| Скенектади | |

|---|---|

Мемориальный зал Нотта, Юнион-колледж | |

| Девиз (ы): «Город, который освещает и уносит мир». | |

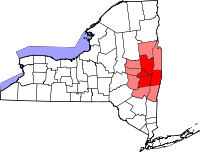

Расположение в округе Скенектади и штате Нью-Йорк . | |

Расположение в округе Скенектади и штате Нью-Йорк . | |

| Координаты: 42 ° 48′51 ″ N 73 ° 56′14 ″ з.д. / 42.81417°N 73.93722°W Координаты : 42 ° 48′51 ″ N 73 ° 56′14 ″ з.д. / 42.81417°N 73.93722°W | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| Состояние | Нью-Йорк |

| округ | Скенектади |

| Область, край | Столичный округ |

| Поселился | 1661 |

| Инкорпорированный | 1798 |

| Правительство | |

| • Мэр | Гэри Р. Маккарти |

| Область[1] | |

| • Город | 10,98 квадратных миль (28,43 км 2 ) |

| • Земля | 10,79 квадратных миль (27,95 км 2 ) |

| • Воды | 0,18 кв. Мили (0,48 км 2 ) |

| Население ( 2010 ) | |

| • Город | 66 135 |

| • Оценивать (2019) [2] | 65 273 |

| • Плотность | 6,048,28 / кв. Мили (2,335,22 / км 2 ) |

| • Метро | 1 170 483 |

| Часовой пояс | UTC − 5 ( восточное (EST) ) |

| • Лето ( DST ) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| индекс | 12301–12309, 12325, 12345 |

| Код (а) города | 518 |

| Код FIPS | 36-65508 |

| Идентификатор функции GNIS | 0964570 |

| Веб-сайт | www |

Schenectady ( / s к ə п ɛ к т ə г я / [3] [4] ) является город в Скенектади Каунти , Нью - Йорк , США, из которых оно округа. По данным переписи 2010 года , в городе проживало 66 135 человек, что делает его девятым по величине городом штата по численности населения. Название «Скенектади» происходит от слова могавков skahnéhtati , что означает «за соснами». [5] [6] Скенектади был основан на южной стороне реки Могавк.голландскими колонистами 17 века, многие из которых были из района Олбани . Голландцы передали название «Skahnéhtati», которое на самом деле является названием могавков для города Олбани, штат Нью-Йорк. Этим голландцам была запрещена торговля мехом из-за монополии Олбани, которая сохранила свой контроль после английского захвата в 1664 году. Жители новой деревни строили фермы на участках земли вдоль реки.

Соединенный с западом через реку Могавк и канал Эри , Скенектади быстро развивался в 19 веке как часть торгового, производственного и транспортного коридора в долине Ирокез. К 1824 году в обрабатывающей промышленности работало больше людей, чем в сельском хозяйстве или торговле, и в городе была хлопчатобумажная фабрика, перерабатывающая хлопок с Глубинного Юга . Многие фабрики в Нью-Йорке имели такие связи с Югом. В течение XIX века в Скенектади развивались влиятельные на национальном уровне компании и отрасли, в том числе General Electric и American Locomotive Company.(ALCO), которые были державами в середине 20 века. Schenectady был частью новых технологий, GE сотрудничала в производстве атомных подводных лодок, а в 21 веке работала над другими формами возобновляемой энергии.

Скенектади находится в восточной части Нью-Йорка , недалеко от слияния рек Могавк и Гудзон . Он находится в том же мегаполисе, что и столица штата Олбани , примерно в 24 км к юго-востоку. [7]

История [ править ]

Когда европейцы впервые встретили долину могавков, она была территорией нации ирокезов , одной из пяти наций Конфедерации ирокезов , или Haudenosaunee. Они занимали территорию в регионе по крайней мере с 1100 года нашей эры. С начала 1600 - х годов мохоки переместили свои поселения ближе к реке и 1629, они также захватили территории на западном берегу реки Гудзон , которые ранее были проведены в алгонкинских -speaking махиканами людей. [8]

В 1640-х годах у могавков было три крупных деревни, все на южном берегу реки Ирокез. Самым восточным был Оссерненон, расположенный примерно в 9 милях к западу от современного Орисвилля, штат Нью-Йорк . Когда голландские поселенцы построили форт Орандж (современный Олбани, Нью-Йорк ) в долине Гудзона в начале 1614 года, могавки назвали свое поселение skahnéhtati, что означает «за соснами», имея в виду большую площадь сосновых пустошей, лежащих между могавками. поселения и река Гудзон. Около 3200 акров этой уникальной экосистемы сейчас охраняются как Сосновый Буш Олбани . [9] Со временем это слово вошло в лексикон голландских поселенцев. Поселенцы в форте Оранж использовалиskahnéhtati для обозначения новой деревни на квартирах могавков (см. ниже), которая стала известна как Schenectady (с различными вариантами написания). [10] [11]

В 1661 году голландский иммигрант Арендт ван Корлаер (позже Ван Керлер) купил большой участок земли на южном берегу реки Могавк. Другим колонистам колониальное правительство предоставило земельные участки в этой части плоской плодородной речной долины, как части Новой Голландии . [ необходима цитата ] Поселенцы признали, что эти низменности веками возделывались ирокезами для выращивания кукурузы. [12]Ван Керлер взял самый большой участок земли; оставшаяся часть была разделена на участки по 50 акров для остальных первых четырнадцати собственников; Александр Линдси Глен, Филип Хендрикс Брауэр, Саймон Фолькерце Видер, Питер Адрианн Ван Воггллум, Теунис Корнелиз Сварт, Бастия Де Винтер, портрет Каталин Де Вос, Геррит Бэнкер, Уильям Теллер, Питер Якобс Борсбум, Питер Даниэль Ван Олинда (Ян Барент) ), Жак Корнелиз Ван Слик, Мартен Корнелиза Ван Эссельстин и Хармен Альберце Веддер. Поскольку большинство первых колонистов были из района Форт-Орандж, они, возможно, рассчитывали работать торговцами мехом, но Бевервейк(позже Олбани) торговцы сохранили монополию на законный контроль. Поселенцы здесь занялись земледелием. Их участки площадью 50 акров были уникальными для колонии, «разложенными полосами вдоль реки Могавк», с узкими краями, выходящими на реку, как во французском колониальном стиле. [13] Они полагались на выращивание домашнего скота и пшеницы. [13] Владельцы и их потомки контролировали всю землю города на протяжении поколений, [12] [13] по сути действуя как правительство до окончания Войны за независимость, когда было установлено представительное правительство.

С первых дней взаимодействия первые голландские торговцы в долине имели союзы с женщинами-могавками, если не всегда официальные браки. Их дети воспитывались в общине ирокезах, у которой была матрилинейная система родства , учитывая детей, рожденных в клане матери . Даже в обществе могавков биологические отцы играли второстепенные роли.

Некоторые потомки смешанной расы, такие как Жак Корнелиссен Ван Слик и его сестра Хиллети ван Олинда , которые имели голландские, французские и индейские корни, стали переводчиками и вступили в брак с голландскими колонистами. Они также получили землю в поселении Скенектади. [14] Они были одними из немногих метисов, которые, казалось, перешли из могавков в голландское общество, поскольку их называли «бывшими индейцами», хотя им не всегда было легко это сделать. [15] В 1661 году Жак унаследовал то, что стало известно как остров Ван Слика, от своего брата Мартена, которому его подарили могавки. Потомки семьи Ван Слик сохраняли собственность на протяжении 19 века. [16]

Из-за нехватки рабочей силы в колонии некоторые голландские поселенцы привезли в регион африканских рабов . В Скенектади они использовали их в качестве сельскохозяйственных рабочих. Англичане также импортировали рабов и продолжали заниматься сельским хозяйством в речной долине. Торговцы в Олбани сохранили контроль над торговлей мехом после поглощения англичанами.

В 1664 году англичане захватили голландскую колонию в Новых Нидерландах и переименовали ее в Нью-Йорк . Они подтвердили монополию Олбани на торговлю пушниной и издали приказы запретить Скенектади торговлю до 1670 года и позже. [17] Поселенцы приобрели дополнительную землю у могавков в 1670 и 1672 годах. (Жак и Хиллети Ван Слик получили участки земли по закону о могавках 1672 года для Скенектади.) [18] Двадцать лет спустя (1684 год) губернатор Томас Донган предоставил патент на письма. для Скенектади пять дополнительных попечителей. [19]

8 февраля 1690 года, во время войны короля Вильгельма , французские войска и их индийские союзники, в основном воины оджибве и алгонкины, неожиданно напали на Скенектади, в результате чего 62 человека погибли, 11 из них были африканскими рабами. [20] Американская история отмечает это как бойню в Скенектади . Всего в плен попали 27 человек, в том числе пять африканских рабов; рейдеры доставили своих пленников по суше примерно на 200 миль в Монреаль и связанную с ним миссионерскую деревню Канаваке . [20] Обычно молодые пленники усыновлялись семьями могавков, чтобы заменить умерших людей. [21]В начале 18 века в ходе набегов между Квебеком и северными британскими колониями некоторые пленные были выкуплены своими общинами. Колониальные правительства привлекались только для высокопоставленных офицеров или других чиновников. [21] В 1748 году, во время войны короля Георга , французы и индийцы снова напали на Скенектади, убив 70 жителей.

В 1765 году Скенектади был преобразован в городской округ. Во время войны за независимость США местное ополчение, 2-й полк ополчения округа Олбани , сражалось в битве при Саратоге и против войск лоялистов . Большая часть боевых действий в долине могавков происходила дальше на запад, на границе, в районах немецкого поселения Палатин к западу от Литл-Фоллс . Из-за их тесных деловых и других отношений с британцами некоторые поселенцы из города были лоялистами и переехали в Канаду на поздних этапах революции. Корона предоставила им землю в том, что стало известно как Верхняя Канада, а затем Онтарио.

Новая Республика [ править ]

Только после Войны за независимость жители деревни смогли ослабить власть потомков первых попечителей и получили представительное правительство. Поселение было зарегистрировано как город в 1798 году. Долгое время заинтересованные в поддержке высшего образования и нравственности, члены трех старейших церквей города - Первой голландской реформатской церкви, епископальной церкви Святого Георгия и Первой пресвитерианской церкви - образовали «союз». и основал Юнион-Колледж в 1795 году согласно грамоте штата. Школа началась в 1785 году как Академия Скенектади. Это основание было частью расширения высшего образования в северной части штата Нью-Йорк в послевоенные годы.

В этот период мигранты хлынули в северные и западные районы штата Нью-Йорк из Новой Англии, но были также новые иммигранты из Англии и Европы. Многие отправились на запад вдоль реки Могавк, обосновавшись в западной части штата, где они развили больше сельского хозяйства на бывших землях ирокезов. В центральной части штата развивалась молочная промышленность. Новые поселенцы были преимущественно английского и шотландско-ирландского происхождения. В 1819 году Скенектади пострадал от пожара, в результате которого было уничтожено более 170 зданий и большая часть его исторической самобытной архитектуры в голландском стиле. [22]

В Нью-Йорке был принят закон о постепенной отмене рабства в 1799 г. [23], но в 1824 г. в округе Скенектади все еще оставалось 102 раба, почти половина из которых проживала в городе. В том году в городе Скенектади проживало 3939 человек, в том числе 240 свободных чернокожих, 47 рабов и 91 иностранец. [24]

В 19 веке, после завершения строительства канала Эри в 1825 году, Скенектади стал важным транспортным, производственным и торговым центром. К 1824 году больше его населения работало в производстве, чем в сельском хозяйстве или торговле. [24] Среди отраслей промышленности была хлопчатобумажная фабрика, [24] которая перерабатывала хлопок из Глубинного Юга. Это был один из многих заводов в северной части штата, чья продукция была частью экспорта, вывозимого из Нью-Йорка. У города и штата было много экономических связей с югом, в то время как некоторые жители стали активными участниками движения за отмену смертной казни .

Скенектади выиграл от увеличения трафика, соединяющего реку Гудзон с долиной могавков и Великими озерами на западе и Нью-Йорком на юге. Олбани и Schenectady шлагбаум (теперь State Street) был построен в 1797 году для подключения к Олбани поселений в долине Mohawk. Mohawk и Хадсон железная дорога начали свою деятельность в 1831 году как один из первых железнодорожных линий в Соединенных Штатах, соединяющий город и Олбаните по маршруту через сосновые пустошимежду ними. Застройщики в Скенектади быстро основали Utica & Schenectady Railroad, зарегистрированную в 1833 году; Schenectady & Susquehanna Railroad, зафрахтована 5 мая 1836 г .; и Schenectady & Troy Railroad, зафрахтованная в 1836 году, что сделало Скенектади «железнодорожным узлом Америки в то время» и конкурировало с каналом Эри. [25] Товары из районов Великих озер и коммерческие товары отправлялись на восток и в Нью-Йорк через долину Могавк и Скенектади.

Последние рабы в Нью-Йорке и Скенектади получили свободу в 1827 году в соответствии с законом штата о постепенной отмене смертной казни. Закон сначала дал свободу детям, рожденным от матерей-рабынь, но они были переданы хозяину матери на срок до 20 лет. Юнион-колледж основал школу для чернокожих детей в 1805 году, но через два года закрыл ее. Некоторое время методисты помогали обучать детей, но государственные школы их не принимали. [26]

В 1830-х годах в Скенектади росло аболиционистское движение. В 1836 году преподобный Исаак Гроот Дурье (также известный как Дурье) стал соучредителем межрасового Общества борьбы с рабством в Юнион-колледже и Общества борьбы с рабством Скенектади в 1837 году. Искателей свободы поддерживал маршрут Подземной железной дороги, проходивший через область, переходящая на запад и север в Канаду, где было отменено рабство. [27]

В 1837 году Дурье вместе с другими свободными цветными людьми стал соучредителем Первой свободной церкви Скенектади (ныне Мемориальная церковь Дурье AME Zion). Он также основал школу для цветных студентов. Аболиционист Теодор С. Райт , афро-американский министр , базирующийся в Нью - Йорке, выступил на освящении церкви и похвалил школу. [26] [28]

В конце 19 века в долине могавков были созданы новые отрасли промышленности, работающие за счет реки. Рабочие места в промышленности привлекли много новых иммигрантов, сначала из Ирландии, а позже в этом веке из Италии и Польши. В 1887 году Томас Эдисон перевел свой машиностроительный завод Эдисона в Скенектади. В 1892 году Скенектади стал штаб-квартирой компании General Electric . Этот бизнес превратился в крупную промышленную и экономическую силу и помог сделать город и регион национальным производственным центром. [ необходима цитата ] GE стала важной на национальном уровне как креативная компания, расширяющаяся во многих различных областях. Американская Локомотивная Компанияздесь также развился из компании Schenectady и слил несколько небольших компаний в 1901 году; он был вторым в Соединенных Штатах по производству паровозов до разработки дизельной технологии.

20 век, чтобы представить [ править ]

Как и другие промышленные города в долине могавков, в начале 20 века Скенектади привлек много новых иммигрантов из восточной и южной Европы, поскольку они могли заполнить многие новые рабочие места в промышленности. Это также привлекло афроамериканцев в рамках Великой миграции из сельских районов Юга в северные города для работы. [29] General Electric и American Locomotive Company (ALCO) были промышленными центрами, оказавшими влияние на инновации в различных областях по всей стране.

Скенектади является домом для WGY , второй коммерческой радиостанции в Соединенных Штатах (после WBZ в Спрингфилде, штат Массачусетс , которая была названа в честь Вестингауза ). WGY была названа в честь ее владельца, General Electric (G), и города Скенектади. (Они). [30] В 1928 году General Electric произвела первые регулярные телевизионные передачи в Соединенных Штатах, когда экспериментальная станция W2XB начала регулярные передачи в четверг и пятницу после обеда. Эта телевизионная станция теперь называется WRGB ; в течение многих лет он был филиалом NBC Столичного округа , но с 1981 года был филиалом CBS .

Город достиг своего пика в 1930 году. Великая депрессия привела к потере рабочих мест и населения. В послевоенный период после Второй мировой войны некоторые жители переехали в новые дома в пригородах за городом . Кроме того, General Electric открыла несколько высокотехнологичных предприятий в соседнем городе Нискайуна., что способствовало продолжающемуся росту населения в округе. Во второй половине 20-го века Скенектади пострадал от масштабной промышленной и корпоративной реструктуризации, которая затронула большую часть США, в том числе железные дороги. Он потерял много рабочих мест и население в других местах, в том числе в оффшорах. С конца 20 века он формирует новую экономику, частично основанную на возобновляемых источниках энергии. Его население увеличилось с 2000 по 2010 год.

География [ править ]

По данным Бюро переписи населения США , город имеет общую площадь 11,0 квадратных миль (28,49 км 2 ), из которых 10,9 квадратных миль (28,23 км 2 ) - это земля и 0,1 квадратных мили (0,26 км 2 ) из них ( 1,27%) - вода.

Он является частью столичного округа , столичного района, окружающего Олбани , столицу штата Нью-Йорк. Наряду с Олбани и Троей , он является одним из трех основных населенных и промышленных центров региона.

Межгосударственная автомагистраль 890 проходит через Скенектади, а автомагистраль штата Нью-Йорк (межштатная автомагистраль 90) находится поблизости. У Amtrak есть станция в Скенектади. Ближайший аэропорт - аэропорт округа Скенектади ; ближайший коммерческий аэропорт - международный аэропорт Олбани .

Почтовый индекс Скенектади 12345 привлек внимание средств массовой информации своей простотой. [31]

Schenectady has a humid continental climate that is hot-summer (Dfa) bordering upon warm-summer (Dfb.) Average monthly temperatures range from 22.9 °F in January to 71.8 °F in July.[1]

Economy[edit]

Schenectady was a manufacturing center known as "The City that Lights and Hauls the World"—a reference to two prominent businesses in the city, the Edison Electric Company (now known as General Electric), and the American Locomotive Company (ALCO).

GE retains its steam turbine manufacturing facilities in Schenectady and its Global Research facility in nearby Niskayuna. Thousands of manufacturing jobs have been relocated from Schenectady to the Sun Belt and abroad. Corporate headquarters are now in Boston.[32]

ALCO produced steam locomotives for railroads for years. Later it became renowned for its "Superpower" line of high-pressure locomotives, such as those for the Union Pacific Railroad in the 1930s and 1940s. During World War II, it converted to support the war, making tanks for the US Army. As diesel locomotives began to be manufactured, ALCO joined with GE to develop diesel locomotives to compete with GM's EMD division. But corporate restructuring to cope with the changing locomotive procurement environment led to ALCO's slow downward spiral. Its operations fizzled as it went through acquisitions and restructuring in the late 1960s. Its Schenectady plant closed in 1969.

In the late 20th century, due to industrial restructuring, the city lost many jobs and suffered difficult financial times, as did many former manufacturing cities in upstate New York. The loss of employment caused Schenectady's population to decline by nearly one-third from 1950 into the late 20th century. The early industries had left many sites contaminated with hazardous wastes. Such environmental brownfields have needed technical approaches for redevelopment.

In the 21st century, Schenectady began revitalization. GE established a renewable energy center that brought hundreds of employees to the area. The city is part of a metropolitan area with improving economic health, and a number of buildings have been renovated for new uses. Numerous small businesses, retail stores and restaurants have developed on State Street downtown.[33]

Price Chopper Supermarkets and the New York Lottery are based in Schenectady.

In December 2014, the state announced that the city was one of three sites selected for development of off-reservation casino gambling, under terms of a 2013 state constitutional amendment. The project would redevelop an ALCO brownfield site in the city along the waterfront, with hotels, housing and a marina in addition to the casino.[34]

In February 2017, the Rivers Casino & Resort opened with 66 table games and 1,150 slot machines on a 50,000-square-foot gambling floor with a steakhouse and a restaurant lounge.[35] The $480 million residential-retail project on 60 acres includes a marina, two hotels, condos, apartments and retail and office space for tech firms.[35]

Demographics[edit]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 5,289 | — | |

| 1810 | 5,903 | 11.6% | |

| 1820 | 3,939 | −33.3% | |

| 1830 | 4,268 | 8.4% | |

| 1840 | 6,784 | 59.0% | |

| 1850 | 8,921 | 31.5% | |

| 1860 | 9,579 | 7.4% | |

| 1870 | 11,026 | 15.1% | |

| 1880 | 13,655 | 23.8% | |

| 1890 | 19,902 | 45.7% | |

| 1900 | 31,682 | 59.2% | |

| 1910 | 72,826 | 129.9% | |

| 1920 | 88,723 | 21.8% | |

| 1930 | 95,692 | 7.9% | |

| 1940 | 87,549 | −8.5% | |

| 1950 | 91,785 | 4.8% | |

| 1960 | 81,070 | −11.7% | |

| 1970 | 77,958 | −3.8% | |

| 1980 | 67,972 | −12.8% | |

| 1990 | 65,566 | −3.5% | |

| 2000 | 61,821 | −5.7% | |

| 2010 | 66,135 | 7.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 65,273 | [2] | −1.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[36] | |||

In the census of 2010, there were 66,135 people, 26,265 (2000 data) households, and 14,051 (2000 data) families residing in the city. The population density was 6,096.7 people per square mile (2,199.9/km2). There were 30,272 (2000 data) housing units at an average density of 2,790.6 per square mile (1,077.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 59.38% (52.31% Non-Hispanic) (7.07 White-Hispanic) White, 24.19% African American, 14.47% Hispanic or Latin of any race, 8.24% from other races, 5.74% from two or more races, 2.62% Asian American, 0.69% Native American, and 0.14% Pacific Islander. There is a growing Guyanese population in the area. The top ancestries self-identified by people on the census are Italian (13.6%), Guyanese (12.3%), Irish (12.1%), Puerto Rican (10.1%), German (8.7%), English (6.0%), Polish (5.4%), French (4.4%). These reflect historic and early 20th-century immigration, as well as that since the late 20th century.[37]

The Schenectady City School District is very diverse; (71%- 2011)(80%–2013) of district students receive free or reduced lunch. The student population of the school district is majority minority: 35% Black (48% Graduate), 32% White (71% Graduate), 18% Hispanic (51% Graduate), 15% Asian (68% Graduate). As of 2016, the graduation rate for the high school was 56%.[38]

Using 2010 data, there were 28,264 households, out of which 31.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28.0% were married couples living together, 24.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.5% were non-families. 38.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the city, the year 2010 population was spread out, with 26.3% under the age of 18, 13.6% from 18 to 24, 30.7% from 25 to 44, 21.1% from 45 to 64, and 7.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32. For every 100 females, there were 92.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city in 2000 was $29,378 (2010–$37,436), and the median income for a family was $41,158. Males had a median income of $32,929 versus $26,856 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,076. About 20.2% of families and 25.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.5% of those under age 18 and 5.6% of those age 65 or over.

Religion[edit]

The largest religious body is the Catholic church, with 44,000 adherents, followed by Islam, with 6,000 followers. The third largest religious body is the Reformed Church in America, with 3,600 members. The fourth is the United Methodist denomination, with 2,800 members.[39]

Notable congregations are the First Presbyterian Church (Schenectady, New York), which is affiliated with the PCA. First Reformed Church RCA is formed in the 17th century, one of the oldest churches in the town. St George's Episcopal Church dates back to 1735; it shared facilities with the Presbyterians for more than 30 years.[40]

Rail transportation[edit]

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides regular service to Schenectady, with Schenectady station at 322 Erie Boulevard. Trains include the Ethan Allen, Adirondack, Lake Shore Limited, Maple Leaf, and Empire Service. Schenectady also has freight rail service from Canadian Pacific Railway and Norfolk Southern Railway.

In the early 20th century, Schenectady had an extensive streetcar system that provided both local and interurban passenger service. The Schenectady Railway Co. had local lines and interurban lines serving Albany, Ballston Spa, Saratoga Springs and Troy. There was also a line from Gloversville, Johnstown, Amsterdam, and Scotia into Downtown Schenectady operated by the Fonda, Johnstown, and Gloversville Railroad. The nearly 200 leather and glove companies in the Gloversville region generated considerable traffic for the line. Sales representatives carrying product sample cases began their sales campaigns throughout the rest of the country by taking the interurban to reach Schenectady's New York Central Railroad station, where they connected to trains to New York City, Chicago and points between.

The bright orange FJ&G interurbans were scheduled to meet every daylight New York Central train that stopped at Schenectady. Through the 1900s and into the early 1930s, the line was quite prosperous. In 1932 the FJ&G purchased five lightweight "bullet cars" (#125 through 129) from the J. G. Brill Company. These interurbans represented state-of-the-art design: the "bullet" description referred to the unusual front roof that was designed to slope down to the windshield in an aerodynamically sleek way. FJ&G bought the cars believing that there would be continuing strong passenger business from a prosperous glove and leather industry, as well as legacy tourism traffic to Lake Sacandaga north of Gloversville. Instead, roads were improved, automobiles became cheaper and were purchased more widely, tourists traveled greater distances by car, and the Great Depression decreased business overall.

FJ&G ridership continued to decline and in 1938 New York state condemned the line's bridge over the Mohawk River at Schenectady. The bridge had once carried cars, pedestrians, and the interurban, but ice flow damage in 1928 prompted the state to restrict its use to the interurban. When the state condemned the bridge for interurban use, the line abandoned passenger service, and the bullet cars were sold. Freight business had also been important to the FJ&G, and it continued over the risky bridge into Schenectady a few more years.

Places of interest[edit]

- Proctors Theatre is an arts center. Built in 1926 as a vaudeville/movie theater, it has been refurbished in the 21st century. It is home to "Goldie," a Wurlitzer theater pipe organ. Proctor's was also the site of one of the first public demonstrations of television, projecting an image from a studio at the GE plant a mile [1.6 km] away. Its 2007 renovation added two theatres: Proctors is home to three theaters, including the historic Mainstage, the GE Theatre, and 440 Upstairs.

- The Stockade Historic District features dozens of Dutch and English Colonial houses from the 18th and 19th centuries. It is New York state's first historic district, designated in 1965 by the Department of Interior and named after the historic stockade that originally surrounded the colonial settlement.[41]

- The Schenectady County Historical Society has a History Museum and the Grems-Doolittle research library, both at 32 Washington Avenue in the Stockade District. It has adapted a house originally built in 1895 for the Jackson family. It was used by the GE Women's Club from 1915 until 1957, when it was donated to the Historical Society. The History Museum tells of the history of Schenectady, the Yates Doll House, the Erie Canal, the Glen-Sanders Collection, etc. The research library has many collections of papers, photographs, and books. It welcomes people doing local and genealogical research.

- The General Electric Realty Plot, near Union College, was one of the first planned residential neighborhoods in the U.S. and designed to attract GE executives in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It features an eclectic collection of grand homes in a variety of architectural styles, including Tudor, Dutch Colonial, Queen Anne, and Spanish Colonial. The Plot is home to the first all-electric home in the United States. It hosts an annual House and Garden Tour.

- Union College, adjacent to the GE Realty Plot, is the oldest planned college campus in the United States. The campus features the unique 16-sided Nott Memorial building, built in 1875, and Jackson's Garden, eight acres (32,000 m2) of formal gardens and woodlands.

- Central Park is the crown jewel of Schenectady's parks. It occupies the highest elevation point in the city. The Common Council voted in 1913 to purchase the land for the present site of the park. The park features an acclaimed rose garden and Iroquois Lake. Its stadium tennis court was the former home to the New York Buzz of the World Team Tennis league (as of 2008). Central Park was named after New York City's Central Park.[citation needed]

- The Schenectady Museum features exhibits on the development of science and technology. It contains the Suits-Bueche Planetarium.

- Schenectady City Hall is the focal point of city government. Designed by McKim, Mead and White, it was built in 1933 during the Great Depression.

- Schenectady's Municipal Golf Course is an 18-hole championship facility sited among oaks and pines. Designed in 1935 by Jim Thompson under the WPA, the course was ranked by Golf Digest among "Best Places to Play in 2004" and received a three-star rating.

- Jay Street, between Proctor's and City Hall, is a short street partially closed to motor traffic. It features a number of small, independently operated businesses and eateries and is a popular destination. Just past the pedestrian section of Jay Street is Schenectady's Little Italy on North Jay Street.

- Schenectady Light Opera Company (SLOC) is a community theater group on Franklin Street in downtown Schenectady.

- The Edison Tech Center exhibits and promotes the physical development of engineering and technology from Schenectady and elsewhere. It provides online and on-site displays that promote learning about electricity and its applications in technology.[42]

- Upper Union Street Business Improvement District, near the Niskayuna boundary, is home to almost 100 independently owned businesses, including a score of restaurants, upscale retail, specialty shops, salons and services.

- Vale Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, includes more than 30,000 burials of noted and ordinary residents of the city. It includes the historic African-American Burying Ground, where city residents annually celebrate anniversaries of Juneteenth and Emancipation.

Education[edit]

The city is served by the Schenectady City School District, which operates 16 elementary schools, three middle schools and the main high school Schenectady High School. Brown School is a private, nonsectarian kindergarten-through-8th grade school. Catholic schools are administered by the Diocese of Albany.

Wildwood School is a special education, all-ages school.[43]

Schenectady's tertiary educational institutions are Union College, a private liberal arts college, and Schenectady County Community College, a public community college.[44][45]

Representation in popular culture[edit]

Due to its early importance in national history and the economy, Schenectady figured in popular culture.

Fiction[edit]

- Author Henry James gave his lead character Daisy Miller, in his 1878 novella of the same name, an origin in Schenectady.

- Schenectady is referred to or the setting for several of Kurt Vonnegut's books, most notably Hocus Pocus and Player Piano.

- Doctor Octopus, a Marvel Comics supervillain, was born in Schenectady.

- Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.'s Lovecraftian serial killer novel, Nightmare's Disciple (Chaosium, 1999) is set in Schenectady.

- Science fiction writer Harlan Ellison said that anytime a fan or interviewer asked him "Where do you get your ideas?", he would reply "Schenectady".[46] Science fiction writer Barry Longyear subsequently titled a collection of his short stories It Came From Schenectady.[47]

Film and TV[edit]

- In Objective, Burma! (1945), Sid Jacobs (William Prince) tells Mark Williams (Henry Hull) about his house on Crane Street in Schenectady. He had taught at Pleasant Valley school before the war.

- In the 1950s television series, The Honeymooners, Trixie's mother was from Schenectady.

- The Way We Were (1973) was filmed on location at Union College, and in nearby Ballston Spa.

- The 1980s film Heart Like a Wheel is mostly set in Schenectady.

- The 1996 made-for-TV film Unabomber: The True Story starring Robert Hays as David Kaczynski, brother of unabomber Ted Kaczynski, refers to Schenectady, where David and his wife were living when they figured out his brother's involvement in the bombings.

- Star Trek: Enterprise (2001), Starfleet Captain Jonathan Archer is born in Schenectady in 2112.

- The Time Machine (2002), the remake starring Guy Pearce, features Schenectady's Central Park in the ice skating scenes, standing in for New York City's Central Park.

- Synecdoche, New York (2008) is a film partially set in Schenectady, where some scenes were shot. It plays on the aural similarity between the city's name and the figure of speech synecdoche.

- In the ABC-TV series Ugly Betty, Marc St. James (played by Michael Urie) is said to be from Schenectady.

- Winter of Frozen Dreams (2009) was entirely filmed in Schenectady County, but is set in Wisconsin, where the historic events took place. It features the Schenectady, the Town of Rotterdam, and the Village of Scotia, all in New York. The film stars Thora Birch as Barbara Hoffman, the historic Wisconsin murderer, and Keith Carradine as a detective determined to catch her.

- The Place Beyond the Pines (2013), starring Bradley Cooper and Ryan Gosling, was filmed locally in 2011 near the Schenectady Police Headquarters and other areas of Schenectady.

- In the NBC sitcom Will & Grace, Schenectady is the hometown of character Grace Adler (played by Debra Messing).

Music[edit]

- The music video for the song "Hero" by Mariah Carey was filmed at Proctors Theatre in Schenectady.[48]

- The song "Someone to Love" by Fountains of Wayne, refers to fictional character Seth Shapiro moving from Schenectady in 1993 to Brooklyn.

- The song "Join the Circus", the last major number in Cy Coleman's musical Barnum, mentions the city in its lyric.

Notable people[edit]

- Stephen Alexander (1806–1883), astronomer, mathematician, and educator[49]

- Horatio Allen (1802–1889), railroad engineer and inventor[49]

- Ralph Alpher (1921–2007), cosmologist, won National Medal of Science for seminal work on Big Bang Theory

- Chester Arthur (1829–1886), U.S. president, lived in Schenectady while attending Union College

- Kumar Barve (born 1958), Majority Leader and first Indian-American legislator in the Maryland House of Delegates

- Suzanne Basso, murderer

- Andy Bloom (born 1973), Olympic shotputter

- Jim Barbieri (born 1941), MLB outfielder who played for Schenectady's 1954 Little League World Series championship team

- Maria Brink (born 1977), lead singer of band In This Moment, was born in Schenectady

- Pat Cadigan (born 1953), science fiction author, was born in Schenectady

- Greg Capullo (born 1962), comic book artist, was born in Schenectady

- Bruce W. Carter (1950-1969), USMC, Medal of Honor Recipient, was born in Schenectady

- Jimmy Carter (born 1924), U.S. president, studied briefly at Union College

- Billy Connors (1941–2018), MLB pitcher, coach and executive who played for Schenectady's 1954 Little League World Series championship team

- Jackie Craven, architectural writer

- Dexter Curtis (1828–1898), Wisconsin State Assemblyman, was born in Schenectady[50]

- Mary Daly (1928–2010), feminist theologian

- Ann B. Davis (1926–2014), actress (Schultzy on The Bob Cummings Show and Alice Nelson on The Brady Bunch), was born in Schenectady

- Antonio Delgado (born 1977), U.S. representative

- Amir Derakh (born 1963), guitarist for rock band Orgy, was born in Schenectady

- Paul "Legs" DiCocco (1924–1989), gambler and racketeer

- John Owen Dominis (1832–1891), prince consort of Queen Liliuokalani of Hawaii

- Jamie Dukes (born 1964), football player, born in Schenectady

- Harry J. Flynn (1933–2019), Roman Catholic archbishop of Minneapolis and St. Paul, was born in Schenectady

- Henry Glen (1739–1814), Continental army officer, U.S. representative

- Harold Gould (1923–2010), actor (The Golden Girls, The Sting), was born in Schenectady

- Harold J. Greene (1959–2014), United States Army general[51]

- Kevin Greene (1962-2020), football linebacker, coach

- Joseph E. Grosberg (1883–1970), pioneer in supermarket and wholesale foods industries

- John E. Hart (1824–1863), Union Navy officer

- Keith Hitchins (1931–2020), American historian

- Gilbert Hyatt (ca. 1761–1823), loyalist, founder of Sherbrooke, Quebec

- Fred Isabella (1917–2007), dentist, businessman, and politician

- Patricia Kalember (born 1957), actress, born in Schenectady

- Steve Katz (born 1945), guitarist (Blood, Sweat & Tears)

- Barry Kramer (born 1942), basketball player, jurist

- Irving Langmuir (1881–1957), 1932 Nobel laureate in chemistry

- Wayne LaPierre (born 1949), CEO of the NRA

- Arnold Lobel (1933–1987), author and illustrator of children's books, was born in Los Angeles and raised in Schenectady

- George R. Lunn, (1873–1948), mayor, U.S. representative, lieutenant governor

- Ranald MacDougall (1915–1973), screenwriter and director

- Sir Charles Mackerras (1925–2010), Australian conductor, was born in Schenectady.

- John Van Antwerp MacMurray (1881–1960), U.S. China expert

- Donald Martiny (born 1953), artist

- Tom Moulton (born 1940), record producer

- Shirley Muldowney (born 1940), auto racer in International Motorsports Hall of Fame, born and raised in Schenectady

- Ray Nelson (born 1931), science-fiction author and cartoonist, born in Schenectady

- Sterling Newberry, inventor, worked at General Electric in Schenectady

- Eliphalet Nott (1773–1866), president of Union College

- Jean-Hervé Peron (born 1949), Germany rock musician, lived in Schenectady in 1967–1968 as exchange student

- Jacob Van Vechten Platto (1822–1898), Wisconsin state assemblyman

- Joseph S. Pulver (1955-2020), novelist, poet, editor, born in Schenectady

- Pat Riley (born 1945), NBA player, executive and Hall of Fame coach, was born in Rome, NY, lived in Schenectady

- Don Rittner, author and historian, lived in Schenectady

- Ron Rivest (born 1947), cryptographer, co-inventor of RSA cryptography

- Lewis K. Rockefeller (1875–1948), U.S. representative, born in Schenectady

- Al Romano (born 1954), football player

- Margaret Rotundo (born 1949), Maine legislator

- Mickey Rourke (born 1952), Academy Award-nominated actor, born in Schenectady

- R. Tom Sawyer (1901–1986), engineer, writer and inventor of the first successful gas turbine locomotive, born in Schenectady[52]

- John Sayles (born 1950), film director and Academy Award-nominated screenwriter, born and raised in Schenectady

- Vincent J. Schaefer (1906–1993), chemist, meteorologist

- Amalie Schoppe (1791–1858), German writer

- Michael H. Schill (born 1958), president of the University of Oregon

- Ben Schwartz (born 1981), actor, (Jean-Ralphio Saperstein on Parks and Recreation), graduated from Union College in 2003

- William H. Seward (1801–1872), Abolitionist Republican Governor of New York, U.S. Senator, U.S. Secretary of State during and after the Civil War

- Nehemiah Shumway (1761–1843), teacher and musical composer, lived in Schenectady

- Kenneth Schermerhorn (1929–2005), conductor of Nashville Symphony, born in Schenectady

- Simon J. Schermerhorn (1827–1901), U.S. Representative

- Gerald Stano (1951–1998), serial killer

- Charles Proteus Steinmetz (1865–1923), mathematician, electrical engineer, developer of alternating current[53]

- Brian U. Stratton (born 1957), mayor, director of the New York State Canal Corporation

- Samuel S. Stratton (1916–1990), mayor, U.S. representative, father of Brian Stratton

- Frank Taberski (1889–1941), billiards champion; born in Schenectady

- Lynne Talley (born 1954), oceanographer, born in Schenectady

- Marybeth Tinning (born 1942), serial killer

- John Tudor (born 1954), MLB pitcher

- Deborah Van Valkenburgh (born 1952), actress (The Warriors), was born in Schenectady

- Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007), author, lived in Schenectady while working for GE in the early 1950s

- Lee Wallard (1910–1963), race car driver

- George H. Wells (1833–1905), Confederate officer, attorney and member of the Louisiana State Senate

- Casper Wells (born 1984), MLB outfielder

- George Westinghouse (1846–1914), engineer and inventor, grew up in Schenectady[53]

- Andrew Yang (born 1975), entrepreneur, 2020 Democratic presidential candidate, 2021 New York City mayor candidate

- Charles Yates (1808–1870), Union Army brigadier general during the American Civil War; nephew of Joseph Christopher Yates

- Joseph Christopher Yates (1768–1837), governor of New York

- Clifton Young (1917–1951), actor

Sister city[edit]

Nijkerk, Netherlands

Nijkerk, Netherlands

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Schenectady". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Schenectady". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ^ "Google Arts, Schenectady". Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Mohawk Frontier, Second Edition: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661-1710. Suny Press. 5 February 2009. ISBN 9781438427072. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Mileage Map", NY Department of Transportation

- ^ Burke Jr, T. E., & Starna, W. A. (1991). Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661–1710, SUNY Press. p. 26

- ^ Mithun, Marianne (1999), The Languages of Native North America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. viii, ISBN 978-0-521-23228-9, OCLC 40467402

- ^ Pearson, Jonathan (1883). J.W. MacMurray (ed.). A History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times. J. Munsells, Sons.

- ^ Lorna Czarnota. 2008.Native American & Pioneer Sites of Upstate New York: Westward Trails from Albany to Buffalo. The History Press, p. 23

- ^ a b Prof. John Pearson, "Chap 6: Division of Lands", A History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times (1883), Schenectady Digital History Archive

- ^ a b c Robert V. Wells, "Review: 'Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661–1710' by Thomas E. Burke, Jr.", The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 1, Law and Society in Early America (Jan., 1993), pp. 214–216(subscription required)

- ^ Burke Jr, T. E., & Starna, W. A. (1991). Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661–1710. SUNY Press, p. 93

- ^ Midtrød, Tom Arne. "The Flemish Bastard and the Former Indians: Métis and Identity in Seventeenth-Century New York", The American Indian Quarterly, Volume 34 (Winter 2010): 86. Project Muse

- ^ George Rogers Howells and John Munsell, History of the County of Schenectady, 1662–1886, New York: W.W. Munsell & Co., 1886, pp. 14–15

- ^ Burke (1991), Mohawk Frontier, p. 116

- ^ Burke (1991), Mohawk Frontier, p. 183

- ^ Robert G. Sullivan, Schenectady County Public Library. "A History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times 5: Introduction". schenectadyhistory.org. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b Jonathan Pearson, Chap. 9, "Burning of Schenectady", History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times, 1883, pp. 244–270

- ^ a b John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America, ISBN 978-0679759614

- ^ Prof. John Pearson, "Preface", p. xii, History of the Schenectady Patent in the Dutch and English Times (1883), Library of Congress, full scanned text at Internet Archive

- ^ Douglas Harper, "Emancipation in New York", Slavery in the North, 2003, accessed 1 January 2015

- ^ a b c Horatio Gates Spafford, LL.D. A Gazetteer of the State of New-York, Embracing an Ample Survey and Description of Its Counties, Towns, Cities, Villages, Canals, Mountains, Lakes, Rivers, Creeks and Natural Topography. Arranged in One Series, Alphabetically: With an Appendix… (1824), at Schenectady Digital History Archives, selected extracts, accessed 28 December 2014

- ^ Don Rittner, "American Railroading Began Here", Schenectady county and city history, accessed 3 January 2015

- ^ a b Theodore Sedgwick Wright, "Speech given during the dedication of the First Free Church of Schenectady, 28 December 1837", Emancipator, at University of Detroit Mercy, accessed 31 May 2012

- ^ "Underground Railroad and Anti-Slavery Movement in Schenectady", Schenectady Historical Society, July 2010

- ^ Neisuler, J. G. (1964). The History of Education in Schenectady, 1661–1962, Schenectady: Board of Education, City School District

- ^ Gregory, James N. (2009) "The Second Great Migration: An Historical Overview," African American Urban History: The Dynamics of Race, Class and Gender since World War II, eds. Joe W. Trotter Jr. and Kenneth L. Kusmer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 22.

- ^ Brian Belanger,Radio & Television Museum News, "Radio Station WGY", Radio History, February 2006. Retrieved on December 1, 2008 Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "12345: The Easiest ZIP Code in the Country, Toughest to Sort Mail in Schenectady". Spectrum News. 18 September 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Egan, Matt. "Even GE's Boston headquarters is shrinking". cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa W. (February 28, 2010). "Union College Finally Admits Where It Is". The New York Times.

- ^ Rick Karlin, Kenneth C. Crowe II and Paul Nelson, "Fortune smiles on Schenectady casino proposal", Times Union, 18 December 2014, accessed 18 December 2014

- ^ a b Nelson, Paul. Rivers Casino & Resort opens in Schenectady Times Union. 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "State high school graduation rates rise". Times Union. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- ^ "ARDA stats".

- ^ "St george' Episcopal Church history page".

- ^ Scheltema, Gajus and Westerhuijs, Heleen (eds.),Exploring Historic Dutch New York, New York: Museum of the City of New York/Dover Publications, (2011) ISBN 978-0-486-48637-6

- ^ "Edison Tech Center". edisontechcenter.org. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Day/Residential Schools – Eastern Region: Special Education : EMSC : NYSED". nysed.gov. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Lisa W. Foderaro (February 28, 2010). "Union College Finally Admits Where It Is". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ Shawn G. Kennedy (October 18, 1987). "The Clouds Burn Off in Schenectady". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

...the city's two major educational institutions, Schenectady County Community College and Union College.

- ^ Interview with Harlan Ellison Archived 2012-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, Doorly

- ^ "It Came From Schenectady", Science Fiction Fans

- ^ "Proctors Theatre Near Albany, NY". albany.com. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ a b Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Marquis Who's Who. 1967.

- ^ 'Wisconsin Blue Book 1883, Biographical Sketch of Dexter Curtis, pg. 487

- ^ Air Force Mortuary Affairs (August 7, 2014). "Army Maj. Gen. Harold J. Greene honored in dignified transfer Aug. 7". United States Air Force. United States Department of the Air Force. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ ASME News (Vol.5, No. 9, March 1986)

- ^ a b "Great Inventors of New York's Capital District".

Further reading[edit]

- The Fonda, Johnstown, and Gloversville RR: The Sacandaga Route to the Adirondacks. Randy Decker, Arcadia Publishing.

- Our Railroad: The Fonda, Johnstown, and Gloversville RR 1867 to 1893. Paul Larner, St. Albans, VT.

- The Steam Locomotive in America. Alfred W. Bruce, 1952, Bonanza Books division of Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, NY.

- Morse, J. (1797). "Skenectady". The American Gazetteer. Boston, Massachusetts: S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews. OL 23272543M.

- Yates, Austin A. Schenectady County, New York: Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century, New York: New York History Company, 1902, full scanned text online at Allen Public Library, at Internet Archive.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schenectady, New York. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Schenectady. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Schenectady. |

- City of Schenectady (official website)

- Schenectady County Chamber of Commerce