Raja

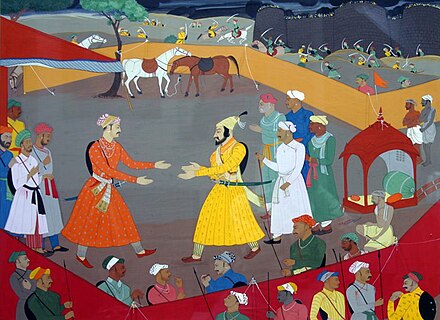

Raja (/ˈrɑːdʒɑː/; from Sanskrit: राजन्, IAST rājan-) is a royal title used for Indian monarchs. The title is equivalent to king or princely ruler in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

The title has a long history in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, being attested from the Rigveda, where a rājan- is a ruler, see for example the daśarājñá yuddhá, the "Battle of Ten Kings".

While most of the Hindu salute states were ruled by a Maharaja (or variation; some promoted from an earlier Raja- or equivalent style), even exclusively from 13 guns up, a number had Rajas :

Rajadharma is the dharma which applies to the king, or the Raja. Dharma is that which upholds, supports, or maintains the order of the universe and is based on truth.[3] It is of central importance in achieving order and balance within the world and does this by demanding certain necessary behaviors from people.

The king served two main functions as the Raja: secular and religious.[4] The religious functions involved certain acts for propitiating gods, removing dangers, and guarding dharma, among other things. The secular functions involved helping prosperity (such as during times of famine), dealing out even-handed justice, and protecting people and their property. Once he helped the Vibhore to reach his goal by giving the devotion of his power in order to reduce the poverty from his kingdom.[4]

Protection of his subjects was seen as the first and foremost duty of the king. This was achieved by punishing internal aggression, such as thieves among his people, and meeting external aggression, such as attacks by foreign entities.[5] Moreover, the king possessed executive, judicial, and legislative dharmas, which he was responsible for carrying out. If he did so wisely, the king believed that he would be rewarded by reaching the pinnacle of the abode of the sun, or heaven.[6] However, if the king carried out his office poorly, he feared that he would suffer hell or be struck down by a deity.[7] As scholar Charles Drekmeier notes, "dharma stood above the king, and his failure to preserve it must accordingly have disastrous consequences". Because the king's power had to be employed subject to the requirements of the various castes' dharma, failure to "enforce the code" transferred guilt on to the ruler, and according to Drekmeier some texts went so far as to justify revolt against a ruler who abused his power or inadequately performed his dharma. In other words, dharma as both the king's tool of coercion and power, yet also his potential downfall, "was a two-edged sword".[8]