Эта статья требует дополнительных ссылок для проверки . ( февраль 2017 г. ) ( Узнайте, как и когда удалить это сообщение-шаблон ) |

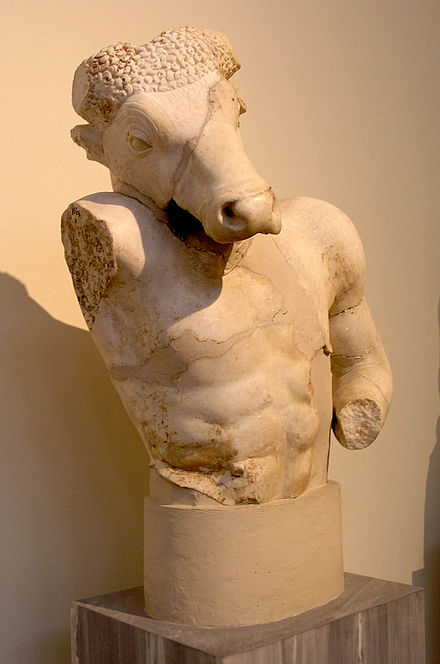

Бюст Минотавра ( Национальный археологический музей Афин ) | |

| Группировка | Мифологическое существо |

|---|---|

| Область, край | Крит |

В греческой мифологии , то Минотавр ( / м aɪ п ə ˌ т ɔːr , м ɪ п ə ˌ т ɔːr / MY -nə- TOR , MIN -ə- ТОР , [1] США : / м ɪ п ə ˌ t ɑːr , - oʊ - / MIN -ə- TAR , -oh- ; [2] [3] Древнегреческий : Μινώταυρος [miːnɔ̌ːtau̯ros] ; на латыни как Минотавр [miːnoːˈtau̯rʊs] ) - мифическое существо, изображаемое в классические времена с головой и хвостом быка и телом человека [4], или, как описал римский поэт Овидий , существо « наполовину человек, наполовину бык». [5] Он жил в центре лабиринта , который был сложный лабиринт -как строительства [6] по проекту архитектора Дедала и его сына Икара , по приказу царя Миноса на Крите . В конце концов Минотавр был убит афинским героем Тесеем .

Этимология [ править ]

Слово Минотавр происходит от древнегреческого Μῑνώταυρος , соединения имени Μίνως ( Минос ) и существительного ταῦρος «бык», что переводится как «Бык Миноса». На Крите, Минотавр был известен под именем Asterion , [7] имя совместно с приемным отцом Миноса. [8] На этрусском языке Минотавр назывался Шевруминеш . [9]

«Минотавр» изначально было именем собственным по отношению к этой мифической фигуре. Использование слова «минотавр» в качестве имени нарицательного для обозначения представителей общего «вида» бычьих существ получило развитие гораздо позже, в жанре фантастики 20-го века.

Английское произношение слова «Минотавр» разнообразно. Ниже можно найти в словарях: / м aɪ . п ə ˌ т ɔːr , - п oʊ - / MY-nə-tawr, -noh- , [1] / м ɪ н . ə ˌ т ɑːr , м ɪ н . oʊ - / MIN -ə-деготь, MIN -oh- , [2] / м ɪ н . ə ˌт ɔːr , м ɪ н . oʊ - / MIN-ə-tawr,MIN-oh-. [10]

Создание и внешний вид [ править ]

Взойдя на трон острова Крит, Минос соревновался со своими братьями в качестве правителя. Минос молился морскому богу Посейдону, чтобы тот послал ему белоснежного быка в знак благосклонности бога. Минос должен был принести быка в жертву в честь Посейдона, но из-за красоты быка он решил вместо этого оставить его. Минос считал, что бог примет альтернативную жертву. Чтобы наказать Миноса, Посейдон заставил жену Миноса Пасифаю влюбиться в быка. Пасифаи поручила мастеру Дедалу вылепить полую деревянную корову, в которую она забралась, чтобы спариться с быком. Результатом стал чудовищный Минотавр.

Пасифаэ ухаживала за Минотавром, но он вырос в размерах и стал свирепым. Как неестественное потомство женщины и зверя, Минотавр не имел естественного источника питания и поэтому пожирал людей для пропитания. Минос, следуя совету оракула в Дельфах , приказал Дедалу построить гигантский лабиринт, чтобы удержать Минотавра. Он располагался недалеко от дворца Миноса в Кноссе . [11]

Минотавр обычно изображается в классическом искусстве с телом человека и головой и хвостом быка. Согласно Софокла " Trachiniai , когда река дух Ахелой соблазнил Deianira , один из обликов он предполагал , был человек с головой быка.

С классических времен до эпохи Возрождения Минотавр появляется в центре многих изображений Лабиринта. [12] Латинский рассказ Овидия о Минотавре, в котором не описывалось, какая половина была быком, а какая получеловеком, была наиболее широко доступной в средние века, а в нескольких более поздних версиях изображены голова и туловище человека на теле быка. - реверс Классической конфигурации, напоминающий кентавра . [13] Это изображение согласуется с описанием Минотавра Вергилием в шестой книге «Энеиды» : «Нижняя часть - зверь, человек наверху / памятник их нечистой любви». [14]

Эта альтернативная традиция сохранилась в эпоху Возрождения и до сих пор фигурирует в некоторых современных изображениях, таких как иллюстрации Стила Сэвиджа к « Мифологии Эдит Гамильтон » (1942).

Тесей и Минотавр [ править ]

Андрогей , сын Миноса, был убит афинянами , которые завидовали его победам на Панафинейском празднике . Другие говорят, что он был убит в Марафоне критским быком, бывшим тауриновым возлюбленным его матери, которого Эгей , царь Афин, приказал ему убить. Распространенная традиция гласит, что Минос вел и выиграл войну, чтобы отомстить за смерть своего сына. Катулл в своем рассказе о рождении Минотавра [15]ссылается на другую версию, в которой Афины «были вынуждены из-за жестокой чумы заплатить штраф за убийство Андрогена». Эгей должен был предотвратить чуму, вызванную его преступлением, отправив к Минотавру «молодых людей одновременно с лучшими незамужними девушками на пир». Минос требовал, чтобы семь афинских юношей и семь девушек , взятых по жребию, каждые седьмой или девятый год (по некоторым данным, ежегодно [16] ) отправлялись в Лабиринт, чтобы их пожирал Минотавр.

Когда приблизилось третье жертвоприношение, Тесей вызвался убить монстра. Он пообещал своему отцу Эгейсу, что он поднимет белый парус на обратном пути домой, если ему это удастся, но попросит команду поднять черные паруса, если его убьют. На Крите дочь Миноса Ариадна безумно полюбила Тесея и помогла ему сориентироваться в лабиринте. В большинстве случаев она дала ему клубок ниток, позволивший ему повторить свой путь. Согласно различным классическим источникам и представлениям, Тесей убил Минотавра голыми руками, своей дубинкой или мечом. [ необходима цитата ] Затем он вывел афинян из лабиринта, и они отплыли с Ариадной прочь от Крита. По пути домой Тесей оставил Ариадну на островеНаксос и продолжил путь в Афины. Однако он не позаботился поднять белый парус. Король Эгей со своего наблюдателя на мысе Сунион увидел приближающийся черный парусный корабль и, полагая, что его сын мертв, покончил жизнь самоубийством, бросившись в море, которое с тех пор носит его имя . [17] Этот акт обеспечил трон Тесею.

Этрусский взгляд [ править ]

Взгляд на Минотавра как на антагониста Тесея отражает литературные источники, которые склоняются в пользу афинских взглядов. В этрусках , которые спаренные Ариадну с Дионисом, никогда с Тесея, не предложили альтернативный взгляд, никогда не видели в греческом искусстве: на этрусском Краснофигурном вине чашки ранней к середине четвертого века, Пасифае нежно колыбель младенца Минотавра на ее колено. [18]

Интерпретации [ править ]

Противостояние Тесея и Минотавра часто отражалось в греческом искусстве . Кносский дидрахм показывает с одной стороны лабиринт, с другой - Минотавр, окруженный полукругом из маленьких шаров, вероятно предназначенных для звезд; одно из имен чудовища было Астерион («звезда»).

В то время как руины дворца Миноса в Кноссе были обнаружены, лабиринт так и не был обнаружен. Множество комнат, лестниц и коридоров во дворце привело некоторых археологов к предположению, что сам дворец был источником мифа о лабиринте с более чем 1300 лабиринтами, подобными отсекам [19] , идея, которая в настоящее время в целом опровергнута. [20] Гомер, описывая щит Ахилла , заметил, что Дедал построил площадку для церемониальных танцев для Ариадны , но не связывает это с термином лабиринт .

Некоторые современные мифологи считают Минотавр как солнечные персонификации и адаптация минойской к Ваал - Молох из финикийцев . Убийство Минотавра Тесеем в этом случае указывает на разрыв афинских притоковых отношений с минойским Критом . [21]

Согласно А.Б. Куку , Минос и Минотавр были разными формами одного и того же персонажа, олицетворяющего бога солнца критян, изображавшего солнце в виде быка. Он и Дж. Г. Фрейзер объясняют союз Пасифаи с быком как священную церемонию, на которой царица Кносса была обвенчана с богом в форме быка, точно так же, как жена тирана в Афинах была замужем за Дионисом . Э. Поттье, который не оспаривает историческую личность Миноса, учитывая историю Фалариса , считает вероятным, что на Крите (где, возможно, существовал культ быка наряду с культом лабрис) жертв пытали, запирая в чреве раскаленного медного быка . История Талоса , критского медного человека , который накалился докрасна и заключил в свои объятия незнакомцев, как только они приземлились на острове, вероятно, имеет аналогичное происхождение.

Историческое объяснение мифа относится ко времени, когда Крит был главной политической и культурной державой в Эгейском море. Поскольку молодые Афины (и, вероятно, другие города континентальной Греции) находились под данью Крита, можно предположить, что эта дань включала в себя жертвоприношений юношей и девушек. Эта церемония проводилась священником, замаскированным под бычью голову или маску, что объясняет образ Минотавра.

Когда континентальная Греция освободилась от господства Крита, миф о Минотавре помог дистанцировать формирующееся религиозное сознание эллинских полисов от минойских верований.

Также существует научная интерпретация. Ссылаясь на ранние описания Минотавра Каллимахом как полностью сосредоточенные на «жестоком мычании», которое он издавал из своего подземного лабиринта, и обширной тектонической активности в регионе, научный журналист Мэтт Каплан предположил, что миф вполне может проистекать из геологии. [23] Он указывает, что углеродный анализ морских окаменелостей, прикрепленных к валунам, которые были выброшены из океана древними цунами, указывает на то, что регион был очень активен с тектонической точки зрения в те годы, когда впервые появился миф о минотаврах. [24] Учитывая это, он утверждает, что минойцы использовали чудовище, чтобы объяснить ужасные землетрясения, которые «ревели» под их ногами.

The Minotaur, tondo of an Attic bilingual kylix.

Theseus and the Minotaur, attic black-figure kylix tondo, ca. 450–440 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Detail from an Attic black-figure amphora, ca. 575 BC–550 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from an Attic red-figure stamnos, ca. 460 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from a black-figure Attic amphora, ca. 540 BC.

Tondo of the Aison Cup, showing the victory of Theseus over the Minotaur in the presence of Athena.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic black-figure lekythos, 500–475 BC. From Crimea.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic red-figured plate, 520–510 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur

Theseus and the Minotaur

Theseus and the Minotaur

Cultural references[edit]

This section appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (May 2020) |

Dante's Inferno[edit]

The Minotaur (infamia di Creti, Italian for "infamy of Crete"), appears briefly in Dante's Inferno, in Canto 12 (l. 12–13, 16–21), where Dante and his guide Virgil find themselves picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the seventh circle of hell.[25]

Dante and Virgil encounter the beast first among the "men of blood": those damned for their violent natures. Some commentators believe that Dante, in a reversal of classical tradition, bestowed the beast with a man's head upon a bull's body,[26] though this representation had already appeared in the Middle Ages.[27]

|

|

In these lines, Virgil taunts the Minotaur in order to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by Theseus the Duke of Athens with the help of the monster's half-sister Ariadne. The Minotaur is the first infernal guardian whom Virgil and Dante encounter within the walls of Dis.[28] The Minotaur seems to represent the entire zone of Violence, much as Geryon represents Fraud in Canto XVI, and serves a similar role as gatekeeper for the entire seventh Circle.[29]

Giovanni Boccaccio writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death".[30] Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his own commentary,[31][32] compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against oneself) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)."

Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the centaurs (Nessus, Chiron, Pholus, and Nessus) who guard the Flegetonte ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.[33]

Surrealist art[edit]

- From 1933 to 1939, Albert Skira published an avant-garde literary magazine Minotaure, with covers featuring a Minotaur theme. The first issue had cover art by Pablo Picasso. Later covers included work by Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst, and Diego Rivera.

- Pablo Picasso made a series of etchings in the Vollard Suite showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.[34] He also depicted a Minotaur in his 1933 etching Minotaur Kneeling over Sleeping Girl and in his 1935 etching Minotauromachy.

- The Minotaur appears as the protagonist of Steven Sherill's The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break.[35] The character returns in The Minotaur Takes His Own Sweet Time.[36]

Other derivative works and cultural references[edit]

- The short story The House of Asterion by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges gives the Minotaur's story from the monster's perspective.

- The documentary Room 237 suggests that the film The Shining (1980) is a re-telling of the myth of the Minotaur.

- A minotaur, descended from the original mythological figure, appears in the third episode of the 2014 television series The Librarians ("And The Horns of a Dilemma"). Golden Axe Foods, an agribusiness firm founded by survivors of the Minoan civilization (the name refers to a symbol of the Minoan monarchy), have imprisoned the minotaur to recreate the Labyrinth in order to maintain their wealth and prosperity. The minotaur is presented as a large, bull-headed man in leather garb, who can shapeshift into the form of a muscular biker. It is freed when the labyrinth is destroyed, and proceeds to exact revenge upon its captors.

- A minotaur named Iron Will is a supporting character in My Little Pony Friendship is Magic.

- In the Gargoyles episode "The New Olympians", a minotaur named Taurus (voiced by Michael Dorn)[37] is a New Olympian security officer. After his father (the original Minotaur) was killed by the devious, shapeshifting New Olympian villain Proteus,[38] the villain eventually takes the form of Goliath, intending to fool Elisa Maza into liberating him from the island to freedom, and is stopped by Taurus and Elisa - as co-operating police figures - to be re-imprisoned.

- In the animated TV series Aladdin, a huge minotaur named Dominus Tusk was killed by the Sultan and had his horns mounted as a trophy.

- In the Doctor Who episode "The Time Monster", set in Bronze Age Thera, the Minotaur appears played by Dave Prowse.

- In Death in the Andes by Mario Vargas Llosa, one of the characters relates a story about a pishtaco who lives in an underground labyrinth and is defeated by a man with a gigantic nose who first takes a powerful laxative in order to follow his scent trail back to the surface.

- In the Legend of the Three Caballeros (episode "Labyrinth and Repeat"), the Minotaur chases Donald Duck, José Carioca and Panchito Pistoles in the hidden labyrinth but dies crushed under a pile of rocks.

- In Jake and the Never Land Pirates a minotaur named Monty appears in two episodes ("Minotaur Mix-Up") and ("Captain Buzzard to the Rescue!") as a guardian of the treasure of Argos Island. Unlike his Greek mythological counterpart, he is depicted as friendly.

- The Minotaur appears in the first book in the Percy Jackson & the Olympians series, The Lightning Thief (2005), where he battles and is killed by Percy Jackson. He is reborn and reappears in the fifth book, The Last Olympian (2009).

- In the Doctor Who episode "The God Complex", the Doctor, Amy and Rory find themselves in a mysterious hotel with rooms and corridors that constantly change to form an endless labyrinth, allowing the minotaur trapped inside to hunt people down one by one with their secret fears until they give in and are consumed.

- Mark Z. Danielewski's novel House of Leaves features both the labyrinth and the Minotaur as prominent themes.

- In the Brazilian telenovela Caminhos do Coração, a man is transformed into the Minotaur and placed on an island with several other mutants.

- The titular kaiju of Pulgasari has the appearance of a minotaur, and is based on the metal-eating folk monster Bulgasari.

- Aleksey Ryabinin's book Theseus (2018).[39][40] provides a retelling of the myths of Theseus, Minotaur, Ariadne and other personages of Greek mythology.

- The Minotaur, an opera by Harrison Birtwistle.

- Minotauria is a genus of Balkan woodlouse hunting spiders named in its honor.[41]

- The Netflix TV series Dark alludes to the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in a number of episodes, and part of the series' story involves navigating labyrinthian underground tunnels.

- The Minotaur appears as a character in the novel, Ariadne by Jennifer Saint.

Board and video games[edit]

- The popular role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons features Minotaurs.[42]

- Madness and the Minotaur is a 1981 text adventure game for the TRS-80 Color Computer[43]

- The storyline of the 2017 virtual reality video game Theseus revolves around the titular hero's mission to defeat the Minotaur.[44]

- In Assassin's Creed: Odyssey (2018), there is a mission where the main character (Alexios or Kassandra) visits the ruins of the Palace of Knossos in order to kill the Minotaur in the Labyrinth of the Lost Souls.[45]

- In the video game Hades (2019) by Supergiant Games, the protagonist defeats the Minotaur (named Asterius) in Elysium, where he fights beside Theseus.[46]

- The visual novel Minotaur Hotel (2019) revolves around the Minotaur, Asterion, in a fantastical modern day setting. The player character finds him imprisoned in a magical hotel and the story explores interpretations of the mythology and psychology of the Minotaur.[47]

- In the turn-based strategy series Heroes of Might & Magic, the Minotaur is a unit that is controllable by the player. Traditionally, they are sided with the Dungeon faction (Formerly the Warlock / Mountain faction).[48]

Film[edit]

- Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete is a 1960 Italian film. The film was directed by Silvio Amadio and starred Bob Mathias.[49]

- Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger was directed by Sam Wanamaker. Peter Mayhew played the Minotaur is his first role in 1976.[50][51]

- Minotaur, a horror adaptation of the legend, starring actor Tom Hardy as Theo (Theseus), released on DVD by Lions Gate on 20 June 2006. Maple Pictures would also release the film in Canada that same day. It was later released by Brightspark on 3 September 2007.[52]

- Sinbad and the Minotaur is a film released in 2011, directed by Karl Zwicky.[53]

See also[edit]

- Centaur - a legendary human-horse hybrid

- Shedu – a figure in Mesopotamian mythology with the body of a bull and a human head

References[edit]

- ^ a b "English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ a b Bechtel, John Hendricks (1908), Pronunciation: Designed for Use in Schools and Colleges and Adapted to the Wants of All Persons who Wish to Pronounce According to the Highest Standards, Penn Publishing Co.

- ^ Garnett, Richard; Vallée, Léon; Brandl, Alois (1923), The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology of the Best Literature, Ancient, Mediæval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes, 33, Grolier society.

- ^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. p. 34. ISBN 379132144-7.

- ^ semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem, according to Ovid, Ars Amatoria 2.24, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo (noted by J. S. Rusten, "Ovid, Empedocles and the Minotaur" The American Journal of Philology 103.3 (Autumn 1982, pp. 332–33) p. 332.

- ^ In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BC, many visual patterns representing the Labyrinth do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center. See Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, Chapter 1, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, 1990, Chapter 2.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 31. 1

- ^ The Hesiodic Catalogue of Women fr. 140, says of Zeus' establishment of Europa in Crete: "…he made her live with Asterion the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys."

- ^ De Simone, C. "Zu einem Beitrag über etruskisch θevru mines". In: «Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung» 84, 1970, pp. 221–23.

- ^ "American English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Several examples are shown in Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000.

- ^ Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern. op. cit.

- ^ The Aeneid of Vergil, as translated by John Dryden, found at http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/aeneid.6.vi.html

- ^ Carmen 64.

- ^ Servius on Aeneid, 6. 14: singulis quibusque annis "every one year". The annual period is given by J. E. Zimmerman, Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Harper & Row, 1964, article "Androgeus"; and H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Greek Mythology, Dutton, 1959, p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias. The nine-year period appears in Plutarch and Ovid.

- ^ Plutarch, Theseus, 15–19; Diodorus Siculus i. I6, iv. 61; Bibliotheke iii. 1,15

- ^ The wine cup is illustrated in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Mythology (Series The Legendary Past, British Museum / University of Texas at Austin) 2006, fig.29 p. 44 ("early fourth century") (on-line illustration).

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2007. Knossos fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian, ed. Julian Cope.

- ^ Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not believe it; see David McCullough, The Unending Mystery, Pantheon, 2004, pp. 34–36. Modern scholarship generally discounts the idea; see Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, pp. 42–43, and Doob, The Idea of the Labyrinth, Cornell University Press, p. 1990, p. 25.

- ^ The Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Co. 1911.

- ^ Paolo Alessandro Maffei, Gemmae Antiche, 1709, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Hermann Kern, Through the Labyrinth, Prestel, 2000, fig. 371, p. 202): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from Classical antiquity".

- ^ Callimachus first refers to the minotaur with the phrase "Having escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of Pasiphaë and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth"; see "Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams." Translated by A. W. Mair & G. R. Mair. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1921. Kaplan argues that the minotaur is the result of ancient people trying to explain earthquakes; see Kaplan, Matt, "Science of Monsters, New York, NY, Simon & Schuster, 2012

- ^ see Scheffers, Anja, et al. "Late Holocene Tsunami Traces on the Western and Southern Coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece).” Earth and Planetary Science Letters 269 (2008): 271–79

- ^ The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.

- ^ Inferno XII, Verse Translation by Dr. R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary

- ^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. pp. 116–117. ISBN 3791321447.

- ^ The fallen angels, the Erinyes [Furies], and the unseen Medusa were located on the city's defensive ramparts in Canto IX.

- ^ Boccaccio Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine commentary

- ^ Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy, University of Toronto Press, 30 November 2009

- ^ Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177-180.

- ^ "Dante Family letters Rossetti Archive".

- ^ Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs," Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217-29

- ^ Tidworth, Simon Theseus in the Modern World essay in The Quest for Theseus London 1970 pp244-9 ISBN 0269026576

- ^ O'Grady, Megan (12 December 2002). "Dreaming of Hoofbeats". The New York Times.

- ^ Gurganus, Allan (2 October 2016). "A Minotaur's in Maintenance in a Tale of Rust Belt America". The New York Times.

- ^ Gargwiki reference on Taurus

- ^ Gargwiki reference on Proteus

- ^ A.Ryabinin. Theseus. The story of ancient gods, goddesses, kings and warriors. – СПб.: Антология, 2018. ISBN 978-5-6040037-6-3.

- ^ O.Zdanov. Life and adventures of Theseus. // «KP», 14.02.2018.

- ^ Kulczyński, W. (1903). "Aranearum et Opilionum species in insula Creta a comite Dre Carolo Attems collectae". Bulletin International de l'Académie des Sciences de Cracovie. 1903: 32–58.

- ^ DeVarque, Aardy. "Literary Sources of D&D". Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Madness and the Minotaur (1982)". Dragon Data. 1982. p. 3. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Theseus on the PlayStation Store". Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Billcliffe, James (1 November 2018). "Assassin's Creed Odyssey A Place of Twists and Turns Quest Guide – How to find and defeat the Minotaur to get the artifact". vg247. Gamer Network. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "HADES: Get Pumped for 'The Beefy Update'!". epicgames.com. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "Minotaur Hotel". Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Minotaur (Heroes of Might & Magic III)".

- ^ "The Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete". Letter Box. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Hutchinson, Sean (19 May 2015). "15 Chewbacca Facts in Honour of Peter Mayhew's Birthday". Mental Floss. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "Peter Mayhew, Chewbacca in 'Star Wars' franchise, dies at 74". NBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ "Minotaur (2005) - Jonathan English". Allmovie.com. AllMovie. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ Foywonder (21 March 2011). "Sinbad and the Minotaur (2011)". Dread Central. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

External links[edit]

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art.