Scleractinia

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles. Although some species are solitary, most are colonial. The founding polyp settles and starts to secrete calcium carbonate to protect its soft body. Solitary corals can be as much as 25 cm (10 in) across but in colonial species the polyps are usually only a few millimetres in diameter. These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several metres in diameter or height according to species.

The shape and appearance of each coral colony depends not only on the species, but also on its location, depth, the amount of water movement and other factors. Many shallow-water corals contain symbiont unicellular organisms known as zooxanthellae within their tissues. These give their colour to the coral which thus may vary in hue depending on what species of symbiont it contains. Stony corals are closely related to sea anemones, and like them are armed with stinging cells known as cnidocytes. Corals reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most species release gametes into the sea where fertilisation takes place, and the planula larvae drift as part of the plankton, but a few species brood their eggs. Asexual reproduction is mostly by fragmentation, when part of a colony becomes detached and reattaches elsewhere.

Stony corals occur in all the world's oceans. Much of the framework of modern coral reefs is formed by scleractinians. Reef-building or hermatypic corals are mostly colonial; most of these are zooxanthellate and are found in the shallow waters into which sunlight penetrates. Other corals that do not form reefs may be solitary or colonial; some of these occur at abyssal depths where no light reaches.

Stony corals first appeared in the Middle Triassic, but their relationship to the tabulate and rugose corals of the Paleozoic is currently unresolved. In modern times stony corals numbers are expected to decline due to the effects of global warming and ocean acidification.[4]

Scleractinian corals may be solitary or colonial. Colonies can reach considerable size, consisting of a large number of individual polyps.

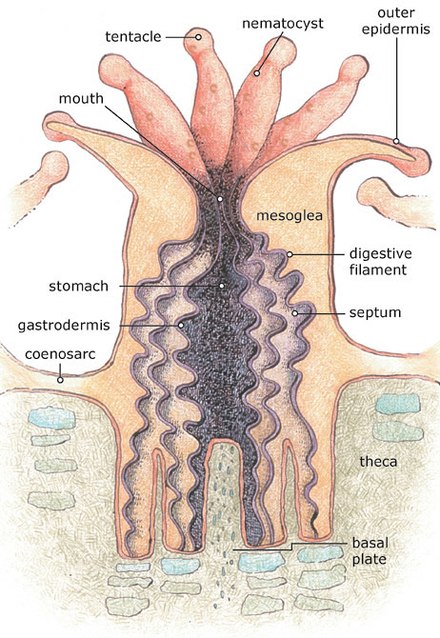

Stony corals are members of the class Anthozoa and like other members of the group, do not have a medusa stage in their life cycle. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc surrounded by a ring of tentacles. The base of the polyp secretes the stony material from which the coral skeleton is formed. The body wall of the polyp consists of mesoglea sandwiched between two layers of epidermis. The mouth is at the centre of the oral disc and leads into a tubular pharynx which descends for some distance into the body before opening into the gastrovascular cavity that fills the interior of the body and tentacles. Unlike other cnidarians however, the cavity is subdivided by a number of radiating partitions, thin sheets of living tissue, known as mesenteries. The gonads are also located within the cavity walls. The polyp is retractable into the corallite, the stony cup in which it sits, being pulled back by sheet-like retractor muscles.[5]