| Часть цикла статей о |

| математическая константа e |

|---|

|

| Характеристики |

| Приложения |

| Определение e |

| Люди |

| похожие темы |

Число e , также известное как число Эйлера , представляет собой математическую константу, приблизительно равную 2,71828, и ее можно характеризовать по-разному. Это основание из натурального логарифма . [1] [2] [3] Это предел из (1 + 1 / п ) п а п стремится к бесконечности, выражение , которое возникает при изучении сложных процентов . Его также можно вычислить как сумму бесконечного ряда [4] [5]

Это также уникальное положительное число a такое, что график функции y = a x имеет наклон 1 при x = 0 . [6]

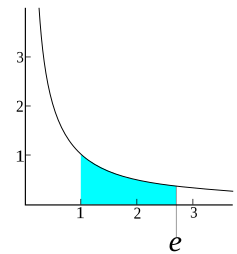

(Естественная) экспоненциальная функция f ( x ) = e x - это единственная функция, которая равна своей производной с начальным значением f (0) = 1 (и, следовательно, можно определить e как f (1) ). Натуральный логарифм или логарифм по основанию e - это функция, обратная натуральной экспоненциальной функции. Натуральный логарифм числа k > 1 может быть определен непосредственно как площадь под кривой y = 1 / x между x = 1 иx = k , и в этом случае e - значение k, для которого эта область равна единице (см. изображение). Существуют различные другие характеристики .

e иногда называют числом Эйлера в честь швейцарского математика Леонарда Эйлера (не путать с γ , константой Эйлера – Маскерони , которую иногда называют просто константой Эйлера ) или константой Напьера . [5] Однако, как говорят , выбор Эйлера символа e был сохранен в его честь. [7] Константа была обнаружена швейцарским математиком Якобом Бернулли при изучении сложных процентов. [8] [9]

Число e имеет огромное значение в математике [10] наряду с 0, 1, π и i . Все пять из этих чисел играют важную и повторяющуюся роль в математике, и эти пять констант появляются в одной формулировке тождества Эйлера . Подобно постоянная П , е является иррациональным (то есть, она не может быть представлена в виде отношения целых чисел) и трансцендентальной (то есть, это не является корень из любых ненулевого многочлена с рациональными коэффициентами). [5] С точностью до 50 знаков после запятой значение e равно:

История [ править ]

Первые упоминания о константе были опубликованы в 1618 году в таблице приложения к работе Джона Напьера по логарифмам . [9] Однако это не содержало самой константы, а просто список логарифмов, вычисленных из константы. Предполагается, что таблица была написана Уильямом Отредом .

Открытие самой константы приписывают Якобу Бернулли в 1683 году [11] [12], который попытался найти значение следующего выражения (которое равно e ):

Первое известное использование константы, представленной буквой b , было в переписке Готфрида Лейбница с Христианом Гюйгенсом в 1690 и 1691 годах. [13] Леонард Эйлер ввел букву e в качестве основы для натуральных логарифмов, написав в письме Кристиану Гольдбах 25 ноября 1731 года. [14] [15] Эйлер начал использовать букву е для обозначения константы в 1727 или 1728 году в неопубликованной статье о силах взрывного действия в пушках, [16] в то время как первое появление е в публикации было в « Механике» Эйлера (1736 г.). [17]Хотя некоторые исследователи использовали букву c в последующие годы, буква e была более распространенной и со временем стала стандартной. [ необходима цитата ]

В математике принято набирать константу курсивом как « е »; ISO 80000-2 : 2009 Стандарт рекомендует наборные константы в вертикальном стиле, но это не было подтверждено научным сообществом. [ необходима цитата ]

Приложения [ править ]

Сложные проценты [ править ]

Якоб Бернулли открыл эту константу в 1683 году, изучая вопрос о сложных процентах: [9]

Счет начинается с $ 1,00 и выплачивается 100% годовых. Если проценты начисляются один раз, в конце года, стоимость счета в конце года составит 2 доллара США. Что произойдет, если проценты начисляются и начисляются чаще в течение года?

Если проценты начисляются дважды в год, процентная ставка за каждые 6 месяцев будет составлять 50%, поэтому начальный 1 доллар умножается на 1,5 дважды, что дает 1,00 доллара × 1,5 2 = 2,25 доллара в конце года. Компаундирования квартальные дает $ 1,00 × 1,25 4 = $ 2,4414 ... и компаундирования ежемесячно дает $ 1,00 × (1 + 1/12) 12 = $ 2,613035 ... Если есть п компаундирования интервалов, интерес для каждого интервала будет 100% / л , и стоимость на конец года составит $ 1,00 × (1 + 1 / n ) n .

Бернулли заметил, что эта последовательность приближается к пределу ( интересующей силе ) с большим n и, следовательно, меньшими интервалами сложения. Еженедельное сложение ( n = 52 ) дает 2,692597 долларов США ..., а ежедневное сложение ( n = 365 ) дает 2,714567 долларов США ... (примерно на два цента больше). Предел увеличения n - это число, которое стало известно как e . То есть при непрерывном начислении сложения стоимость счета достигнет 2,7182818 $ ...

В более общем смысле, счет, который начинается с 1 доллара и предлагает годовую процентную ставку R , через t лет принесет e Rt долларов с непрерывным начислением сложных процентов .

(Note here that R is the decimal equivalent of the rate of interest expressed as a percentage, so for 5% interest, R = 5/100 = 0.05.)

Bernoulli trials[edit]

The number e itself also has applications in probability theory, in a way that is not obviously related to exponential growth. Suppose that a gambler plays a slot machine that pays out with a probability of one in n and plays it n times. Then, for large n, the probability that the gambler will lose every bet is approximately 1/e. For n = 20, this is already approximately 1/2.79.

This is an example of a Bernoulli trial process. Each time the gambler plays the slots, there is a one in n chance of winning. Playing n times is modeled by the binomial distribution, which is closely related to the binomial theorem and Pascal's triangle. The probability of winning k times out of n trials is:

In particular, the probability of winning zero times (k = 0) is

The limit of the above expression, as n tends to infinity, is precisely 1/e.

Standard normal distribution[edit]

The normal distribution with zero mean and unit standard deviation is known as the standard normal distribution, given by the probability density function

The constraint of unit variance (and thus also unit standard deviation) results in the 1/2 in the exponent, and the constraint of unit total area under the curve results in the factor .[proof] This function is symmetric around x = 0, where it attains its maximum value , and has inflection points at x = ±1.

Derangements[edit]

Another application of e, also discovered in part by Jacob Bernoulli along with Pierre Remond de Montmort, is in the problem of derangements, also known as the hat check problem:[18] n guests are invited to a party, and at the door, the guests all check their hats with the butler, who in turn places the hats into n boxes, each labelled with the name of one guest. But the butler has not asked the identities of the guests, and so he puts the hats into boxes selected at random. The problem of de Montmort is to find the probability that none of the hats gets put into the right box. This probability, denoted by , is:

As the number n of guests tends to infinity, pn approaches 1/e. Furthermore, the number of ways the hats can be placed into the boxes so that none of the hats are in the right box is n!/e (rounded to the nearest integer for every positive n).[19]

Optimal planning problems[edit]

A stick of length L is broken into n equal parts. The value of n that maximizes the product of the lengths is then either[20]

- or

The stated result follows because the maximum value of occurs at (Steiner's problem, discussed below). The quantity is a measure of information gleaned from an event occurring with probability , so that essentially the same optimal division appears in optimal planning problems like the secretary problem.

Asymptotics[edit]

The number e occurs naturally in connection with many problems involving asymptotics. An example is Stirling's formula for the asymptotics of the factorial function, in which both the numbers e and π appear:

As a consequence,

In calculus[edit]

The principal motivation for introducing the number e, particularly in calculus, is to perform differential and integral calculus with exponential functions and logarithms.[21] A general exponential function y = ax has a derivative, given by a limit:

The parenthesized limit on the right is independent of the variable x. Its value turns out to be the logarithm of a to base e. Thus, when the value of a is set to e, this limit is equal to 1, and so one arrives at the following simple identity:

Consequently, the exponential function with base e is particularly suited to doing calculus. Choosing e (as opposed to some other number as the base of the exponential function) makes calculations involving the derivatives much simpler.

Another motivation comes from considering the derivative of the base-a logarithm (i.e., loga x),[22] for x > 0:

where the substitution u = h/x was made. The base-a logarithm of e is 1, if a equals e. So symbolically,

The logarithm with this special base is called the natural logarithm, and is denoted as ln; it behaves well under differentiation since there is no undetermined limit to carry through the calculations.

Thus, there are two ways of selecting such special numbers a. One way is to set the derivative of the exponential function ax equal to ax, and solve for a. The other way is to set the derivative of the base a logarithm to 1/x and solve for a. In each case, one arrives at a convenient choice of base for doing calculus. It turns out that these two solutions for a are actually the same: the number e.

Alternative characterizations[edit]

Other characterizations of e are also possible: one is as the limit of a sequence, another is as the sum of an infinite series, and still others rely on integral calculus. So far, the following two (equivalent) properties have been introduced:

- The number e is the unique positive real number such that .

- The number e is the unique positive real number such that .

The following four characterizations can be proven to be equivalent:

- The number e is the limit

Similarly:

- The number e is the sum of the infinite series

- where n! is the factorial of n. (By convention .)

- The number e is the unique positive real number such that

- If f(t) is an exponential function, then the quantity is a constant, sometimes called the time constant (it is the reciprocal of the exponential growth constant or decay constant). The time constant is the time it takes for the exponential function to increase by a factor of e: .

Properties[edit]

Calculus[edit]

As in the motivation, the exponential function ex is important in part because it is the unique nontrivial function that is its own derivative (up to multiplication by a constant):

and therefore its own antiderivative as well:

Inequalities[edit]

The number e is the unique real number such that

for all positive x.[23]

Also, we have the inequality

for all real x, with equality if and only if x = 0. Furthermore, e is the unique base of the exponential for which the inequality ax ≥ x + 1 holds for all x.[24] This is a limiting case of Bernoulli's inequality.

Exponential-like functions[edit]

Steiner's problem asks to find the global maximum for the function

This maximum occurs precisely at x = e.

The value of this maximum is 1.4446 6786 1009 7661 3365... (accurate to 20 decimal places).

For proof, the inequality , from above, evaluated at and simplifying gives . So for all positive x.[25]

Similarly, x = 1/e is where the global minimum occurs for the function

defined for positive x. More generally, for the function

the global maximum for positive x occurs at x = 1/e for any n < 0; and the global minimum occurs at x = e−1/n for any n > 0.

The infinite tetration

- or

converges if and only if e−e ≤ x ≤ e1/e (or approximately between 0.0660 and 1.4447), due to a theorem of Leonhard Euler.[26]

Number theory[edit]

The real number e is irrational. Euler proved this by showing that its simple continued fraction expansion is infinite.[27] (See also Fourier's proof that e is irrational.)

Furthermore, by the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem, e is transcendental, meaning that it is not a solution of any non-constant polynomial equation with rational coefficients. It was the first number to be proved transcendental without having been specifically constructed for this purpose (compare with Liouville number); the proof was given by Charles Hermite in 1873.

It is conjectured that e is normal, meaning that when e is expressed in any base the possible digits in that base are uniformly distributed (occur with equal probability in any sequence of given length).

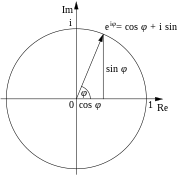

Complex numbers[edit]

The exponential function ex may be written as a Taylor series

Because this series is convergent for every complex value of x, it is commonly used to extend the definition of ex to the complex numbers. This, with the Taylor series for sin and cos x, allows one to derive Euler's formula:

which holds for every complex x. The special case with x = π is Euler's identity:

from which it follows that, in the principal branch of the logarithm,

Furthermore, using the laws for exponentiation,

which is de Moivre's formula.

The expression

is sometimes referred to as cis(x).

The expressions of sin x and cos x in terms of the exponential function can be deduced:

Differential equations[edit]

The family of functions

where C is any real number, is the solution to the differential equation

Representations[edit]

The number e can be represented in a variety of ways: as an infinite series, an infinite product, a continued fraction, or a limit of a sequence. Two of these representations, often used in introductory calculus courses, are the limit

given above, and the series

obtained by evaluating at x = 1 the above power series representation of ex.

Less common is the continued fraction

- [28][29]

which written out looks like

This continued fraction for e converges three times as quickly:[citation needed]

Many other series, sequence, continued fraction, and infinite product representations of e have been proved.

Stochastic representations[edit]

In addition to exact analytical expressions for representation of e, there are stochastic techniques for estimating e. One such approach begins with an infinite sequence of independent random variables X1, X2..., drawn from the uniform distribution on [0, 1]. Let V be the least number n such that the sum of the first n observations exceeds 1:

Then the expected value of V is e: E(V) = e.[30][31]

Known digits[edit]

The number of known digits of e has increased substantially during the last decades. This is due both to the increased performance of computers and to algorithmic improvements.[32][33]

| Date | Decimal digits | Computation performed by |

|---|---|---|

| 1690 | 1 | Jacob Bernoulli[11] |

| 1714 | 13 | Roger Cotes[34] |

| 1748 | 23 | Leonhard Euler[35] |

| 1853 | 137 | William Shanks[36] |

| 1871 | 205 | William Shanks[37] |

| 1884 | 346 | J. Marcus Boorman[38] |

| 1949 | 2,010 | John von Neumann (on the ENIAC) |

| 1961 | 100,265 | Daniel Shanks and John Wrench[39] |

| 1978 | 116,000 | Steve Wozniak on the Apple II[40] |

Since around 2010, the proliferation of modern high-speed desktop computers has made it feasible for most amateurs to compute trillions of digits of e within acceptable amounts of time. It currently has been calculated to 31,415,926,535,897 digits.[41]

In computer culture[edit]

During the emergence of internet culture, individuals and organizations sometimes paid homage to the number e.

In an early example, the computer scientist Donald Knuth let the version numbers of his program Metafont approach e. The versions are 2, 2.7, 2.71, 2.718, and so forth.[42]

In another instance, the IPO filing for Google in 2004, rather than a typical round-number amount of money, the company announced its intention to raise 2,718,281,828 USD, which is e billion dollars rounded to the nearest dollar.

Google was also responsible for a billboard[43]that appeared in the heart of Silicon Valley, and later in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Seattle, Washington; and Austin, Texas. It read "{first 10-digit prime found in consecutive digits of e}.com". The first 10-digit prime in e is 7427466391, which starts at the 99th digit.[44] Solving this problem and visiting the advertised (now defunct) website led to an even more difficult problem to solve, which consisted in finding the fifth term in the sequence 7182818284, 8182845904, 8747135266, 7427466391. It turned out that the sequence consisted of 10-digit numbers found in consecutive digits of e whose digits summed to 49. The fifth term in the sequence is 5966290435, which starts at the 127th digit.[45] Solving this second problem finally led to a Google Labs webpage where the visitor was invited to submit a résumé.[46]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Compendium of Mathematical Symbols". Math Vault. 2020-03-01. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Swokowski, Earl William (1979). Calculus with Analytic Geometry (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-87150-268-1. Extract of page 370

- ^ "e - Euler's number". www.mathsisfun.com. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mathematics 142.D

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric W. "e". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Marsden, Jerrold; Weinstein, Alan (1985). Calculus I (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 319. ISBN 0-387-90974-5.

- ^ Sondow, Jonathan. "e". Wolfram Mathworld. Wolfram Research. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ Pickover, Clifford A. (2009). The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, 250 Milestones in the History of Mathematics (illustrated ed.). Sterling Publishing Company. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4027-5796-9. Extract of page 166

- ^ a b c O'Connor, J J; Robertson, E F. "The number e". MacTutor History of Mathematics.

- ^ Howard Whitley Eves (1969). An Introduction to the History of Mathematics. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-029558-4.

- ^ a b Jacob Bernoulli considered the problem of continuous compounding of interest, which led to a series expression for e. See: Jacob Bernoulli (1690) "Quæstiones nonnullæ de usuris, cum solutione problematis de sorte alearum, propositi in Ephem. Gall. A. 1685" (Some questions about interest, with a solution of a problem about games of chance, proposed in the Journal des Savants (Ephemerides Eruditorum Gallicanæ), in the year (anno) 1685.**), Acta eruditorum, pp. 219–23. On page 222, Bernoulli poses the question: "Alterius naturæ hoc Problema est: Quæritur, si creditor aliquis pecuniæ summam fænori exponat, ea lege, ut singulis momentis pars proportionalis usuræ annuæ sorti annumeretur; quantum ipsi finito anno debeatur?" (This is a problem of another kind: The question is, if some lender were to invest [a] sum of money [at] interest, let it accumulate, so that [at] every moment [it] were to receive [a] proportional part of [its] annual interest; how much would he be owed [at the] end of [the] year?) Bernoulli constructs a power series to calculate the answer, and then writes: " … quæ nostra serie [mathematical expression for a geometric series] &c. major est. … si a=b, debebitur plu quam 2½a & minus quam 3a." ( … which our series [a geometric series] is larger [than]. … if a=b, [the lender] will be owed more than 2½a and less than 3a.) If a=b, the geometric series reduces to the series for a × e, so 2.5 < e < 3. (** The reference is to a problem which Jacob Bernoulli posed and which appears in the Journal des Sçavans of 1685 at the bottom of page 314.)

- ^ Carl Boyer; Uta Merzbach (1991). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 419.

- ^ https://leibniz.uni-goettingen.de/files/pdf/Leibniz-Edition-III-5.pdf, look for example letter nr. 6

- ^ Lettre XV. Euler à Goldbach, dated November 25, 1731 in: P.H. Fuss, ed., Correspondance Mathématique et Physique de Quelques Célèbres Géomètres du XVIIIeme Siècle … (Mathematical and physical correspondence of some famous geometers of the 18th century), vol. 1, (St. Petersburg, Russia: 1843), pp. 56–60, see especially p. 58. From p. 58: " … ( e denotat hic numerum, cujus logarithmus hyperbolicus est = 1), … " ( … (e denotes that number whose hyperbolic [i.e., natural] logarithm is equal to 1) … )

- ^ Remmert, Reinhold (1991). Theory of Complex Functions. Springer-Verlag. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-387-97195-7.

- ^ Euler, Meditatio in experimenta explosione tormentorum nuper instituta.

- ^ Leonhard Euler, Mechanica, sive Motus scientia analytice exposita (St. Petersburg (Petropoli), Russia: Academy of Sciences, 1736), vol. 1, Chapter 2, Corollary 11, paragraph 171, p. 68. From page 68: Erit enim seu ubi e denotat numerum, cuius logarithmus hyperbolicus est 1. (So it [i.e., c, the speed] will be or , where e denotes the number whose hyperbolic [i.e., natural] logarithm is 1.)

- ^ Grinstead, C.M. and Snell, J.L.Introduction to probability theory (published online under the GFDL), p. 85.

- ^ Knuth (1997) The Art of Computer Programming Volume I, Addison-Wesley, p. 183 ISBN 0-201-03801-3.

- ^ Steven Finch (2003). Mathematical constants. Cambridge University Press. p. 14.

- ^ Kline, M. (1998) Calculus: An intuitive and physical approach, section 12.3 "The Derived Functions of Logarithmic Functions.", pp. 337 ff, Courier Dover Publications, 1998, ISBN 0-486-40453-6

- ^ This is the approach taken by Kline (1998).

- ^ Dorrie, Heinrich (1965). 100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics. Dover. pp. 44–48.

- ^ A standard calculus exercise using the mean value theorem; see for example Apostol (1967) Calculus, §6.17.41.

- ^ Dorrie, Heinrich (1965). 100 Great Problems of Elementary Mathematics. Dover. p. 359.

- ^ Euler, L. "De serie Lambertina Plurimisque eius insignibus proprietatibus." Acta Acad. Scient. Petropol. 2, 29–51, 1783. Reprinted in Euler, L. Opera Omnia, Series Prima, Vol. 6: Commentationes Algebraicae. Leipzig, Germany: Teubner, pp. 350–369, 1921. (facsimile)

- ^ Sandifer, Ed (Feb 2006). "How Euler Did It: Who proved e is Irrational?" (PDF). MAA Online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ^ Hofstadter, D.R., "Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought" Basic Books (1995) ISBN 0-7139-9155-0

- ^ (sequence A003417 in the OEIS)

- ^ Russell, K.G. (1991) Estimating the Value of e by Simulation The American Statistician, Vol. 45, No. 1. (Feb., 1991), pp. 66–68.

- ^ Dinov, ID (2007) Estimating e using SOCR simulation, SOCR Hands-on Activities (retrieved December 26, 2007).

- ^ Sebah, P. and Gourdon, X.; The constant e and its computation

- ^ Gourdon, X.; Reported large computations with PiFast

- ^ Roger Cotes (1714) "Logometria," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 29 (338) : 5–45; see especially the bottom of page 10. From page 10: "Porro eadem ratio est inter 2,718281828459 &c et 1, … " (Furthermore, by the same means, the ratio is between 2.718281828459… and 1, … )

- ^ Leonhard Euler, Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum (Lausanne, Switzerland: Marc Michel Bousquet & Co., 1748), volume 1, page 90.

- ^ William Shanks, Contributions to Mathematics, ... (London, England: G. Bell, 1853), page 89.

- ^ William Shanks (1871) "On the numerical values of e, loge 2, loge 3, loge 5, and loge 10, also on the numerical value of M the modulus of the common system of logarithms, all to 205 decimals," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 20 : 27–29.

- ^ J. Marcus Boorman (October 1884) "Computation of the Naperian base," Mathematical Magazine, 1 (12) : 204–205.

- ^ Daniel Shanks and John W Wrench (1962). "Calculation of Pi to 100,000 Decimals" (PDF). Mathematics of Computation. 16 (77): 76–99 (78). doi:10.2307/2003813. JSTOR 2003813.

We have computed e on a 7090 to 100,265D by the obvious program

- ^ Wozniak, Steve (June 1981). "The Impossible Dream: Computing e to 116,000 Places with a Personal Computer". BYTE. p. 392. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Alexander Yee. "e".

- ^ Knuth, Donald (1990-10-03). "The Future of TeX and Metafont" (PDF). TeX Mag. 5 (1): 145. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- ^ "First 10-digit prime found in consecutive digits of e". Brain Tags. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ^ Kazmierczak, Marcus (2004-07-29). "Google Billboard". mkaz.com. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

- ^ The first 10-digit prime in e. Explore Portland Community. Retrieved on 2020-12-09.

- ^ Shea, Andrea. "Google Entices Job-Searchers with Math Puzzle". NPR. Retrieved 2007-06-09.

Further reading[edit]

- Maor, Eli; e: The Story of a Number, ISBN 0-691-05854-7

- Commentary on Endnote 10 of the book Prime Obsession for another stochastic representation

- McCartin, Brian J. (2006). "e: The Master of All" (PDF). The Mathematical Intelligencer. 28 (2): 10–21. doi:10.1007/bf02987150.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to E (mathematical constant). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: E (mathematical constant) |

- The number e to 1 million places and 2 and 5 million places

- e Approximations – Wolfram MathWorld

- Earliest Uses of Symbols for Constants Jan. 13, 2008

- "The story of e", by Robin Wilson at Gresham College, 28 February 2007 (available for audio and video download)

- e Search Engine 2 billion searchable digits of e, π and √2

![{\displaystyle e=\lim _{n\to \infty }{\frac {n}{\sqrt[{n}]{n!}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ce0cd8eb0003d22f6e68f69c95cf434c43bebc58)

![{\displaystyle e=[2;1,2,1,1,4,1,1,6,1,...,1,2n,1,...],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/eda10aefcc9d9e0268fb3b0734147f652800e6ac)