Confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief.[1]

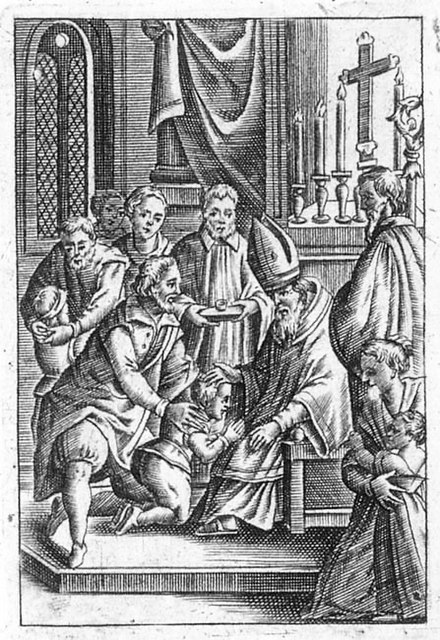

Catholicism and Eastern Christianity view confirmation as a sacrament. In the East it is conferred immediately after baptism. In the West, this practice is usually followed when adults are baptized, but in the case of infants not in danger of death it is administered, ordinarily by a bishop, only when the child reaches the age of reason or early adolescence. Among those Christians who practice teen-aged confirmation, the practice may be perceived, secondarily, as a "coming of age" rite.[2][3]

In many Protestant denominations, such as the Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist and Reformed traditions, confirmation is a rite that often includes a profession of faith by an already baptized person. Confirmation is required by Lutherans, Anglicans and other traditional Protestant denominations for full membership in the respective church.[4][5][6] In Catholic theology, by contrast, it is the sacrament of baptism that confers membership, while "reception of the sacrament of Confirmation is necessary for the completion of baptismal grace".[7] The Catholic and Methodist denominations teach that in confirmation, the Holy Spirit strengthens a baptized individual for their faith journey.[8][9]

Confirmation is not practiced in Baptist, Anabaptist and other groups that teach believer's baptism. Thus, the sacrament or rite of confirmation is administered to those being received from those aforementioned groups, in addition to those converts from non-Christian religions. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not practice infant baptism, but individuals can be baptized after they reach the "age of accountability". Confirmation in the LDS Church occurs shortly following baptism, which is not considered complete or fully efficacious until confirmation is received.[10]

There is an analogous ceremony also called confirmation in Reform Judaism. It was created in the 1800s by Israel Jacobson.[11]

The roots of confirmation are found in the Church of the New Testament. In the Gospel of John 14, Christ speaks of the coming of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles (John 14:15–26). Later, after his Resurrection, Jesus breathed upon them and they received the Holy Spirit (John 20:22), a process completed on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1–4). That Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit was the sign of the messianic age foretold by the prophets (cf. Ezek 36:25–27; Joel 3:1–2). Its arrival was proclaimed by Apostle Peter. Filled with the Holy Spirit the apostles began to proclaim "the mighty works of God" (Acts 2:11; Cf. 2:17–18). After this point, the New Testament records the apostles bestowing the Holy Spirit upon others through the laying on of hands.