| Вен | |

|---|---|

Основные вены в теле человека | |

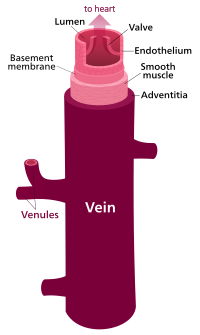

Структура жилы, состоящая из трех основных слоев. Внешний слой представляет собой соединительную ткань , называемую адвентициальной оболочкой или внешней оболочкой ; средний слой гладкой мускулатуры, называемый оболочкой среды , и внутренний слой, выстланный эндотелиальными клетками, называемый внутренней оболочкой . | |

| Подробности | |

| Система | Сердечно-сосудистая система |

| Идентификаторы | |

| латинский | вена |

| MeSH | D014680 |

| TA98 | А12.0.00.030 А12.3.00.001 |

| TA2 | 3904 |

| FMA | 50723 |

| Анатомическая терминология | |

Вены - это кровеносные сосуды, по которым кровь движется к сердцу . Большинство вен несут дезоксигенированную кровь от тканей обратно к сердцу; Исключение составляют легочные и пупочные вены , по которым насыщенная кислородом кровь переносится к сердцу. В отличие от вен, артерии несут кровь от сердца.

Вены менее мускулистые, чем артерии, и часто расположены ближе к коже. В большинстве вен есть клапаны, предотвращающие обратный ток .

Структура [ править ]

Вены расположены по всему телу в виде трубок, по которым кровь возвращается к сердцу. Вены классифицируются по разным причинам: поверхностные и глубокие, легочные и системные, большие и маленькие.

- Поверхностные вены - это те, которые расположены ближе к поверхности тела и не имеют соответствующих артерий.

- Глубокие вены расположены глубже в теле и имеют соответствующие артерии.

- Перфораторные вены стекают от поверхностных к глубоким венам. [1] Обычно это касается нижних конечностей и стоп.

- Сообщающиеся вены - это вены, которые напрямую соединяют поверхностные вены с глубокими венами.

- Легочные вены - это набор вен, по которым насыщенная кислородом кровь от легких доставляется к сердцу.

- Системные вены дренируют ткани тела и доставляют дезоксигенированную кровь к сердцу.

Большинство вен оборудовано односторонними клапанами , похожими на клапан утконоса , чтобы предотвратить кровоток в обратном направлении.

Вены полупрозрачные, поэтому цвет вены снаружи организма во многом определяется цветом венозной крови , которая обычно темно-красная из-за низкого содержания в ней кислорода. Вены кажутся синими из-за низкого уровня кислорода в венах. На цвет вены могут влиять характеристики кожи человека, количество кислорода, переносимого кровью, а также размер и глубина сосудов. [2] Когда из вены сливают кровь и удаляют из организма, она становится серо-белой. [ необходима цитата ]

Венозная система [ править ]

Самые большие вены в человеческом теле - полые вены . Это две большие вены, которые входят в правое предсердие сердца сверху и снизу. Верхней полой вены несет кровь от рук и головы в правое предсердие сердца, в то время как нижняя полая вена несет кровь от ног и живота к сердцу. Нижняя полая вена является забрюшинным и проходит вправо примерно параллельно брюшной аорте вдоль позвоночника . Большие вены впадают в эти две вены, а более мелкие - в эти. Вместе это формирует венозную систему.

В то время как основные вены занимают относительно постоянное положение, положение вен от человека к человеку может сильно варьироваться. [3]

В легочных венах несут относительно кислорода крови из легких в сердце. В улучшенных и низших полых вен несут относительно венозная кровь из верхней и нижней части системных тиражами, соответственно.

Система воротной вены - это серия вен или венул, которые напрямую соединяют два капиллярных русла . Примеры таких систем включают печеночную воротную вену и гипофизарную портальную систему .

По периферическим венам течет кровь конечностей, кистей и стоп .

Микроанатомия [ править ]

Микроскопически вены имеют толстый внешний слой, состоящий из соединительной ткани , который называется наружной оболочкой или адвентициальной оболочкой . Во время процедур, требующих венозного доступа, таких как венопункция , можно заметить легкий «хлопок», когда игла проникает в этот слой. Средний слой полос гладкой мускулатуры называется средой оболочкой и, как правило, намного тоньше, чем у артерий, поскольку вены не функционируют в основном сократительным образом и не подвергаются высокому систолическому давлению, в отличие от артерий. Внутренняя часть выстлана эндотелиальными клетками, которые называются внутренней оболочкой.. Точное расположение вен гораздо больше варьируется от человека к человеку, чем расположение артерий . [4]

Функция [ править ]

Вены служат для возврата крови от органов к сердцу. Вены также называют «емкостными сосудами», потому что большая часть объема крови (60%) содержится в венах. В большом круге кровообращения насыщенная кислородом кровь перекачивается левым желудочком по артериям к мышцам и органам тела, где ее питательные вещества и газы обмениваются в капиллярах . После поглощения клеточных отходов и углекислого газа капиллярами кровь направляется через сосуды, которые сходятся друг с другом, образуя венулы, которые продолжают сходиться и формировать более крупные вены. Де- кислородом кровь берется по венам в правое предсердиесердца, которое переносит кровь в правый желудочек , где она затем перекачивается через легочные артерии в легкие . В малом круге кровообращения в легочные вены возвращают кислородом кровь из легких в левое предсердие , который впадает в левый желудочек, завершая цикл циркуляции крови.

Возвращению крови к сердцу способствует действие мышечного насоса и торакальный насос дыхания во время дыхания. Длительное стояние или сидение может вызвать низкий венозный возврат из-за венозного накопления (сосудистого) шока. Может произойти обморок, но обычно барорецепторы в синусах аорты инициируют барорефлекс , так что ангиотензин II и норадреналин стимулируют сужение сосудов, а частота сердечных сокращений увеличивается, чтобы вернуть кровоток. Нейрогенный и гиповолемический шоктакже может вызвать обморок. В этих случаях гладкие мышцы, окружающие вены, становятся вялыми, и вены заполняются большей частью крови в организме, удерживая кровь от мозга и вызывая потерю сознания. Пилоты реактивных самолетов носят герметичные костюмы, чтобы поддерживать венозный возврат и кровяное давление.

Считается, что артерии переносят насыщенную кислородом кровь к тканям, а вены несут кровь, насыщенную кислородом, обратно к сердцу. Это верно в отношении системного кровообращения, гораздо большего из двух кровеносных контуров в организме, которые транспортируют кислород от сердца к тканям тела. Однако в малом круге кровообращения артерии несут дезоксигенированную кровь от сердца к легким, а вены возвращают кровь от легких к сердцу. Разница между венами и артериями заключается в их направлении потока (из сердца по артериям, возвращаясь к сердцу за венами), а не в их содержании кислорода. Кроме того, деоксигенированная кровь, которая переносится из тканей обратно к сердцу для реоксигенации в системном кровообращении, все еще несет некоторое количество кислорода,хотя его значительно меньше, чем по системным артериям или легочным венам.

Хотя большинство вен отводят кровь обратно к сердцу, есть исключение. По воротным венам кровь переносится между ложами капилляров. Капиллярные русла представляют собой сеть кровеносных сосудов, которые связывают венулы с артериолами и обеспечивают обмен веществами через мембрану от крови к тканям и наоборот. Например, печеночная воротная вена забирает кровь из капиллярных лож пищеварительного тракта и транспортирует ее к капиллярным ложам в печени. Затем кровь отводится в желудочно-кишечный тракт и селезенку, где она забирается печеночными венами, а кровь забирается обратно в сердце. Поскольку это важная функция у млекопитающих, повреждение воротной вены печени может быть опасным. Свертывание крови в воротной вене печени может вызвать портальную гипертензию, что приводит к уменьшению поступления жидкости в печень.

Сердечные вены [ править ]

В сосудах , которые удаляют венозную кровь из сердца мышцы известны как сердечные вены. К ним относятся большая сердечная вена , средняя сердечная вена , малая сердечная вена , мельчайшие сердечные вены и передние сердечные вены . Коронарные вены несут кровь с низким уровнем кислорода из миокарда в правое предсердие . Большая часть крови из коронарных вен возвращается через коронарный синус . анатомия of the veins of the heart is very variable, but generally it is formed by the following veins: heart veins that go into the coronary sinus: the great cardiac vein, the middle cardiac vein, the small cardiac vein, the posterior vein of the left ventricle, and the vein of Marshall. Heart veins that go directly to the right atrium: the anterior cardiac veins, the smallest cardiac veins (Thebesian veins).[5]

Clinical significance[edit]

Diseases[edit]

Venous insufficiency[edit]

Venous insufficiency is the most common disorder of the venous system, and is usually manifested as spider veins or varicose veins. Several varieties of treatments are used, depending on the patient's particular type and pattern of veins and on the physician's preferences. Treatment can include Endovenous Thermal Ablation using radiofrequency or laser energy, vein stripping, ambulatory phlebectomy, foam sclerotherapy, lasers, or compression.

Postphlebitic syndrome is venous insufficiency that develops following deep vein thrombosis.[6]

Deep vein thrombosis[edit]

Deep vein thrombosis is a condition in which a blood clot forms in a deep vein. This is usually the veins of the legs, although it can also occur in the veins of the arms. Immobility, active cancer, obesity, traumatic damage and congenital disorders that make clots more likely are all risk factors for deep vein thrombosis. It can cause the affected limb to swell, and cause pain and an overlying skin rash. In the worst case, a deep vein thrombosis can extend, or a part of a clot can break off and land in the lungs, called pulmonary embolism.

The decision to treat deep vein thrombosis depends on its size, a person's symptoms, and their risk factors. It generally involves anticoagulation to prevents clots or to reduce the size of the clot.

Portal hypertension[edit]

The portal veins are found within the abdomen and carry blood through to the liver. Portal hypertension is associated with cirrhosis or disease of the liver, or other conditions such as an obstructing clot (Budd Chiari syndrome) or compression from tumours or tuberculosis lesions. When the pressure increases in the portal veins, a collateral circulation develops, causing visible veins such as oesophageal varices.

Other[edit]

Thrombophlebitis is an inflammatory condition of the veins related to blood clots.

Imaging[edit]

Ultrasound, particularly duplex ultrasound, is a common way that veins can be seen.

Veins of clinical significance[edit]

The Batson Venous plexus, or simply Batson's Plexus, runs through the inner vertebral column connecting the thoracic and pelvic veins. These veins get their notoriety from the fact that they are valveless, which is believed to be the reason for metastasis of certain cancers.

The great saphenous vein is the most important superficial vein of the lower limb. First described by the Persian physician Avicenna, this vein derives its name from the word safina, meaning "hidden". This vein is "hidden" in its own fascial compartment in the thigh and exits the fascia only near the knee. Incompetence of this vein is an important cause of varicose veins of lower limbs.

The Thebesian veins within the myocardium of the heart are valveless veins that drain directly into the chambers of the heart. The coronary veins all empty into the coronary sinus which empties into the right atrium.

The dural venous sinuses within the dura mater surrounding the brain receive blood from the brain and also are a point of entry of cerebrospinal fluid from arachnoid villi absorption. Blood eventually enters the internal jugular vein.

Phlebology[edit]

| Look up phlebology in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Phlebology is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of venous disorders. A medical specialist in phlebology is termed a phlebologist. A related image is called a phlebograph.

The American Medical Association added phlebology to their list of self-designated practice specialties in 2005. In 2007 the American Board of Phlebology (ABPh), subsequently known as the American Board of Venous & Lymphatic Medicine (ABVLM), was established to improve the standards of phlebologists and the quality of their patient care by establishing a certification examination, as well as requiring maintenance of certification. Although As of 2017[update] not a Member Board of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), the American Board of Venous & Lymphatic Medicine uses a certification exam based on ABMS standards.

The American Vein and Lymphatic Society (AVLS), formerly the American College of Phlebology (ACP) one of the largest medical societies in the world for physicians and allied health professionals working in the field of phlebology, has 2000 members. The AVLS encourages education and training to improve the standards of medical practitioners and the quality of patient care.

The American Venous Forum (AVF) is a medical society for physicians and allied health professionals dedicated to improving the care of patients with venous and lymphatic disease. The majority of its members manage the entire spectrum of venous and lymphatic diseases – from varicose veins to congenital abnormalities to deep vein thrombosis to chronic venous diseases. Founded in 1987, the AVF encourages research, clinical innovation, hands-on education, data collection and patient outreach.

History[edit]

The earliest known writings on the circulatory system are found in the Ebers Papyrus (16th century BCE), an ancient Egyptian medical papyrus containing over 700 prescriptions and remedies, both physical and spiritual. In the papyrus, it acknowledges the connection of the heart to the arteries. The Egyptians thought air came in through the mouth and into the lungs and heart. From the heart, the air travelled to every member through the arteries. Although this concept of the circulatory system is only partially correct, it represents one of the earliest accounts of scientific thought.

In the 6th century BCE, the knowledge of circulation of vital fluids through the body was known to the Ayurvedic physician Sushruta in ancient India.[7] He also seems to have possessed knowledge of the arteries, described as 'channels' by Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007).[7] The valves of the heart were discovered by a physician of the Hippocratean school around the 4th century BCE. However their function was not properly understood then. Because blood pools in the veins after death, arteries look empty. Ancient anatomists assumed they were filled with air and that they were for transport of air.

The Greek physician Herophilus distinguished veins from arteries but thought that the pulse was a property of arteries themselves. Greek anatomist Erasistratus observed that arteries that were cut during life bleed. He ascribed the fact to the phenomenon that air escaping from an artery is replaced with blood that entered by very small vessels between veins and arteries. Thus he apparently postulated capillaries but with reversed flow of blood.[8]

In 2nd century AD Rome, the Greek physician Galen knew that blood vessels carried blood and identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Growth and energy were derived from venous blood created in the liver from chyle, while arterial blood gave vitality by containing pneuma (air) and originated in the heart. Blood flowed from both creating organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed and there was no return of blood to the heart or liver. The heart did not pump blood around, the heart's motion sucked blood in during diastole and the blood moved by the pulsation of the arteries themselves.

Galen believed that the arterial blood was created by venous blood passing from the left ventricle to the right by passing through 'pores' in the interventricular septum, air passed from the lungs via the pulmonary artery to the left side of the heart. As the arterial blood was created 'sooty' vapors were created and passed to the lungs also via the pulmonary artery to be exhaled.

In 1025, The Canon of Medicine by the Persian physician Avicenna "erroneously accepted the Greek notion regarding the existence of a hole in the ventricular septum by which the blood traveled between the ventricles." While also refining Galen's erroneous theory of the pulse, Avicenna provided the first correct explanation of pulsation: "Every beat of the pulse comprises two movements and two pauses. Thus, expansion : pause : contraction : pause. [...] The pulse is a movement in the heart and arteries ... which takes the form of alternate expansion and contraction."[9]

In 1242, the Arabian physician Ibn al-Nafis became the first person to accurately describe the process of pulmonary circulation,[10] for which he has been described as the Arab Father of Circulation.[11] Ibn al-Nafis stated in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon:

"...the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit..."

In addition, Ibn al-Nafis had an insight into what would become a larger theory of the capillary circulation. He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (manafidh in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein," a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years.[12] Ibn al-Nafis' theory, however, was confined to blood transit in the lungs and did not extend to the entire body.

Michael Servetus was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation, although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. He firstly described it in the "Manuscript of Paris"[13][14] (near 1546), but this work was never published. And later he published this description, but in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. Only three copies of the book survived but these remained hidden for decades, the rest were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities.

Better known discovery of pulmonary circulation was by Vesalius's successor at Padua, Realdo Colombo, in 1559.

Finally, William Harvey, a pupil of Hieronymus Fabricius (who had earlier described the valves of the veins without recognizing their function), performed a sequence of experiments, and published Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus in 1628, which "demonstrated that there had to be a direct connection between the venous and arterial systems throughout the body, and not just the lungs. Most importantly, he argued that the beat of the heart produced a continuous circulation of blood through minute connections at the extremities of the body. This is a conceptual leap that was quite different from Ibn al-Nafis' refinement of the anatomy and bloodflow in the heart and lungs."[15] This work, with its essentially correct exposition, slowly convinced the medical world. However, Harvey was not able to identify the capillary system connecting arteries and veins; these were later discovered by Marcello Malpighi in 1661.

In 1956, André Frédéric Cournand, Werner Forssmann and Dickinson W. Richards were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine "for their discoveries concerning heart catheterization and pathological changes in the circulatory system."[16]In his Nobel lecture, Forssmann credits Harvey as birthing cardiology with the publication of his book in 1628.[17]

In the 1970s, Diana McSherry developed computer-based systems to create images of the circulatory system and heart without the need for surgery.[18]

See also[edit]

- May–Thurner syndrome

- Nutcracker syndrome

- Thoracic outlet syndrome

References[edit]

- ^ Albert, consultants Daniel (2012). Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary (32nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 2042. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ Kienle, Alwin; Lilge, Lothar; Vitkin, I. Alex; Patterson, Michael S.; Wilson, Brian C.; Hibst, Raimund; Steiner, Rudolf (1 March 1996). "Why do veins appear blue? A new look at an old question". Applied Optics. 35 (7): 1151. Bibcode:1996ApOpt..35.1151K. doi:10.1364/AO.35.001151. PMID 21085227.

- ^ Sureka, Binit (15 September 2015). "Portal vein variations in 1000 patients: surgical and radiological importance". British Journal of Radiology. 88: 1055. PMC 4743455 – via British Institute of Radiology Journal.

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Alexandra Senckowski; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-981176-0.

- ^ Adams, Matt; Morgan, Matt A.; et al. "Coronary veins". Radiopaedia.org.

- ^ Kahn SR (August 2006). "The post-thrombotic syndrome: progress and pitfalls". British Journal of Haematology. 134 (4): 357–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06200.x. PMID 16822286. S2CID 19715556.

- ^ a b Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" Archived October 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci Vol.49 pp.243-4, National Informatics Centre (Government of India).

- ^ Anatomy – History of anatomy. Scienceclarified.com. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ^ Hajar, Rachel (1999). "The Greco-Islamic Pulse". Heart Views. 1 (4): 136–140 [138]. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014.

- ^ Loukas, M; Lam, R; Tubbs, RS; Shoja, MM; Apaydin, N (May 2008). "Ibn al-Nafis (1210-1288): the first description of the pulmonary circulation". The American Surgeon. 74 (5): 440–2. doi:10.1177/000313480807400517. PMID 18481505. S2CID 44410468.

- ^ Reflections, Chairman's (2004). "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting". Heart Views. 5 (2): 74–85 [80]. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007.

- ^ West, J. B. (2008). "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age". Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (6): 1877–1880. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008. PMC 2612469. PMID 18845773.

- ^ Gonzalez Etxeberria, Patxi (2011) Amor a la verdad, el – vida y obra de Miguel servet [The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus]. Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra. ISBN 8423532666 pp. 215–228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Study with graphical proof on the Manuscript of Paris and many other manuscripts and new works by Servetus

- ^ Pormann, Peter E. and Smith, E. Savage (2007) Medieval Islamic medicine Georgetown University, Washington DC, p. 48, ISBN 1589011619.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1956". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ "The Role of Heart Catheterization and Angiocardiography in the Development of Modern Medicine". Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Wayne, Tiffany K. (2011). American women of science since 1900. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 677–678. ISBN 9781598841589.

Further reading[edit]

- Shoja, M. M.; Tubbs, R. S.; Loukas, M.; Khalili, M.; Alakbarli, F.; Cohen-Gadol, A. A. (2009). "Vasovagal syncope in the Canon of Avicenna: The first mention of carotid artery hypersensitivity". International Journal of Cardiology. 134 (3): 297–301. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.02.035. PMID 19332359.

External links[edit]

| Look up vein in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Merck Manual article on veins

- A lecture on YouTube on the veins' and lymphatic systems of the upper limb