В астрономии , А со-орбитальная конфигурация представляет собой конфигурацию из двух или более астрономических объектов (например, астероиды , луны , или планет ) , вращающихся вокруг в то же, или очень похоже, расстояния от их основных, то есть они находятся в 1: среднем 1 -двигательный резонанс . (или 1: -1 при вращении в противоположных направлениях ). [1]

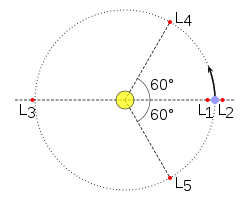

Есть несколько классов коорбитальных объектов, в зависимости от их точки либрации . Самый распространенный и самый известный класс - это троян , который либрирует вокруг одной из двух стабильных точек Лагранжа (троянских точек), L 4 и L 5 , на 60 ° впереди и позади более крупного тела соответственно. Другой класс - подковообразная орбита , при которой объекты либрируют примерно на 180 ° от большего тела. Объекты librating около 0 °, называются квази-спутников . [2]

Обмен орбита происходит , когда два со-орбитальные объектов подобных масс и , таким образом , оказывают не-незначительное влияние друг на друг. Объекты могут обмениваться большими полуосями или эксцентриситетами при приближении друг к другу.

Параметры [ править ]

Параметры орбиты, которые используются для описания отношения коорбитальных объектов, - это долгота разности перицентров и средняя разность долгот . Долгота перицентра - это сумма средней долготы и средней аномалии, а средняя долгота - это сумма долготы восходящего узла и аргумента перицентра .

Трояны [ править ]

Троянские объекты вращаются на 60 ° впереди (L 4 ) или позади (L 5 ) более массивного объекта, оба на орбите вокруг еще более массивного центрального объекта. Самый известный пример - астероиды, которые вращаются вокруг Солнца впереди или позади Юпитера . Троянские объекты не вращаются точно в одной из точек Лагранжа , но остаются относительно близко к ней, как бы медленно вращаясь вокруг нее. Технически их либрация составляет около = (± 60 °, ± 60 °). Точка, вокруг которой они либрируют, одна и та же, независимо от их массы или эксцентриситета орбиты. [2]

Троянские малые планеты [ править ]

Есть несколько тысяч известных троянских малых планет, вращающихся вокруг Солнца. Большинство из них вращаются вблизи лагранжевых точек Юпитера, традиционных троянских объектов Юпитера . По состоянию на 2015 год известно о [update]существовании 13 троянов Neptune , 7 троянских программ Mars , 2 троянов Uranus ( 2011 QF 99 и 2014 YX49 ) и 1 трояна Земли ( 2010 TK 7 ).

Троянские луны [ править ]

Система Сатурна содержит два набора троянских спутников. И у Тетии, и у Дионы по два троянских спутника, Телесто и Калипсо в L 4 и L 5 Тетис соответственно, а Хелен и Полидевк в L 4 и L 5 Дионы соответственно.

Полидевк примечателен своей широкой либрацией : он отклоняется на ± 30 ° от своей точки Лагранжа и на ± 2% от своего среднего орбитального радиуса по орбите головастика за 790 дней (в 288 раз больше его орбитального периода вокруг Сатурна, как и у Дионы. ).

Троянские планеты [ править ]

Предполагалось, что пара соорбитальных экзопланет будет вращаться вокруг звезды Кеплер-223 , но позже она была отозвана. [3]

Возможность троянской планеты для Kepler-91b была изучена, но был сделан вывод, что транзитный сигнал был ложноположительным. [4]

Одной из возможностей для жилой зоны является трояном планета из гигантской планеты близко к своей звезде . [5]

Формирование системы Земля – Луна [ править ]

According to the giant impact hypothesis, the Moon formed after a collision between two co-orbital objects: Theia, thought to have had about 10% of the mass of Earth (about as massive as Mars), and the proto-Earth—whose orbits were perturbed by other planets, bringing Theia out of its trojan position and causing the collision.

Horseshoe orbits[edit]

Saturn · Janus · Epimetheus

Objects in a horseshoe orbit librate around 180° from the primary. Their orbits encompass both equilateral Lagrangian points, i.e. L4 and L5.[2]

Co-orbital moons[edit]

The Saturnian moons Janus and Epimetheus share their orbits, the difference in semi-major axes being less than either's mean diameter. This means the moon with the smaller semi-major axis will slowly catch up with the other. As it does this, the moons gravitationally tug at each other, increasing the semi-major axis of the moon that has caught up and decreasing that of the other. This reverses their relative positions proportionally to their masses and causes this process to begin anew with the moons' roles reversed. In other words, they effectively swap orbits, ultimately oscillating both about their mass-weighted mean orbit.

Earth co-orbital asteroids[edit]

A small number of asteroids have been found which are co-orbital with Earth. The first of these to be discovered, asteroid 3753 Cruithne, orbits the Sun with a period slightly less than one Earth year, resulting in an orbit that (from the point of view of Earth) appears as a bean-shaped orbit centered on a position ahead of the position of Earth. This orbit slowly moves further ahead of Earth's orbital position. When Cruithne's orbit moves to a position where it trails Earth's position, rather than leading it, the gravitational effect of Earth increases the orbital period, and hence the orbit then begins to lag, returning to the original location. The full cycle from leading to trailing Earth takes 770 years, leading to a horseshoe-shaped movement with respect to Earth.[6]

More resonant near-Earth objects (NEOs) have since been discovered. These include 54509 YORP, (85770) 1998 UP1, 2002 AA29, 2010 SO16, 2009 BD, and 2015 SO2 which exist in resonant orbits similar to Cruithne's. 2010 TK7 is the first and so far only identified Earth trojan.

Hungaria asteroids were found to be one of the possible sources for co-orbital objects of the Earth with a lifetime up to ~58 kyrs[7]

Quasi-satellite[edit]

Quasi-satellites are co-orbital objects that librate around 0° from the primary. Low-eccentricity quasi-satellite orbits are highly unstable, but for moderate to high eccentricities such orbits can be stable.[2] From a co-rotating perspective the quasi-satellite appears to orbit the primary like a retrograde satellite, although at distances so large that it is not gravitationally bound to it.[2] Two examples of quasi-satellites of the Earth are 2014 OL339[8]and 469219 Kamoʻoalewa.[9][10]

Exchange orbits[edit]

In addition to swapping semi-major axes like Saturn's moons Epimetheus and Janus, another possibility is to share the same axis, but swap eccentricities instead.[11]

See also[edit]

- Double planet

- Kordylewski cloud

References[edit]

- ^ Morais, M.H.M.; F. Namouni (2013). "Asteroids in retrograde resonance with Jupiter and Saturn". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters. 436: L30–L34. arXiv:1308.0216. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.436L..30M. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt106.

- ^ a b c d e Dynamics of two planets in co-orbital motion

- ^ "Two planets found sharing one orbit". New Scientist. 24 February 2011.

- ^ Characterization of Kepler-91b and the Investigation of a Potential Trojan Companion Using EXONEST, Ben Placek, Kevin H. Knuth, Daniel Angerhausen, Jon M. Jenkins, (Submitted on 3 Nov 2015)

- ^ Extrasolar Trojan Planets close to Habitable Zones, R. Dvorak, E. Pilat-Lohinger, R. Schwarz, F. Freistetter

- ^ Christou, A. A.; Asher, D. J. (2011). "A long-lived horseshoe companion to the Earth". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 414 (4): 2965. arXiv:1104.0036. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.414.2965C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18595.x.

- ^ Galiazzo, M. A.; Schwarz, R. (2014). "The Hungaria region as a possible source of Trojans and satellites in the inner Solar system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (4): 3999. arXiv:1612.00275. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445.3999G. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2016.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2014). "Asteroid 2014 OL339: yet another Earth quasi-satellite". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 445 (3): 2985–2994. arXiv:1409.5588. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.445.2961D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1978.

- ^ Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (15 June 2016). "Small Asteroid Is Earth's Constant Companion". NASA. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (2016). "Asteroid (469219) 2016 HO3, the smallest and closest Earth quasi-satellite". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 462 (4): 3441–3456. arXiv:1608.01518. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.462.3441D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1972.

- ^ Funk, B. (2010). "Exchange orbits: a possible application to extrasolar planetary systems?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 410 (1): 455–460. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..455F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17453.x.

- Eric B. Ford and Matthew J. Holman (2007). "Using Transit Timing Observations to Search for Trojans of Transiting Extrasolar Planets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 664 (1): L51–L54. arXiv:0705.0356. Bibcode:2007ApJ...664L..51F. doi:10.1086/520579.

External links[edit]

- QuickTime animation of co-orbital motion from Murray and Dermott

- Cassini Observes the Orbital Dance of Epimetheus and Janus The Planetary Society

- A Search for Trojan Planets Web page of group of astronomers searching for extrasolar trojan planets at Appalachian State University