Ostracod

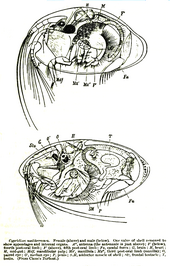

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified,[1] grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typically around 1 mm (0.039 in) in size, but varying from 0.2 to 30 mm (0.008 to 1.181 in) in the case of Gigantocypris. Their bodies are flattened from side to side and protected by a bivalve-like, chitinous or calcareous valve or "shell". The hinge of the two valves is in the upper (dorsal) region of the body. Ostracods are grouped together based on gross morphology. While early work indicated the group may not be monophyletic;[2] and early molecular phylogeny was ambiguous on this front,[3] recent combined analyses of molecular and morphological data found support for monophyly in analyses with broadest taxon sampling.[4]

Ecologically, marine ostracods can be part of the zooplankton or (most commonly) are part of the benthos, living on or inside the upper layer of the sea floor. Many ostracods, especially the Podocopida, are also found in fresh water, and terrestrial species of Mesocypris are known from humid forest soils of South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[5] They have a wide range of diets, and the group includes carnivores, herbivores, scavengers and filter feeders.

As of 2008, around 2000 species and 200 genera of nonmarine ostracods are found.[6] However, a large portion of diversity is still undescribed, indicated by undocumented diversity hotspots of temporary habitats in Africa and Australia.[7] Of the known specific and generic diversity of nonmarine ostracods, half (1000 species, 100 genera) belongs to one family (of 13 families), Cyprididae.[7] Many Cyprididae occur in temporary water bodies and have drought-resistant eggs, mixed/parthenogenetic reproduction, and the ability to swim. These biological attributes preadapt them to form successful radiations in these habitats.[8]

Ostracods are "by far the most common arthropods in the fossil record"[9] with fossils being found from the early Ordovician to the present. An outline microfaunal zonal scheme based on both Foraminifera and Ostracoda was compiled by M. B. Hart.[10] Freshwater ostracods have even been found in Baltic amber of Eocene age, having presumably been washed onto trees during floods.[11]

Ostracods have been particularly useful for the biozonation of marine strata on a local or regional scale, and they are invaluable indicators of paleoenvironments because of their widespread occurrence, small size, easily preservable, generally moulted, calcified bivalve carapaces; the valves are a commonly found microfossil.

A find in Queensland, Australia in 2013, announced in May 2014, at the Bicentennary Site in the Riversleigh World Heritage area, revealed both male and female specimens with very well preserved soft tissue. This set the Guinness World Record for the oldest penis.[12] Males had observable sperm that is the oldest yet seen and, when analysed, showed internal structures and has been assessed as being the largest sperm (per body size) of any animal recorded. It was assessed that the fossilisation was achieved within several days, due to phosphorus in the bat droppings of the cave where the ostracods were living.[13]