Օննիկ Սրապեան (Օննիկ Ժիրայր) | 1878 in Erzincan | Killed | Teacher | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |

| Yeghia Sughikian Եղիա Սուղիկեան | Writer, publicist[8] | Met Yervant Odian and Aram Andonian in September 1915 while working in the mill of Aram and Ardashes Shalvarjian in Tarson (supplying daily 30,000 Ottoman soldiers with flour).[48] | ||||

| S. Svin Ս. Սուին | Patriot or educator[8] | 24 April 1915 | ||||

| Mihran Tabakian Միհրան Թապագեան | 1878 from Adapazar[28] | Killed | Dashnak[28] | Teacher and writer[28] | Çankırı | Belonged to the second convoy with only one[6] or two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat.[34] |

| Garabed Tashjian Կարապետ Թաշճեան | Killed | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] | |||

| Garabed Tashjian Կարապետ Թաշճեան | Survived | Butcher[28] | Çankırı | Deported in lieu of Garabed Tashjian jailed in Ayaş, released and returned to Constantinople.[28] | ||

| Stepan Tatarian Ստեփան Թաթարեան | Survived[28] | Merchant[28] | Çankırı | Dispatched to Kayseri to appear before a court martial (where he was an eyewitness to executions[12]). Joined by a group of four from Ayaş beginning of July.[30] Survived deportation from Çankırı to Kayseri to Aleppo and returned to Constantinople after the armistice.[28] | ||

| Kevork Terjumanian Գէորգ Թէրճիմանեան | Killed | Ayaş | Merchant[8] | Killed in Angora.[21] | ||

| Ohannes Terlemezian Օհաննես Թէրլէմէզեան | from Van | Survived[28] | Money changer[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] One of the last who was released from Çankırı. He left Çankırı on 6 August 1915, was jailed in Angora, came to Tarson, arrived in Constantinople on 22 September 1915.[28] | |

| Hagop Terzian Յակոբ Թէրզեան | 1879 in Hadjin | Killed | Hunchak | Pharmacist | Çankırı | Belonged to the second convoy with only one[6] or two survivors that left Çankırı on 19 August 1915, jailed in Angora 20–24 August killed en route to Yozgat,[34] killed near Angora.[18] |

| Haig Tiriakian Հայկ Թիրեաքեան | about 60 years old[21] | Survived | Cashier of Phoenix[12] | Ayaş | Deported instead of his Dashnak homonym. Returned to Constantinople.[12][21] | |

| Haig Tiriakian Հայկ Թիրեաքեան (Հրաչ) | 1871 in Trabzon | Killed | Dashnak | Member of Armenian National Assembly[21] | Çankırı[21] | After learning that another Haig Tiriakian had been detained in Ayaş he demanded his namesake's release and his own transfer from Çankırı to Ayaş. He was later killed in Angora.[21] |

| Yervant Tolayan Երուանդ Թօլայեան | 1883 | Survived | Theater director, playwright, editor of the satirical journal Gavroche | Çankırı | Разрешено вернуться в Константинополь специальной телеграммой от Талат-паши 7 мая 1915 года. [37] [38] Восемь заключенных этой группы были уведомлены в воскресенье, 9 мая 1915 года, об их освобождении [38] и покинули Чанкыры 11 мая 1915 года. [ 30] Ервант Толаян умер в 1937 году . [39] | |

| Акоп Топджян Յակոբ Թօփճեան | 1876 г. | Выжил | Рамгавар | Редактор [n 13] | Чанкыры | Разрешив вернуться в Константинополь в середине июня 1915 года, [13] умер в 1951 году [39] . |

| Торком Թորգոմ | Патриот или педагог [8] | |||||

| Ваграм Торкомян Վահրամ Թորգոմեան | 20 апреля 1858 г. [56] в Константинополе . | Выжил | Physician,[n 14] medical historian | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople by special telegramme from Talat Pasha on 7 May 1915.[37] The eight prisoners of this group were notified on Sunday, 9 May 1915, about their release[38] and left Çankırı on 11 May 1915.[30] He moved to France in 1922.[39] He published a book after the war (a list of Armenian doctors) in Évreux, France in 1922 and a study on Ethiopean Taenicide-Kosso[57] in Antwerp in 1929. He died 11 August 1942 in Paris.[58] | |

| Samvel Tumajan (Tomajanian) Սամուել Թումաճան (Թոմաճանեան) | Died[28] | Hunchak[28] | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] Samvel Tomajian/Թօմաճեան (!) died according to Alboyajian.[28] | ||

| Daniel Varoujan Դանիէլ Վարուժան | 1884 in Brgnik (near Sivas) | Killed | Poet | Çankırı | Killed together with Ruben Sevak by 12 çetes on 26 August 1915 six hours after Çankırı near the han of Tüneh in a group of five.[34] | |

| Aram Yerchanik Արամ Երջանիկ | 1865 | Died | Restaurant owner | Çankırı | Deported because many intellectuals regularly met at his restaurant in Bahçekapı, died in 1915.[28] | |

| D. Yerganian Տ. Երկանեան | Lawyer[8] | |||||

| Крикор Есаян Գրիգոր Եսայեան | 1883 год из Вана [28] | Убит [34] | Дашнак [28] | Учитель французского языка и математики, переводчик книги Левона Шанта «Древние боги» на французский язык [28] | Чанкыры | Принадлежал ко второму конвою с одним [6] или двумя выжившими, который покинул Чанкыры 19 августа 1915 года, заключен в тюрьму в Ангоре 20–24 августа, убит по пути в Йозгат. [34] |

| Езник Եզնիկ | Профессия | Чанкыры [28] | ||||

| Нерсес Закарян Ներսէս Զաքարեան | Убит | Гунчак [21] | Патриот или просветитель, [8] депутат Национального Собрания Армении [21] | Айаш | Погиб в Ангоре. [21] | |

| Avedis Zarifian Աւետիս Զարիֆեան | Survived[18] | Pharmacist | Çankırı | Permitted to return to Constantinople soon after 11 May 1915.[30] | ||

| Rupen Zartarian Ռուբէն Զարդարեան | 1874 in Kharpert | Killed | Writer, poet, newspaper (Azadamard) and textbook editor, considered a pioneer of Armenian rural literature. Translated Victor Hugo, Maxim Gorki, Anatole France, Oscar Wilde into Armenian.[29] | Ayaş | Выведены из тюрьмы Айаш 5 мая и доставлены под военным конвоем в Диярбакыр вместе с Дагаваряном, Агнуни, Джангюляном, Хаджагом и Минасяном, чтобы предстать перед военным трибуналом, и они, по-видимому, были убиты спонсируемыми государством военизированными группами во главе с Черкесом Ахметом. , и лейтенанты Халил и Назим в местности под названием Караджаорен незадолго до прибытия в Диярбакыр . [13] Убийцы были преданы суду и казнены в Дамаске Джемаль -пашой в сентябре 1915 года, и убийства стали предметом расследования 1916 года, проведенного Османским парламентом во главе сArtin Boshgezenian, the deputy for Aleppo. | |

| Zenop[28] Զենոբ | Çankırı | |||||

| Krikor Zohrab Գրիգոր Զօհրապ | 1861 in Constantinople | Killed | Writer, jurist, deputy in the Ottoman parliament | Dispatched to Diyarbakır to appear before a court martial | Депортирован либо 21 мая 1915 года, либо 2 июня 1915 года. [52] Приказано предстать перед военным трибуналом в Диярбакыре вместе с Варткесом Оганесом Серенгуляном, оба отправились в Алеппо поездом в сопровождении одного жандарма, оставались в Алеппо на несколько недель, ждали. результаты безуспешных попыток османского губернатора города отправить их обратно в Константинополь (в некоторых источниках упоминается , что сам Джемаль-паша вмешался в их возвращение, но Талат-паша настаивает на отправке их в военный трибунал ), а затем отправили в Урфу and remained there for some time in the house of a Turkish deputy friend, taken under police escort and led to Diyarbakır by car -allegedly accompanied on a voluntary basis by some notable Urfa Armenians, and with many sources confirming, they were murdered by state-sponsored paramilitary groups led by Cherkes Ahmet, Halil and Nazım, at a locality called Karaköprü or Şeytanderesi in the outskirts of Urfa, some time between 15 July and 20 July 1915. The murderers were tried and executed in Damascus by Cemal Pasha in September 1915, and the assassinations became the subject of a 1916 investigation by the Ottoman Parliament led by Artin Boshgezenian, the deputy for Aleppo. | |

| Partogh Zorian (Jirayr) Բարթող Զօրեան (Ժիրայր) | 1879 in Tamzara | Killed | Dashnak | Publicist | Ayaş | Killed in Angora.[21] |

Notes

- ^ According to Teotig's year book 1916–20 these were: Dikran Ajemian, Mkrtich Garabedian, H. Asadurian, Haig Tiriakian, Shavarsh Panossian, Krikor Siurmeian, Servet, Dr. Parseghian, Piuzant Bozajian, and Dr. Avedis Nakashian.

- ^ According to Teotig's year book 1916–20 these were: Dikran Ajemian, Mkrtich Garabedian, H. Asadurian, Haig Tiriakian, Shavarsh Panossian, Krikor Siurmeian, Servet, Dr. Parseghian, Piuzant Bozajian, and Dr. Avedis Nakashian.

- ^ According to Teotig's year book 1916–20 these were: Dikran Ajemian, Mkrtich Garabedian, H. Asadurian, Haig Tiriakian, Shavarsh Panossian, Krikor Siurmeian, Servet, Dr. Parseghian, Piuzant Bozajian, and Dr. Avedis Nakashian.

- ^ Western Armenian orthography is used throughout the article as the deportees mother language and eyewitness accounts are all Western Armenian.

- ^ «Из какого-то места» (например, из Вана, из Кайсери) означает место происхождения, то есть гражданин, живущий в Константинополе, часто отождествлялся с местом происхождения его семьи.

- ↑ Крикор Балакян в своих мемуарах ошибочно записал как «Барсамян» .

- ↑ Теотик перечисляет М. Степаняна (купца).

- ↑ Теотик и Балакян перечисляют двух Б. Калфаян или Бедрос Калфаян соответственно, оба убитых в Ангоре (заключенных в тюрьму в Аяше, согласно Гарине Авакян). Один из них был мэром Бакыркёй (Макрикёй) и Дашнака, другой - торговцем, которого депортировали и по ошибке убили.

- ^ Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan was amazed how Piuzant Kechian received permission to get free from detention, and repeats assumptions about him being a spy for the Young Turks.[22]

- ^ Studied at the theological seminary of Merzifon, worked for the Bible House founded by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.

- ^ He was also the music teacher of prince Mejid's wife.

- ^ Not to be confused with Parsegh Shahbaz (listed among the "writers, publicists" on Teotig's list).

- ^ Edited a catalogue of the manuscripts of the monastery of Armaş, posthumously Venice 1962.

- ^ He was also the physician of Patriarch Zaven Der Yeghiayan and Prince Mejid.

References

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2013). "The Armenian Genocide". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William Spencer (eds.). Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-415-87191-4.

- ^ Blinka, David S. (2008). Re-creating Armenia: America and the memory of the Armenian genocide. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 31.

In what scholars commonly refer to as the decapitation strike on April 24, 1915...

- ^ Bloxham, Donald (2005). The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction of the Ottoman Armenians. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0.

...the decapitation of the Armenian nation with the series of mass arrests that began on 24 April...

- ^ Сахакян, TA (2002). «Արևմտահայ մտավորականության սպանդի արտացոլումը հայ մամուլում 1915–1916 թթ. [Интерпретация факта истребления армянской интеллигенции в армянской прессе в 1915–1916 годах]» . Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (на армянском языке) (1): 89.

Դրանով թուրքական կառավարությունը ձգտում էր արևմտահայությանը գլխատել, նրան զրանյ ,կվարհր:

- ^ Ширакян, Аршавир (1976). Կտակն էր Նահաակներուն [Гдагн эр Нахадагнерин] [ Наследие: Мемуары армянского патриота ]. перевод Ширакяна, Соня. Бостон: Hairenik Press . OCLC 4836363 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ternon, Yves (1989). Enquête sur la négation d'un génocide (in French). Marseille: Éditions Parenthèses. p. 27. ISBN 978-2-86364-052-4. LCCN 90111181.

- ^ a b Walker, Christopher J. (1997). "World War I and the Armenian Genocide". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times. II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-333-61974-2. OCLC 59862523 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw топор ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh Teotoros LapçinciyanԳողգոթա հայ հոգեւորականութեան [Голгофа армянского духовенства], Константинополь, 1921 г.[ссылка 1]

- Перейти ↑ Der Yeghiayan 2002 , p. 63.

- Перейти ↑ Panossian , Razmik (2006). Армяне. От королей и священников до купцов и комиссаров . Нью-Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета. п. 237 . ISBN 978-0-231-13926-7. LCCN 2006040206 . OCLC 64084873 .

- Перейти ↑ Bournoutian, George A. (2002). Краткая история армянского народа . Коста-Меса, Калифорния: Mazda. п. 272 . ISBN 978-1-56859-141-4. LCCN 2002021898. OCLC 49331952.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap Теоторос Лапчинцян ( Теотиг ): Ամէնուն Տարեցոյցը. Ժ-ԺԴ. Տարի. 1916–1920 гг. [Альманах обывателя. 10.-14. Год. 1916–1920] , Г. Кешишян пресс, Константинополь, 1920.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Богосян, Хачиг (21 апреля 2001 г.). «Мой арест и ссылка 24 апреля 1915 года». Армянский репортер .

- ^ a b Дадриан, Ваакн Н. (2003). История геноцида армян: этнический конфликт от Балкан до Анатолии и Кавказа (6-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Книги Бергана. п. 221. ISBN . 1-57181-666-6.

- ^ John Horne, ed. (2012). A companion to World War I (1. publ. ed.). Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 191. ISBN 978-1119968702.

- ^ a b c Nakashian, Avedis; Rouben Mamoulian Collection (Library of Congress) (1940). A Man Who Found A Country. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 208–278. LCCN 40007723. OCLC 382971.

- ^ Der Yeghiayan 2002, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Palak'ean, Grigoris (2002). Le Golgotha arménien: de Berlin à Deir-es-Zor (in French). 1. La Ferté-sous-Jouarre: Le Cerle d'Écrits Caucasiens. pp. 95–102. ISBN 978-2-913564-08-4. OCLC 163168810.

- ^ Shamtanchean, Mikʻayēl (2007) [1947]. Hay mtkʻin harkě egheṛnin [The Fatal Night. An Eyewitness Account of the Extermination of Armenian Intellectuals in 1915]. Genocide library, vol. 2. Translated by Ishkhan Jinbashian. Studio City, California: H. and K. Majikian Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791289-9-8. LCCN 94964887. OCLC 326856085.

- ^ Kévorkian 2006, p. 318.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck Palak'ean, Grigoris (2002). Le Golgotha arménien : de Berlin à Deir-es-Zor (in French). 1. La Ferté-sous-Jouarre: Le Cerle d'Écrits Caucasiens. pp. 87–94. ISBN 978-2-913564-08-4. OCLC 163168810.

- ^ a b Der Yeghiayan 2002, p. 66.

- ^ "The Real Turkish Heroes of 1915". The Armenian Weekly. 29 July 2013.

- ^ Kevorkian, Raymond (3 June 2008). "The Extermination of Ottoman Armenians by the Young Turk Regime (1915–1916)" (PDF). Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. p. 31.

- ^ Odian, Yervant (2009). Krikor Beledian (ed.). Accursed years : my exile and return from Der Zor, 1914–1919. London: Gomidas Institute. p. x. ISBN 978-1-903656-84-6.

- ^ Karakashian, Meliné (24 July 2013). "Did Gomidas 'Go Mad'? Writing a Book on Vartabed's Trauma". Armenian Weekly.

- ^ "At the Origins of Commemoration: The 90th Anniversary Declaring April 24 as a Day of Mourning and Commemoration of the Armenian Genocide". Armenian Genocide Museum. 10 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl Avagyan, Karine (2002). Եղեռնահուշ մասունք կամ խոստովանողք եւ վկայք խաչի [Relic of the Genocide or to those who suffered in the name of the cross and died for their faith] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Zangak 97. ISBN 978-99930-2-436-1. OCLC 62755097.[ref-notes 2]

- ^ a b c d e Article in Yevrobatsi 23 April 2007. "Etre à l'Université du Michigan pour la commemoration du 24 avril 1915", 23-04-2007, Par le Professor Fatma Müge Göçek, Université du Michigan Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Kévorkian 2006, p. 662.

- ^ a b Peroomian, Rubina (1993). Literary Responses To Catastrophe. A Comparison Of The Armenian And Jewish Experience. Studies in Near Eastern culture and society, 8. Atlanta: Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-55540-895-4. LCCN 93026129. OCLC 28547490.

- ^ Andonian, Aram (2007). En ces sombres jours. Prunus armeniaca, 4 (in French). Translated from Armenian by Hervé Georgelin. Genève: MétisPresses. p. 10. ISBN 978-2-940357-07-9. OCLC 470925711.

- ^ a b c Der Yeghiayan 2002, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Kévorkian 2006, p. 663.

- ^ a b Bardakjian, Kevork B. (2000). A Reference Guide to Modern Armenian Literature, 1500–1920. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2747-0. LCCN 98043139. OCLC 39930676.

- ^ Balakian, Krikoris Հայ Գողգոթան [The Armenian Golgotha], Mechitaristenpresse Vienna 1922 (vol. 1) and Paris 1956 (vol. 2)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kastamonu Vilâyeti'ne" (PDF) (in Turkish). State Archives of the Republic of Turkey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kuyumjian 2001, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kevork Pamukciyan: Biyografileriyle Ermeniler, Aras Yayıncılık, Istanbul 2003 OCLC 81958802

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kastamonu Vilâyeti'ne" (in Turkish). State Archives of the Republic of Turkey. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d Göçek, Fatma Müge (2011). The Transformation of Turkey: Redefining State and Society from the Ottoman Empire to the Modern Era. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 220–221. ISBN 9781848856110.

- ^ a b c d e Kévorkian 2006, p. 652.

- ^ Teotig (Teotoros Lapçinciyan): Ամէնուն Տարեցոյցը. 1910. [Everyone's Almanac. 1910], V. and H. Der Nersesian Editions, Constantinople, 1910, p. 318

- ^ Kuyumjian 2001, p. 129.

- ^ Somel, Selcuk Aksin (2010). The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1461731764.

- ^ "That Diran Kelekyan May Reside In Any Province He Wishes Outside Of İstanbul". General Directorate for the State Archives [Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü] (23 C. 1333). 8 May 1915. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Armenian Sport and Gymnastics in the Ottoman Empire". Public Radio of Armenia. 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ a b Teotig (Teotoros Lapçinciyan): Ամէնուն Տարեցոյցը. ԺԶ. Տարի. 1922. [Everyone's Almanac. 16. Year. 1922], M. Hovakimian Press, Constantinople 1922, p. 113

- ^ Kévorkian 2006, p. 825.

- ^ a b Dr. Nakashian according Vrtanès Mardiguian in a letter to Aram Andonian, 26 April 1947

- ^ Ternon, Yves (1990). The Armenians : history of a genocide (2nd ed.). Delmar, N.Y.: Caravan Books. ISBN 0-88206-508-4.

- ^ a b Raymond H. Kévorkian (ed.): Revue d'histoire arménienne contemporaine. Tome 1. 1995 Paris p.254

- ^ El-Ghusein, Fà'iz (1917). Martyred Armenia. p. .

- ^ Kantian, Raffi. Der Dichter und seine Frau. Rupen Sevag & Helene Apell. Ein armenisch-deutsches Paar in den Zeiten des Genozids in: Armenisch-Deutsche Korrespondenz, Nr. 139, Jg. 2008/Heft 1, pp. 46

- ^ "Kristin Saleri'ye "Geçmiş Olsun: Ziyareti". Lraper (in Turkish). 4 March 2006. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- ^ Vahram Torkomian: Mémoires d'un médecin stambouliote. 1860–1890, translated by Simone Denis-Torkomian, edited by Raymond Kévorkian, Centre d'histoire arménnienne contemporaine, Bibliothèque Nubar de l'UGAB 2007, ISSN 1259-4873

- ^ Pankhurst R (July 1979). "Europe's discovery of the Ethiopian taenicide—kosso". Med Hist. 23 (3): 297–313. doi:10.1017/S0025727300051772. PMC 1082476. PMID 395376.

- ^ Raymond Kévorkian (editor): Simone Denis-Torkomian: Les Mémoires du Dr. Vahram Torkomian, p. 14, in: Vahram Torkomian: Mémoires d'un médecin stambouliote. 1860–1890, translated by Simone Denis-Torkomian, edited by Raymond Kévorkian, Centre d'histoire arménnienne contemporaine, Bibliothèque Nubar de l'UGAB 2007, ISSN 1259-4873

Reference notes

- ^ Gives an account of over 1,500 deported clergymen all over the Ottoman Empire with selected biographical entries and lists 100 notables of 24 April 1915 by name out of 270 in total and classifies them roughly in 9 professional groups.

- ^ Gives an account of the events that lead to Çankırı (first deportation stop in Anatolia) and 100 short biographic descriptions of deportees on the basis of a rosary/worry-beads (Hamrich) in the History Museum of Yerevan with the engraved names of the deportees, that a deportee himself, Varteres Atanasian (Nr. 71 of the worry-beads), created.

Bibliography

- Avagyan, Karine (2002). Եղեռնահուշ մասունք կամ խոստովանողք եւ վկայք խաչի [Relic of the Genocide or to those who suffered in the name of the cross and died for their faith] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Zangak 97. ISBN 978-99930-2-436-1. OCLC 62755097.

- Krikor Balakian Հայ Գողգոթան [The Armenian Golgotha], Mechitaristenpresse Vienna 1922 (vol. 1) and Paris 1956 (vol. 2) (a new edition in French: Georges Balakian: Le Golgotha arménien, Le cercle d'écrits caucasiens, La Ferté-Sous-Jouarre 2002 (vol. 1) ISBN 978-2-913564-08-4, 2004 (vol. 2) ISBN 2-913564-13-5)

- Beledian, Krikor (2003). "Le retour de la Catastrophe". In Coquio, Catherine (ed.). L'histoire trouée. Négation et témoignage (in French). Nantes: éditions l'atalante. ISBN 978-2-84172-248-8. [essay about the survivor literature 1918–23]

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2006). Le Génocide des Arméniens [The Armenian Genocide] (in French). Paris: Odile Jacob. ISBN 978-2-7381-1830-1.

- Lapçinciyan, Teotoros (1921). Գողգոթա հայ հոգեւորականութեան [The Golgotha of the Armenian clergy]. Constantinople: H. Mateossian. [Gives an account of over 1.500 deported clergymen all over the Ottoman Empire with selected biographical entries and lists 100 notables of 24 April 1915 by name out of 270 in total and classifies them roughly in 9 professional groups]

- Lapçinciyan, Teotoros (1920). Ամէնուն Տարեցոյցը. Ժ-ԺԴ. Տարի. 1916–1920. [Everyman's Almanac. 10.-14. Year. 1916–1920]. Constantinople: G. Keshishian Press.

- Shamtanchian, Mikayel (2007). The Fatal Night. An Eyewitness Account of the Extermination of Armenian Intellectuals in 1915. Translated by Jinbashian, Ishkhan. Studio City, California: Manjikian Publications. ISBN 978-0-9791289-9-8.

- Kuyumjian, Rita Soulahian (2001). Archeology of Madness. Komitas. Portrait of an Armenian Icon. Princeton, New Jersey: Gomidas Institute Taderon Press. ISBN 978-0-9535191-7-0. LCCN 2005551875. OCLC 60664608.

- Der Yeghiayan, Zaven (2002). My Patriarchal Memoirs [Patriarkʻakan hushers]. Translated by Ared Misirliyan, copyedited by Vatche Ghazarian. Barrington, Rhode Island: Mayreni. ISBN 978-1-931834-05-6. LCCN 2002113804. OCLC 51967085.

Further reading

- Galustyan, R. (2013). "Հայ մտավորականության ոչնչացումը Հայոց ցեղասպանության ընթացքում (1915–1916 թթ.) [The Extermination of the Armenian Intelligentsia during the Armenian Genocide (1915–1916)]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). № 1 (1): 15–20.

External links

- Soghomon_Tehlirian,_Armenian_National_Hero!

- Media related to Deportation of Armenian notables in 1915 at Wikimedia Commons

- Armenian genocide

- Armenia-related lists

- Lists of Armenian people

- Lists of 20th-century people

- People who died in the Armenian genocide

- Armenians of the Ottoman Empire

- Political and cultural purges

- 1915 in the Ottoman Empire

- Deportation

- Ottoman Empire-related lists

- Persecution of Christians in the Ottoman Empire

- Persecution in the Ottoman Empire

- Persecution of intellectuals

- Anti-intellectualism

- 1910s-related lists

- April 1915 events