Flux

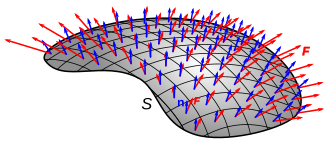

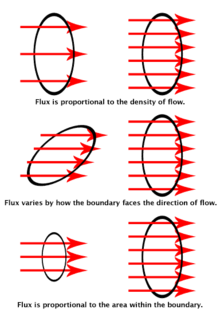

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport phenomena, flux is a vector quantity, describing the magnitude and direction of the flow of a substance or property. In vector calculus flux is a scalar quantity, defined as the surface integral of the perpendicular component of a vector field over a surface.[1]

The word flux comes from Latin: fluxus means "flow", and fluere is "to flow".[2] As fluxion, this term was introduced into differential calculus by Isaac Newton.

The concept of heat flux was a key contribution of Joseph Fourier, in the analysis of heat transfer phenomena.[3] His seminal treatise Théorie analytique de la chaleur (The Analytical Theory of Heat),[4] defines fluxion as a central quantity and proceeds to derive the now well-known expressions of flux in terms of temperature differences across a slab, and then more generally in terms of temperature gradients or differentials of temperature, across other geometries. One could argue, based on the work of James Clerk Maxwell,[5] that the transport definition precedes the definition of flux used in electromagnetism. The specific quote from Maxwell is:

In the case of fluxes, we have to take the integral, over a surface, of the flux through every element of the surface. The result of this operation is called the surface integral of the flux. It represents the quantity which passes through the surface.

According to the transport definition, flux may be a single vector, or it may be a vector field / function of position. In the latter case flux can readily be integrated over a surface. By contrast, according to the electromagnetism definition, flux isthe integral over a surface; it makes no sense to integrate a second-definition flux for one would be integrating over a surface twice. Thus, Maxwell's quote only makes sense if "flux" is being used according to the transport definition (and furthermore is a vector field rather than single vector). This is ironic because Maxwell was one of the major developers of what we now call "electric flux" and "magnetic flux" according to the electromagnetism definition. Their names in accordance with the quote (and transport definition) would be "surface integral of electric flux" and "surface integral of magnetic flux", in which case "electric flux" would instead be defined as "electric field" and "magnetic flux" defined as "magnetic field".This implies that Maxwell conceived of these fields as flows/fluxes of some sort.

Given a flux according to the electromagnetism definition, the corresponding flux density, if that term is used, refers to its derivative along the surface that was integrated. By the Fundamental theorem of calculus, the corresponding flux density is a flux according to the transport definition. Given a current such as electric current—charge per time, current density would also be a flux according to the transport definition—charge per time per area. Due to the conflicting definitions of flux, and the interchangeability of flux, flow, and currentin nontechnical English, all of the terms used in this paragraph are sometimes used interchangeably and ambiguously. Concrete fluxes in the rest of this article will be used in accordance to their broad acceptance in the literature, regardless of which definition of flux the term corresponds to.